Meteor Shower Spawned by Halley's Comet Peaks Early Saturday

Early bird skywatchers set your alarms: The annual October meteor shower will peak before sunrise on Saturday (Oct. 22) as the Earth passes through a stream of leftover dust from the famous Halley's Comet.

The Orionid meteor shower promises to offer skywatchers with a dark sky and good weather up to 15 meteors per hour at its peak, according to a NASA forecast.

"Although this isn't the biggest meteor shower of the year, it's definitely worth waking up for," said Bill Cooke, head of the NASA Meteoroid Environment Office, in a statement. "The setting is dynamite."

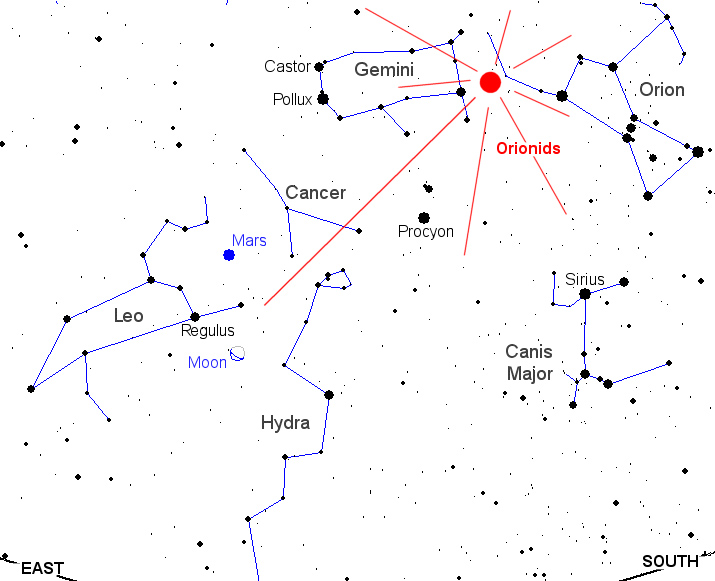

The Orionids will emanate from a point in the southeastern sky (as viewed from the northern mid-latitudes) near the raised arm of Orion the Hunter, the constellation that gives them their name. From there, they streak across Taurus the Bull, the twins of Gemini, Leo the Lion, and Canis Major.

The sky map of the Orionid meteor shower here shows where to look to see the "shooting star" display.

The Orionids are visible each year, even though Halley's comet only swings by about every 75 years. This is because comets leave a trail of volatile ices and dust along their orbital path that hangs around long after the comets have come and gone.

This year, some of the Orionids will also appear to pass through a "celestial triangle" formed by the crescent moon, Mars and Regulus, a star in the constellation Leo. Others may even collide with the moon, and Cooke says this presents a great opportunity for amateur skywatchers and scientists alike.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Unlike Earth, the moon has no atmosphere to intercept and burn up meteoroids, so pieces of debris reach the surface and explode where they hit.

"Some explode with energies exceeding hundreds of pounds of TNT," Cooke said. These lunar crashes could produce flashes so bright they can sometimes be seen through backyard telescopes.

By observing these collisions, Cooke and his colleagues are able to learn about the structure of comet debris streams and the energy of the particles within them. Since the start of their monitoring program in 2005, they've seen 15 Orionids hit the moon: two in 2007, four in 2008, and nine in 2009, Cooke said.

This year looks promising as one-quarter of the moon's dark terrain will be exposed to Halley's debris stream, so the team has millions of square miles to scan for explosions, he added.

As Halley swings in a huge orbital loop around the sun, it passes near the plane of Earth's orbit in two places (the first as it swings inward to the inner solar system, the other as it leaves). The gas and dust shed by the comet, therefore, is encountered by Earth twice a year.

Earth passes through the first patch of comet Halley debris in early May, giving rise to the annual Eta Aquarid meteor shower. The pass the second pass occurs every year in late October, giving rise to the Orionids.

Editor's note: If you snap a great photo of the Orionid meteor shower and would like to share the image and your comments for a possible image gallery or story, please contact managing editor Tariq Malik at tmalik@space.com.

Natalie Wolchover (@nattyover) is a staff writer for Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site to SPACE.com. For the latest in space science and exploration news, follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science and a contributor to Space.com from 2010 to 2012. She is now a senior writer and editor at Quanta Magazine, where she specializes in the physical sciences. Her writing has appeared in publications including Popular Science and Nature and has been included in The Best American Science and Nature Writing. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley.