How Russian Spacecraft Crash Affects Space Station & Crew

Today's crash of a Russian cargo ship may force NASA to rethink some of its plans for the International Space Station, but the mishap shouldn't leave the orbiting lab or its six-astronaut crew high and dry, agency officials said.

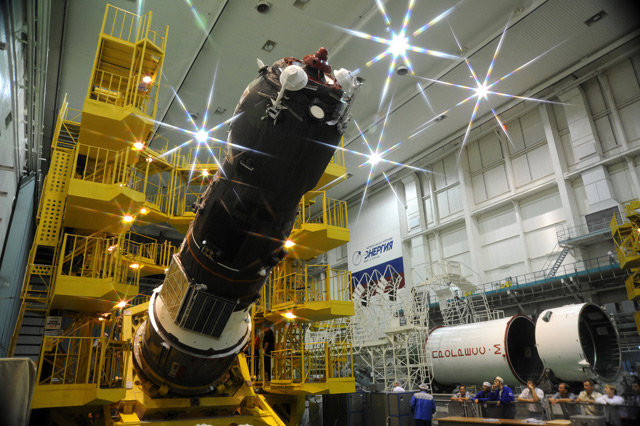

The unmanned Russian Progress 44 vehicle crashed this morning (Aug. 24) after suffering an anomaly about five minutes into its flight. The cargo ship was carrying 2.9 tons of food, fuel and supplies to the space station.

However, these things weren't absolutely critical to the immediate day-to-day operation of the orbiting lab, NASA officials said.

"There were very few one-of-a-kind items — in fact, none that I'm aware of," Mike Suffredini, NASA's program manager for the International Space Station, told reporters today. "Logistically, we're in very good shape."

Station should be OK for a while

The anomaly was apparently caused by a problem with the Progress' Soyuz-U rocket, NASA officials said. Russian engineers are working hard to figure out exactly what went wrong. Video of the Progress launch shows what appeared to be an on-time liftoff into a clear, blue sky.

Two more Progress resupply missions are scheduled for this year. It's too early to tell whether the problem will be identified and fixed in time to go ahead with those launches, Suffredini said. But, he added, it wouldn't be a disaster if Progress vehicles were grounded for a while.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A European cargo ship known as ATV-3 is slated to launch on March 5 of next year and dock with the station two weeks later. The orbiting lab easily has enough supplies to last until then, Suffredini said. [Vote Now! The Best Spaceships of All Time]

"If we had to wait all the way until ATV-3 was ready to go fly, I don't have any concern that we couldn't support the crew to that period," Suffredini said.

Skeleton crew possible

The Progress' Soyuz-U booster is similar to the Soyuz-FG rocket that launches astronauts toward the space station. Until American private companies get their own spaceships up and flying, NASA is relying on the Soyuz to provide this taxi service.

No astronauts are likely to launch on a Soyuz-FG until the causes of Wednesday's crash are pinpointed and fixed. And that could force some rejiggering of crew numbers on the space station, at least in the near term. [How Russia's Progress Spaceships Work (Infographic]

A Soyuz is set to launch on Sept. 21, for example, to deliver three new astronauts to the orbiting lab, replacing three current station astronauts who are scheduled to come home at about the same time.

If no Soyuz are ready to launch for a lengthy stretch, the station may have to make do with a skeleton crew for a while. The three crewmembers will have to come home relatively soon, after all; NASA generally doesn't want its astronauts to spend more than six or seven months aboard the station during any one stint because of concerns about radiation exposure and the long-term effects of microgravity.

The three spaceflyers scheduled to come home next month— American Ron Garan and Russians Andrey Borisenko and Alexander Samokutyaev — arrived at the orbiting lab on April 6.

And the astronauts' Soyuz return ships are only rated for about six months in space, so they'll have to come back soon, too. (Astronauts are not dependent on incoming Soyuz to come home; two Soyuz are docked to the station at the moment to take crewmembers back to Earth, and to serve as "lifeboats" in the event of an emergency.)

A crew of three could operate the station just fine, Suffredini said, though they wouldn't be able to do nearly as much science work. And a short-staffed station would require even fewer supplies, meaning it could probably last even beyond the March 5 ATV-3 resupply mission if need be.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.