The Greatest Mysteries of Mars

Each week this summer, Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site to SPACE.com presents The Greatest Mysteries of the Cosmos, starting with our solar system.

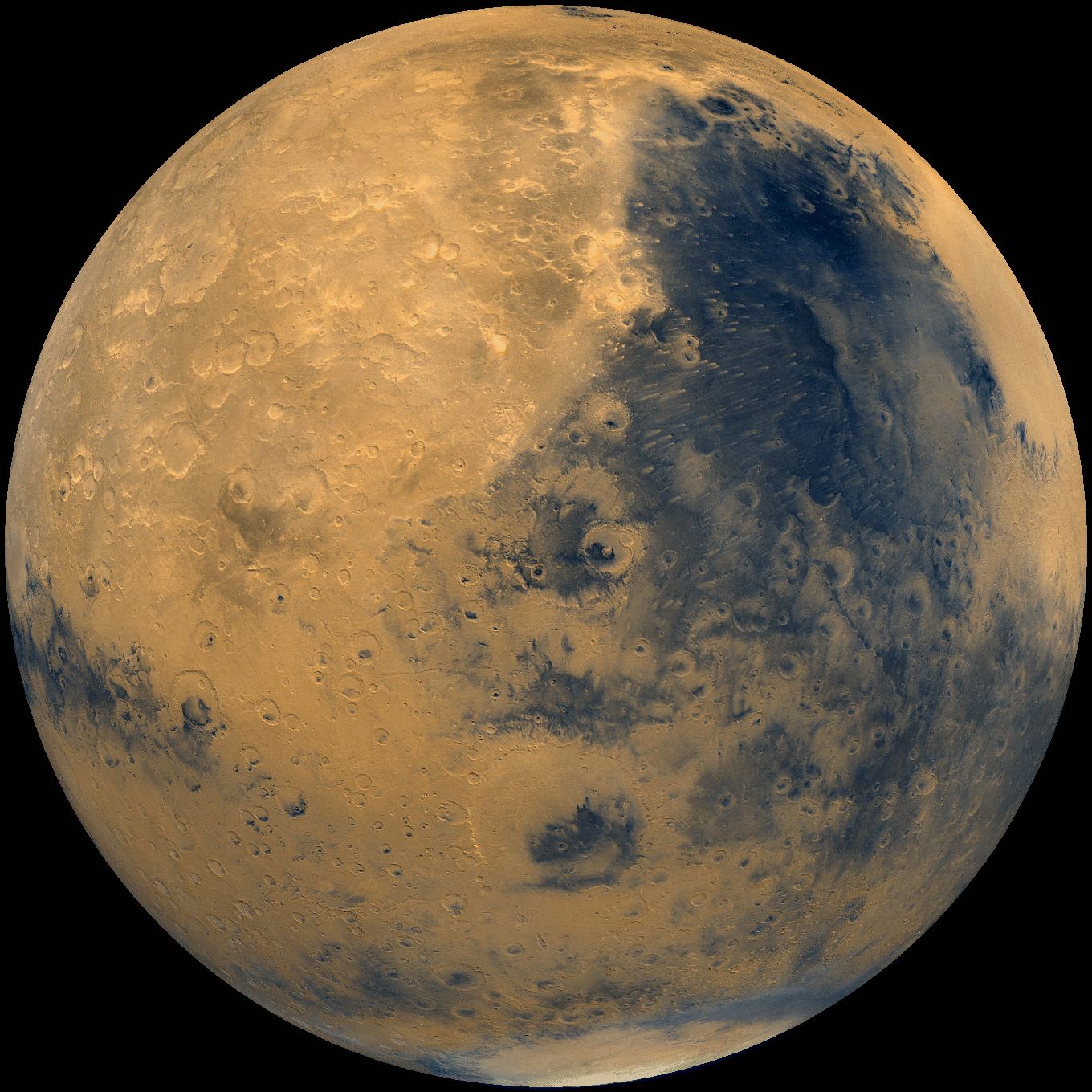

Mars, the fourth planet from the sun, gets its name from the Roman god of war on account of its blood-rust color. From an exploratory point of view, the moniker is fitting: Mars has fought off most of our scientific advances. Over half of the more than 40 spacecraft sent to study the Red Planet have failed; some have been lost in space and others have crashed onto the planet's surface.

Despite these setbacks, our curiosity regarding Mars has never abated. Several missions are in the works — one in fact involving a rover named Curiosity. [Vote! Where NASA's Next Mars Rover Land]

Scientists hope the new missions will help answer the major mysteries about this world, which include:

Abode of life?

You can't talk about Mars without raising the question of life. The Red Planet beckons because many scientists consider it the likeliest place in our solar system for extraterrestrial life to have once developed – or even still persist.

"What everyone wants to know is: has the planet ever harbored life?" said Steve Squyres, a professor of astronomy at Cornell University. Squyres is the principle investigator for the Mars Exploration Rover mission that put the rovers Spirit and Opportunity on the Red Planet in early 2004. (Spirit stopped working last year, but Opportunity is still chugging along.)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Today, and for most of its history, Mars has been a "cold, dry, desolate world," Squyres told Life's Little Mysteries. But multiple lines of evidence point to Mars as having been warm, wet and far more Earthlike about four billion years ago, early in its planethood. [Will We Really Find Alien Life in 20 Years?]

To make life, you (most likely) need water. And guess what? Signs point to Mars once being absolutely drenched. Minerals on the surface, such as sulfates and clays, could have formed only in the presence of water.

Many geologic features suggest great torrents of the stuff flowing overland. A huge amount of water still exists on Mars, but it is frozen away in the polar ice caps, as permafrost and in recently discovered, giant underground glaciers.

Hints of Martian microbial life have come in many guises: a contested Viking lander experiment in the 1970s; a famous "Martian meteorite," recovered in Antarctica with odd structures that some researchers construe as tiny fossils preserved before the rock was blasted off of Mars; and whiffs of methane in the thin atmosphere that could have a biological origin.

Warm and wet to cold and dry

The next biggest mystery concerning Mars is, "What happened?" as Squyres put it.

"Mars was a warm, wet interesting place for just 500 million to one billion years," Squyres said, "and then the fun was over."

Future Mars exploration missions will carry more sensitive equipment to help answer the interrelated questions about life and the stark change in conditions on the Red Planet.

NASA's Mars Science Laboratory and its car-sized, six-wheeled rover Curiosity will land next summer and begin analyzing rocks and sending pictures back to Earth for study. In addition, the European Space Agency has its first rover, ExoMars, gearing up for a 2018 launch. A sample return mission of Martian soil and rocks has long been considered but is not yet scheduled, Squyres said. [How Much Would You Weigh on Mars?]

Bit by bit, scientists hope to piece together whether Mars ever had a thicker atmosphere, as well as how geologic activity and volcanism have influenced the world over the eons. After all, Mars is home to the Valles Marineris, one of the longest canyon systems known, and Olympus Mons, the biggest volcano in the solar system.

A tale of two hemispheres

Mars is very different from north to south: Smooth, younger lightly cratered lowlands predominate in the north, while ancient, heavily cratered highlands characterize the southern hemisphere. The northern hemisphere is also on average 3 miles (5 kilometers) lower than the south. What gives?

The best bet for this so-called hemispheric dichotomy is a giant impact to the north from a Pluto-sized body four billion years ago or so. If the theory, which Squyres proposed in 1984, is correct, it would mean that the northern 40 percent of Mars is actually an impact crater. That would give the Red Planet another geological superlative — for having the largest impact crater in the solar system.

Bonus boggler: Funky, lumpy moons

Mars has two small, potato-shaped moons called Phobos and Deimos.

In many respects, including size, shape, color and apparent composition, the moons look to be wayward asteroids captured by Mars' gravity. But the fact that Phobos and Deimos have circular orbits above Mars' equator challenges this capture concept.

Two asteroids flying past would be unlikely to both have such a trajectory, and subsequent history after capture, to settle them into such an orbital arrangement. "How [Phobos and Deimos] really got there is hard to say," Squyres said.

Instead, the moons could have formed from material blasted out of Mars by an impact, just like our moon, and retained a lumpy, uneven shape because they lack the mass and corresponding gravity to become spherical.

At any rate, the speculation in the 1950s and 1960s that Phobos and Deimos might be artificial in nature has long been debunked, along with all the other wild sci-fi rumors about irrigation "canals," human faces carved in rocks and little green men with ray guns.

This story was provided by Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site to SPACE.com. Follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter @llmysteries, then join us on Facebook.

Adam Hadhazy is a contributing writer for Live Science and Space.com. He often writes about physics, psychology, animal behavior and story topics in general that explore the blurring line between today's science fiction and tomorrow's science fact. Adam has a Master of Arts degree from the Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute at New York University and a Bachelor of Arts degree from Boston College. When not squeezing in reruns of Star Trek, Adam likes hurling a Frisbee or dining on spicy food. You can check out more of his work at www.adamhadhazy.com.