Giant Black Holes May Be Smaller Than Previously Thought

This story was updated at 6:38 p.m. EST.

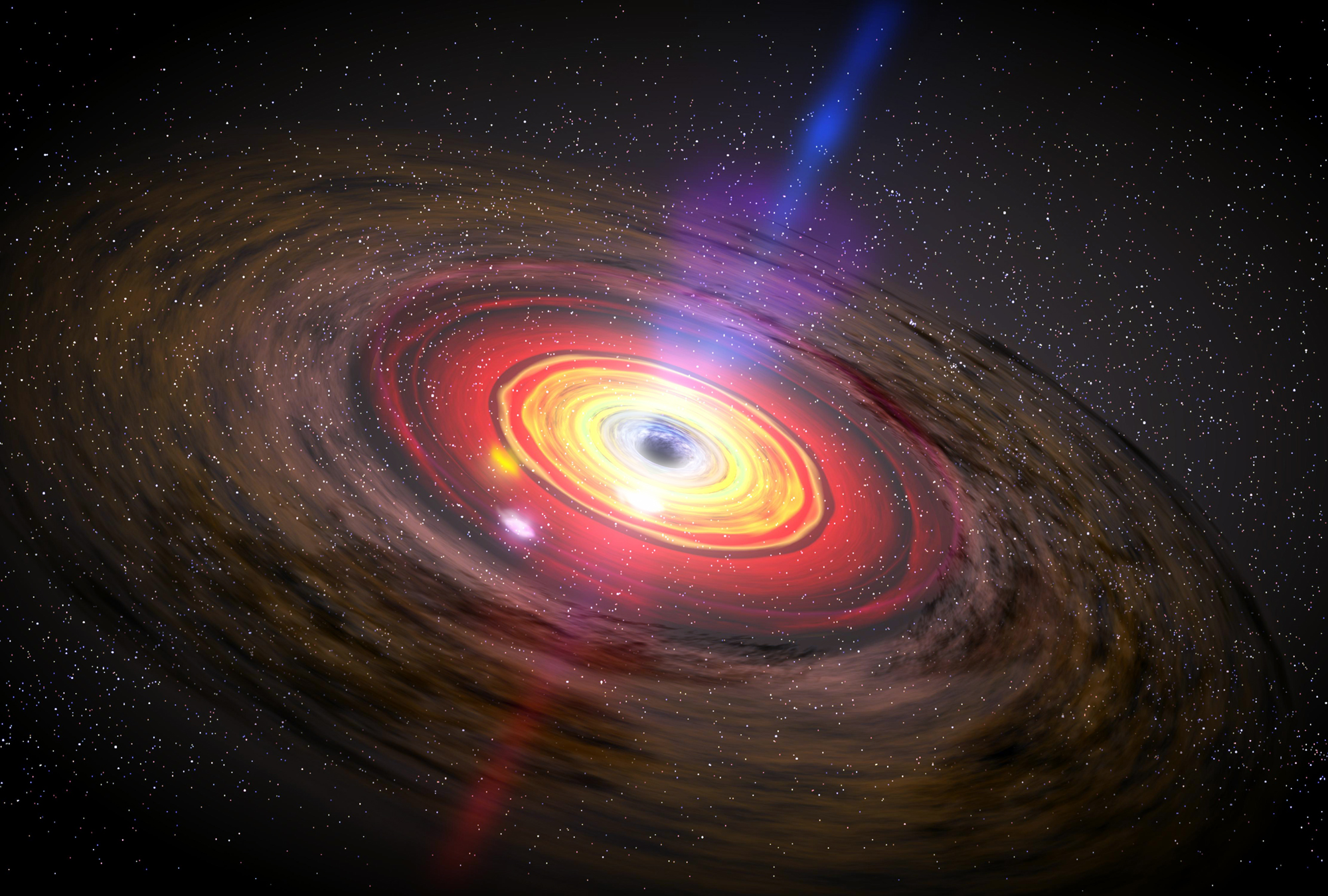

The mysterious zones of destruction surrounding the gargantuan black holes suspected to lurk at the heart of most galaxies are now giving up some of their secrets, thanks to a novel way of investigating these violent enigmas.

These new findings revealed these giant black holes may be smaller than scientists previously thought, which could help solve questions regarding how they grew.

The centers of nearly all galaxies are suspected to harbor supermassive black holes that are millions to billions the mass of our own sun. These monsters are surrounded by extremely bright zones assumed to hold super-hot matter rushing around — and into — the black holes.

However, the central regions of these galaxies are typically relatively small, too much so to see clearly. Their small size has left their structure and behavior largely a mystery in spite of decades of intense study.

Black hole hearts of galaxies

To learn more about these zones, astrophysicists Wolfram Kollatschny and Matthias Zetzl at the University of Gottingen in Germany looked more closely at the light emerging from them.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Light comes in a wide variety of wavelengths — some visible and many invisible. The wavelengths of light that matter emits often come in specific clumps or lines, which can reveal much about the composition or activity of the material in question.

The researchers analyzed the light from 37 galaxies and discovered a consistent variation in how broad several emission lines were. This enabled the researchers to infer the speed at which the gas in these central regions orbits the black holes, as well as turbulence within this gas.

The diameter of a black hole depends on its mass. When it comes to a super-massive black hole such as the one at the center of the Milky Way galaxy, which has a mass of about 4 million suns, scientists estimate its diameter at about 93 million miles (150 million km), or roughly the distance between the sun and the Earth.

Weighing black holes

From the speed at which this matter orbits and its distance from the black hole, the researchers deduced the masses of these giant black holes using Kepler's centuries-old laws of motion.

Intriguingly, they found the masses of these black holes seem to be two to 10 times smaller than previous estimates. The question of how galaxies might have grown such giant black holes has long been a vexing one for scientists.

"The evolution of these central regions is important for our general understanding of galactic evolution," Kollatschny told SPACE.com.

The scientists detailed their findings in the Feb. 17 issue of the journal Nature.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us