Redshirts Aren't Likeliest to Die — and Other 'Star Trek' Math Lessons

NEW YORK — The original "Star Trek" series isn't just a milestone of science fiction, it's also a treasure trove of mathematical ideas — as Space.com discovered when we attended "Star Trek: The Math of Khan" at the Museum of Mathematics on Thursday (April 6). Tribbles, inevitable aliens and computer-breaking paradoxes all made appearances at the talk — along with the fate of those (evidently) not-so-ill-fated red-shirted crew.

Connor Trinneer, who played Commander Trip Tucker on "Star Trek: Enterprise," introduced the talk, which was sponsored by the Simons Foundation. Then the guest of honor, James Grime, set the scene before launching into his math explanations.

"'Star Trek' is very famous today, and it predicted a lot of technology and included a lot of science fiction ideas: futuristic technology such as warp speed, going faster than light, transporters that teleport you from one place to another and green alien space babes," Grime said. "And all of those things have been discussed in great detail in the past by scientists, by nerds — especially the green alien space babes — to which I say, Boring!" [How 'Star Trek' Technology Works (Infographic)]

"'Star Trek' is a science fiction show, but there's no such thing as maths fiction," he added. "Surely, any maths that appears in the show should be on firmer ground, right?"

Here are some of the many mathematical tidbits Space.com gleaned from the lecture.

Good to be a 'redshirt'

Grime first focused on an age-old assertion: that crewmembers wearing red shirts in the original "Star Trek" series, which denote working in engineering or security, are far more likely to be killed off than any other shirt color.

That claim, in fact, is false — more "redshirts" died on-screen than any other crew type (10 gold-shirted, which are command personnel; eight blue-shirted, who are scientists; and 25 red-shirted, Grime said), but that calculation fails to take into account that there are far more redshirts on the ship to start with than any other crew type.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In other words, we're looking at the probability that you are a redshirt if you die (58 percent) — what we want to know is the probability that you die if you're a redshirt, Grime said.

Grime used the "Star Trek" technical manual to find out how many of each crew type there were, which painted a different picture: out of 239 redshirts, 25 died, which is 10 percent. Out of 55 goldshirts, 10 died, which is 18 percent! So you are more likely to die as a goldshirt, Grime said.

"There is some truth in the old 'Star Trek' myth if you look at security officers … 20 percent of security officers died," Grime added. "So I think the moral of the story is, if you're on the starship Enterprise and you want to survive, be a scientist." (Only 6 percent of the blue-shirted scientists died over the course of the show.)

Vulcans are like cicadas

Grime also compared the Vulcans' mode of reproduction, which happens only once every seven years, to that of tribbles, whose numbers grow exponentially and reach great numbers very quickly. For instance, in "The Trouble with Tribbles," Spock calculates that after just three days there will be 1,771,561 tribbles! Because each tribble produces 10 additional tribbles every 12 hours, and the original tribble sticks around to reproduce more, the generations grow by 1+10 = 11 times each generation — giving 1 x 11^6 tribbles after six generations (three days).

The Vulcan pattern is like that of certain types of cicadas, who live underground and come out only one spring every several years, which lets them avoid predators — in fact, the mating cycles of those so-called periodical cicadas are prime numbers, like 13 or 17 years, which means that they can avoid overlapping with predators that emerge on regularly spaced periodical cycles, too. For instance, if a predator emerged every four years it'd be able to take out prey who emerged every multiple of four — four, eight, 12 and so on. If the prey waited just one extra year, coming out every five, the predator and prey would only overlap every 20 years. Hence, numbers of years with few factors are the way to go for cicadas — and maybe for Vulcans, too. [What I Learned by Watching Every 'Star Trek' Show and Movie]

Computer-breaking paradox

According to Grime, Captain Kirk talks computers to death no fewer than four separate occasions in the original series. The captain often achieves this feat using sentences similar to the "Liar's Paradox": "This sentence is false." It's a paradox because if the sentence is false, then the sentence is stating the truth, even though it is supposed to be false; if the sentence is true, then it must be true that the sentence is false.

A similar statement powers mathematician Kurt Gödel's Incompleteness Theorem, which in effect proves there's a similarly paradoxical statement like "This statement is not provable" in any given mathematical system, Grime said. If the statement is true, it means there are true mathematical statements that can never be proved, like "holes" in mathematics. If the statement is false, it’s a contradiction, and that means there are contradictions within a mathematical system — so any system without any contradictions will also have statements that are impossible to prove. So something very much like Kirk's computer-busting paradox is something that appears in real mathematics.

Chasing a similar question, the mathematician and pioneering scientist Alan Turing set out to find out whether it's possible to determine whether any given computer program will be able to solve a problem and halt or get stuck working on the problem forever. Ultimately, he proved that you cannot write another program to predict whether a program will finish or not — a result that suggests that you can't definitively determine whether a statement will ever be possible to prove, Grime said.

"When you see in science fiction a computer being defeated by the use of a paradox, that's because that idea goes back to the original paper where the computer was designed, when it was theorized by Alan Turing — it goes back to the original paper itself," Grime said. So the incompleteness of mathematics, and the inability to solve the so-called "halting problem," is all for the best as far as android-dodging Starfleet crew are concerned.

Who is out there?

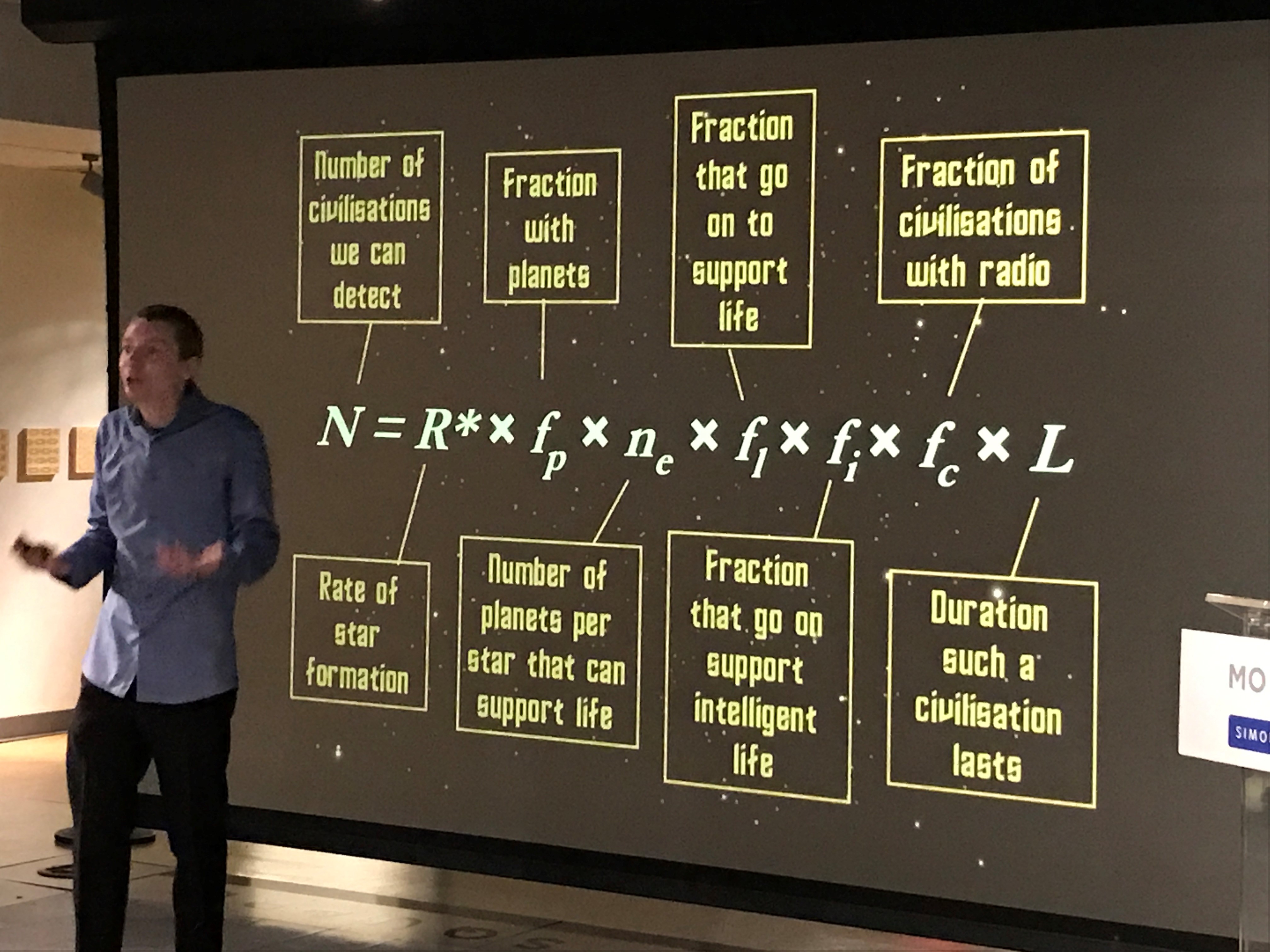

Grime also talked about the Drake equation, which estimates the chances of encountering communications from an intelligent extraterrestrial civilization. Frank Drake takes into account the number of galaxies whose emissions are detectable from Earth, how easily life develops and becomes capable of communication and how many places throughout the universe are suitable for life, among other variables. Most of those variables aren't knowable yet, but plugging numbers in offers a potentially inspiring glimpse into just how common extraterrestrial life could be — originally, Drake and colleagues concluded there would be between 1,000 and 100,000,000 civilizations we could potentially detect.

It certainly inspired "Star Trek" creator Gene Roddenberry, Grime said — he used it in his pitch for the show to justify the many alien species Kirk and crew encounter over the course of the show. Or at least he tried to use it — he made up his own, nonsensical formula, which came to be known as "Roddenberry's formula."

Trinneer, the "Star Trek: Enterprise" actor who introduced the talk, chatted with Space.com afterward about the likelihood of alien life existing somewhere in the universe. He said he wondered about the distance to our nearest alien neighbors, which he assured were very likely to exist.

"It would be wanton hubris to believe that it's not the case," he said.

"Star Trek: The Math of Khan" will be available to watch online soon, and Space.com will certainly let you know when the time comes.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.