Incredible Technology: How to Find Dangerous Asteroids

Editor's Note: In this weekly series, SPACE.com explores how technology drives space exploration and discovery.

Searching for potentially Earth-destroying asteroids today isn't easy.

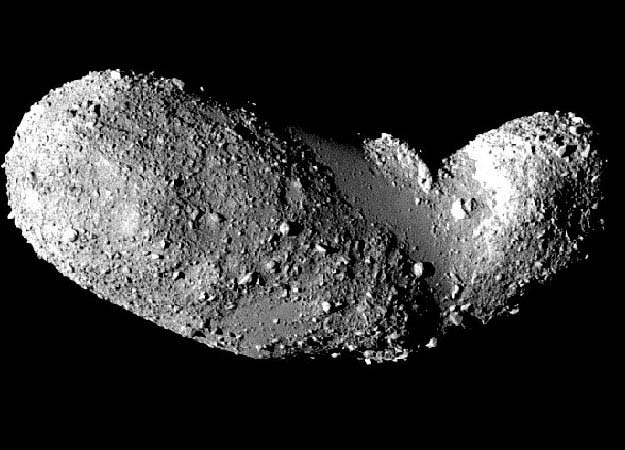

They're dark, difficult to see from the surface of the planet, and there are a lot of them floating in the solar system. Scientists are now looking into new, higher-tech ways to find and track near-Earth objects, but for now, much of the hard work of asteroid tracking is done the old-fashioned way: with a telescope on a clear night.

NASA scientists, astronomers around the world and amateur observers with backyard telescopes devote their lives and free time to seeking out potentially hazardous near-Earth objects (NEOs). [Photos: Potentially Dangerous Asteroids]

"It all begins with an observer making observations," Gareth Williams, of the Minor Planet Center, the clearinghouse for asteroid and other minor-planet documentation, told SPACE.com "They can be observing known objects, or they can be searching for new objects, but even if they're searching for known objects — just to take a pretty picture or some reason — new objects can come into the field. About one in 1,000 of these new objects turn out to be an object that's moving anomalously when compared to other objects in the frame."

Hunting asteroids

Anomalous motion — when an object moves in a different way than other bodies in a frame — can signal something to a keen observer. The skywatcher then reports his or her findings to the Minor Planet Center (MPC), located in Cambridge, Mass., and officials with the MPC search the organization's database to try to find a match with known, already-tracked objects.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

If the new observation doesn't match any known object, the MPC puts it onto the NEO confirmation page — a database where observers can find information about asteroids with orbits that have not been sufficiently traced.

The MPC functions as the central database for all information about NEOs. The astronomers of the MPC — run by the International Astronomical Union — collect and help verify all of the space-rock sightings that are reported.

An interconnected group of observers and sky surveys work to validate claims of near-Earth-object sightings on a daily basis. This month alone, observers have discovered 80 NEOs out of 656,546 observations.

So far, observers around the world have found and tracked more than 10,000 near-Earth objects. Astronomers have found more than 90 percent of the possibly "world-ending" cosmic objects that could threaten Earth, but tracking anything smaller than 0.6 miles (1 kilometer) across is more difficult.

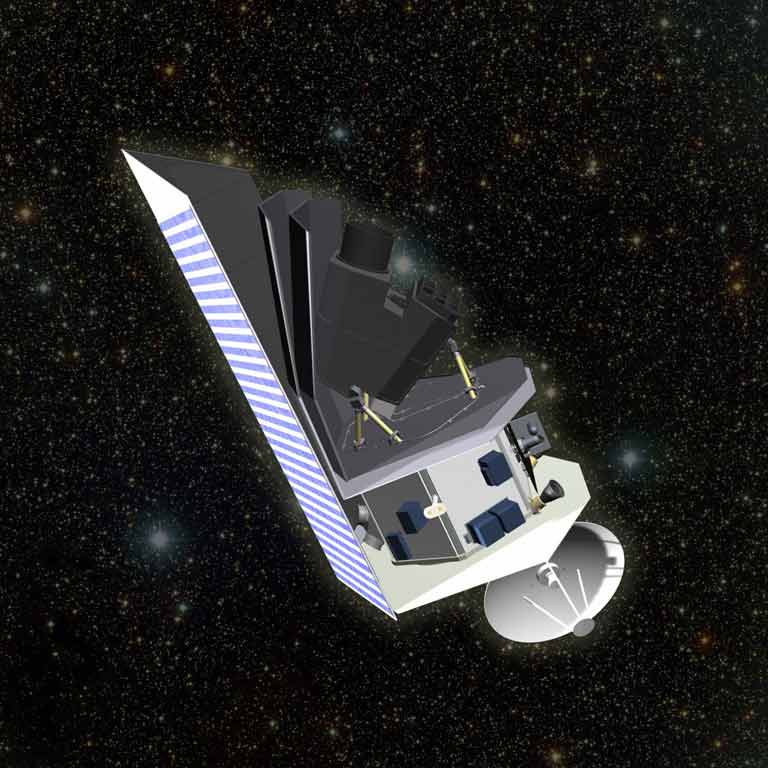

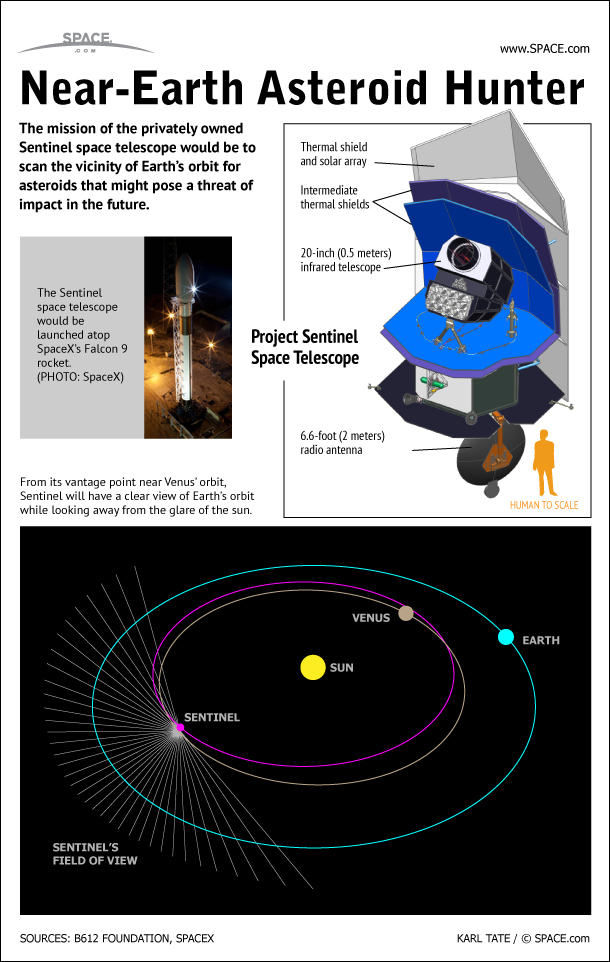

"NASA has not even come close to finding and tracking the 1 million smaller asteroids that might only just wipe out a city, or perhaps collapse the world economy if they hit in the wrong place," Ed Lu, CEO of the B612 Foundation, a nonprofit working to build Sentinel asteroid observatory, a NEO-hunting space telescope, said in April.

In all, less than 10 percent of asteroids measuring about 459 feet (140 meters) across have been found, whereas about 1 percent of asteroids measuring 131 feet (40 m) in diameter have been tracked. While an impact caused by these relatively small space rocks wouldn't cause a worldwide disaster, they could induce some regional issues.

The Sentinel space telescope is designed to hunt for these small potentially city-destroying objects. The spacecraft would scan the solar system in infrared light, making dark asteroids easier to see.

Finding near-Earth objects could also make it easier for asteroid mining companies and NASA engineers to devise strategies to launch future manned or unmanned missions to NEOs.

Earth occasionally captures a cosmic object in its gravity, creating a transitory "minimoon" before the space rock zips off to another part of the solar system. The tiny asteroids, usually only about 3 feet (1 m) in diameter, can get caught in the planet's orbit for about a year, possibly allowing scientists to launch a mission aimed at investigating (or even mining) the space rock.

NASA is planning a bold asteroid-capture mission to retrieve a roughly 25-foot-wide (7.6 m) asteroid and pull it into lunar orbit. Astronauts could then investigate the space rock using the space agency's Space Launch System rocket and Orion capsule.

Follow Miriam Kramer @mirikramer and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.