The newfound Comet ISON has the potential to be one of the brightest ever seen when it streaks through the inner solar system this November, but whether it will live up to the hype is anybody's guess.

Astronomers have a tough time forecasting the brightness of incoming comets. Ballyhooed "comet of the century" candidates sometimes fizzle out, as Kahoutek did in 1973, while some icy wanderers put on a surprisingly good show for skywatchers.

Why is it so difficult to predict comet behavior? For starters, comets are like snowflakes — no two are alike.

Dirty snowballs

While comets have been called “dirty snowballs,” recent observations by unmanned space probes suggest that they may not be too different from asteroids on the outside. Comets appear to have rocky surfaces which in most cases are probably not much more than several miles across. [Amazing Comet Photos of 2013]

What makes them much different from asteroids, however, is that frozen reservoirs icy material are hidden beneath the crust or contained in fissures and craters that pockmark the surface.

Such comet "snow" is composed of ordinary water ice plus frozen ammonia and some other more exotic compounds, with dust grains of different sizes and compositions mixed in. These pools of volatile materials are called “active regions.”

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Because comets spend most of their time far out in space, billions of miles from the sun, the nucleus is completely stable, since it’s in a state of deep freeze where temperatures barely hover above absolute zero (minus 460 degrees Fahrenheit, or minus 273 degrees Celsius).

When a comet nears the sun, its frozen gases react to the increasing heat by vaporizing and expanding into a huge tenuous cloud around the nucleus called the coma. The nucleus and the coma make up the head of the comet, which may swell to more than 100,000 miles across.

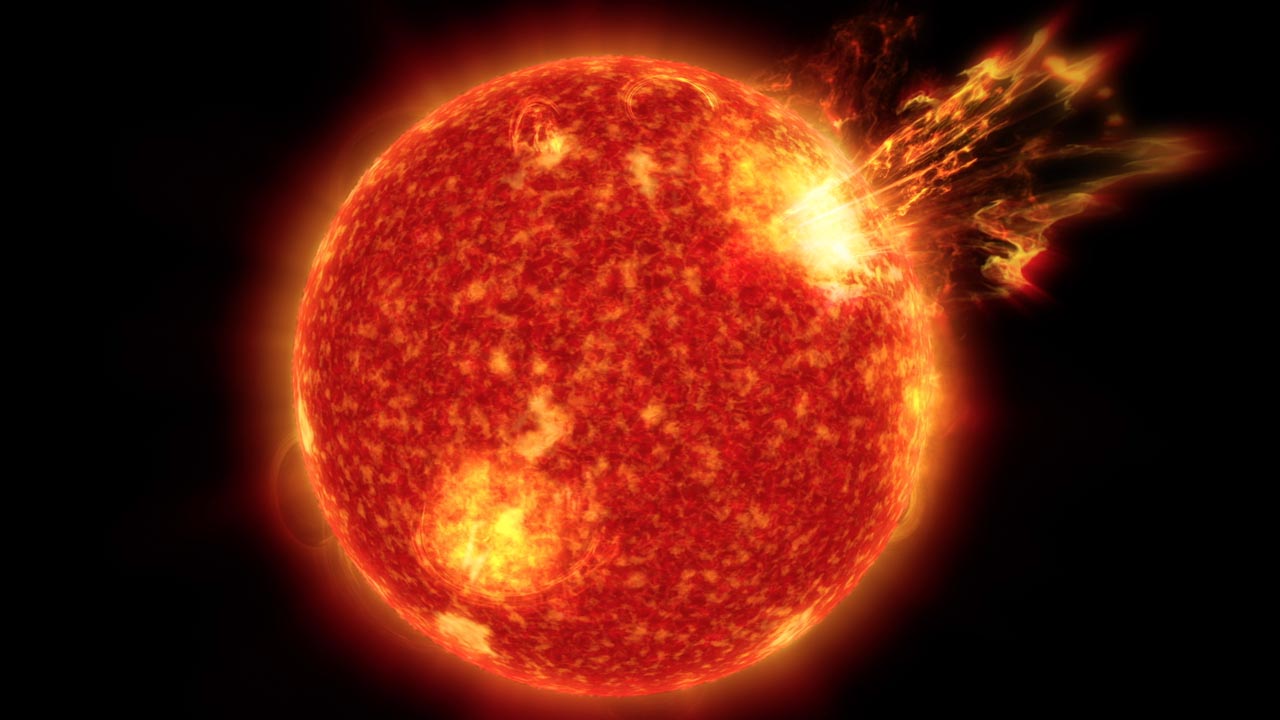

It is sunlight that causes the comet's head to shine, in much the same manner that luminous paint reacts to ultraviolet light. The comet’s tail is produced by the solar wind — a thin supersonic breeze of atomic particles blowing from the sun — and the pressure of sunlight, which pushes the gas and dust out ahead of the coma.

Old versus new

One clue about how a comet will ultimately perform is whether it’s a “new” comet, making its very first approach to the sun, or whether it’s an "old" one that has zoomed close to our star before.

New comets might be covered with a load of very light, volatile material such as frozen nitrogen, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide. Such ices can vaporize far from the sun, giving a distant comet a short-lived surge in brightness that can raise unrealistic expectations. This happened with ultimately disappointing comes such as Cunningham in 1940, Kohoutek 1973 and Austin in 1990.

But some new comets live up to the hype. In January 2007, for instance, Comet McNaught became the brightest comet in over 40 years, eventually becoming luminous enough to be visible in broad daylight.

Unpredictable!

Some small, faint comets have suddenly and unexpectedly become incredibly bright literally overnight. In October 2007, Comet Holmes brightened by a factor of 500,000 in less than two days, going from an object visible only with very large telescopes to becoming easily visible to the naked eye.

Its sudden flare may have been causedby a buildup of gas inside the comet's nucleus that eventually broke through its surface, astronomers say. Incredibly, this all took place far out in space when the comet was nearly 230 million miles (370 million km) from the sun. Who knew?

Even recent skywatching sight Comet Pan-STARRS had some surprises in store. When the comet was discovered in June 2011, forecasts indicated it might get as bright as first or even zero magnitude — in other words, as bright as the brightest stars.

Then, it was surmised that the comet was "new" and might possibly lag behind the original optimistic predictions. Until recently, that seemed to be the case; Pan-STARRS was running about one-quarter as bright. Some suggested it might not get much brighter than third magnitude, which would be less than half as bright as Polaris, the North Star.

Then without fanfare, in late February, it made a surprising comeback, reaching first magnitude as it rounded the sun on March 10.

Be careful!

While you might have gotten the idea by now that comets are notoriously bad actors and do not always follow their scripts, I should stress that many of them are well-behaved and do what is expected in a broad sense. Still, caution is advised when reading any predictions of their brightness.

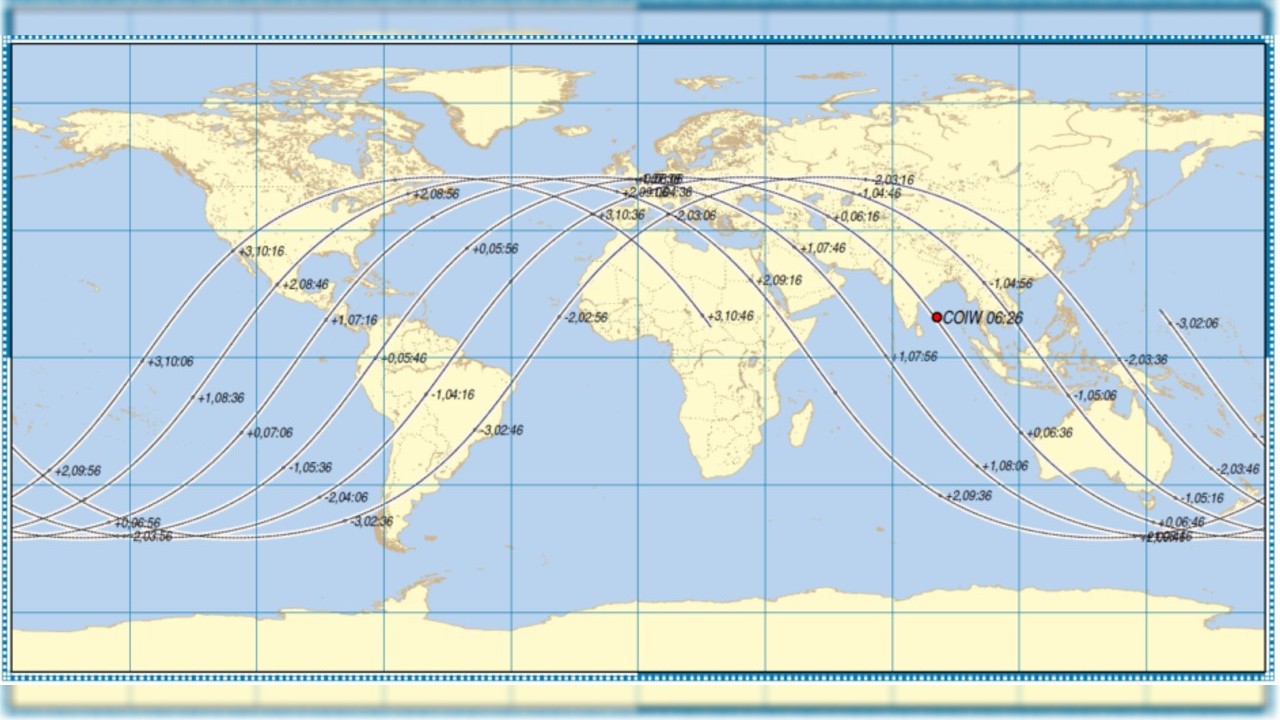

That brings us back to Comet ISON, which is expected to sweep less than three-quarters of a million miles above the sun’s surface on Thanksgiving Day (Nov. 28). Already there have been a plethora of articles promoting ISON as the “Comet of the Century.”

For an interesting analogy, baseball scouts like to catalogue the talents of players by looking at five general areas of performance in which one may define potential talent. Great ballplayers can hit for average, hit with power, field, run and throw. [Photos of Comet ISON in Night Sky]

Similarly, astronomers who catalogue potential great comets look at four general areas of performance: comets that closely approach the sun, closely approach the Earth, have a favorable projection angle for viewing the tail and high intrinsic brightness.

From these criteria, Comet ISON certainly appears to be a “can’t miss” prospect, though it is a new comet, which makes it more of a wild card.

But then again, like countless numbers of young ballplayers who had unlimited potential but failed to make the big leagues, ISON too could falter.

It could unexpectedly exhaust all of its volatile material, leaving just a small, dark solid lump to ultimately swing around the sun — meaning we may not see it all. Or perhaps upon passing through the sun’s outer atmosphere and being subjected to a temperature of around 1 million degrees Fahrenheit (555,000 degrees Celsius) or more, the comet nucleus might shatter or disintegrate.

The saga of ISON is not yet fully written, and it could still go either way. We’ll keep track of its progress in the weeks and months to come.

In the meantime, it might be worth ending with an oft-quoted axiom by the legendary comet expert Fred Whipple: “If you must bet, bet on a horse, not a comet!”

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.