Volcanic 'Devil Comet' erupts with its biggest blast yet as it races toward Earth

The icy volcanic comet 12P/Pons-Brooks, which is three times the size of Mount Everest, erupted again Nov. 14 for the fourth time since July 2023.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

An icy volcanic comet, nicknamed the "Devil Comet", erupted for the fourth time Tuesday (Nov. 14) as it races toward Earth.

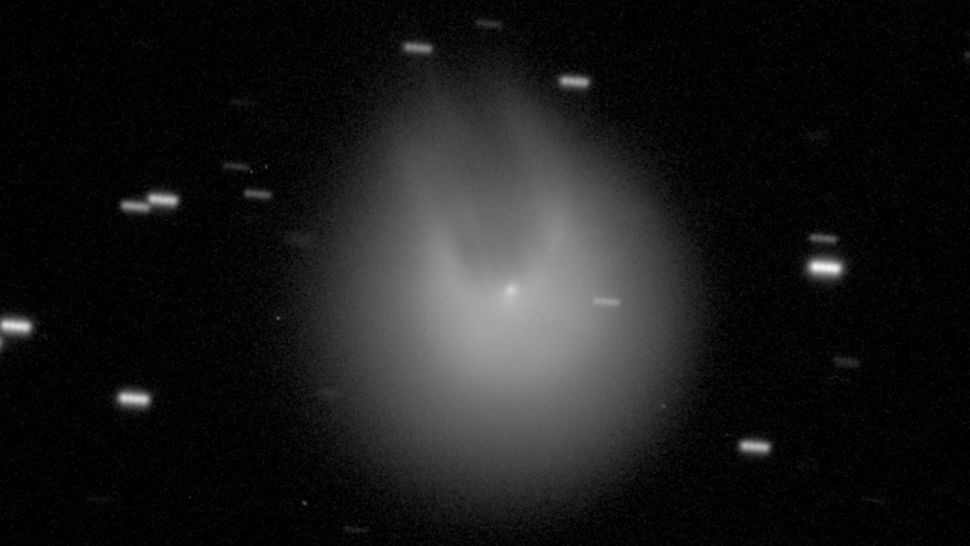

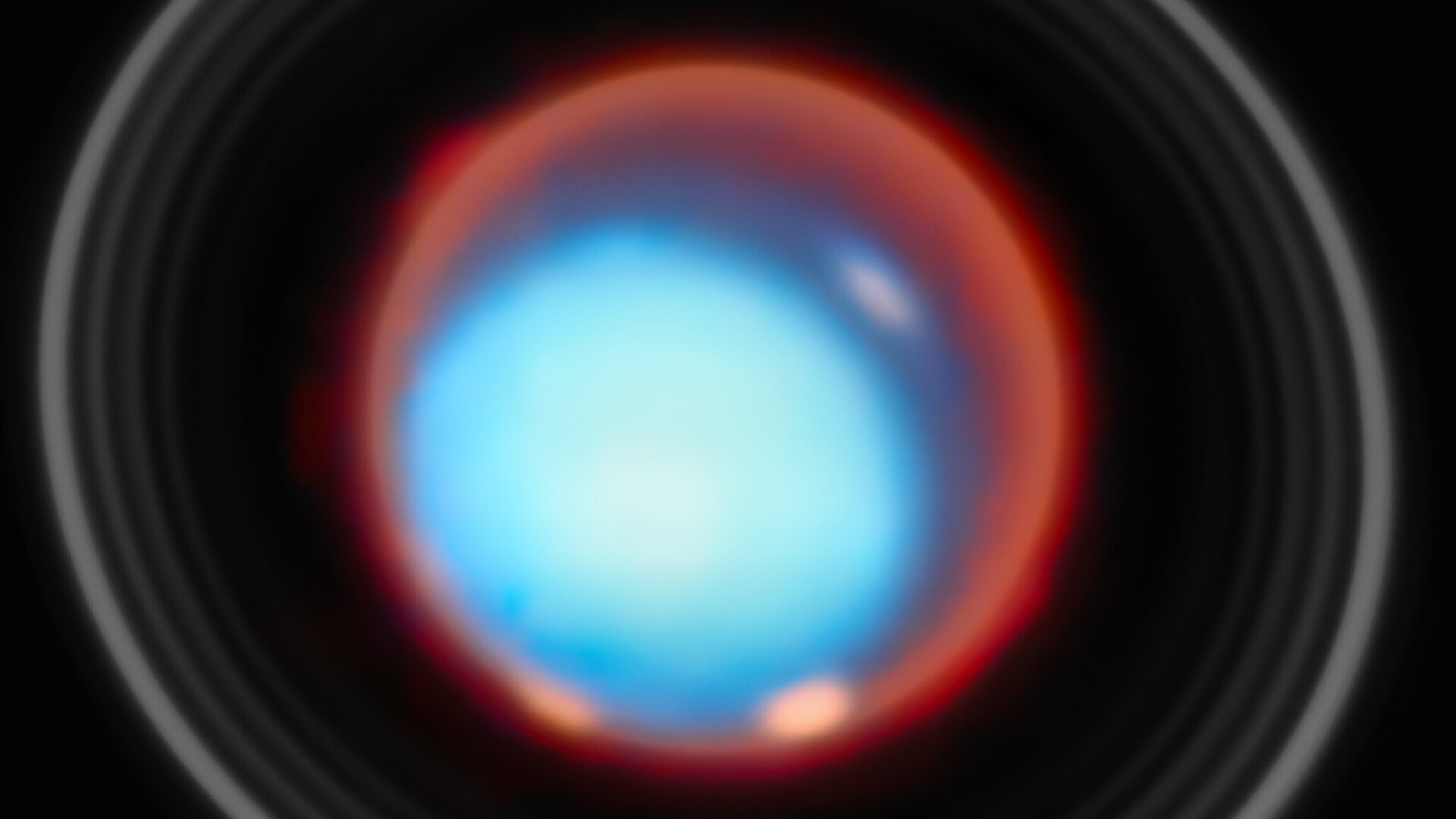

The comet, officially called 12P/Pons-Brooks, violently blasted out ice and gas and created a glowing halo that resembles devil horns. This is the largest outburst yet for the Devil Comet, which at 18 miles (29 kilometers) wide is roughly three times the size of Mount Everest.

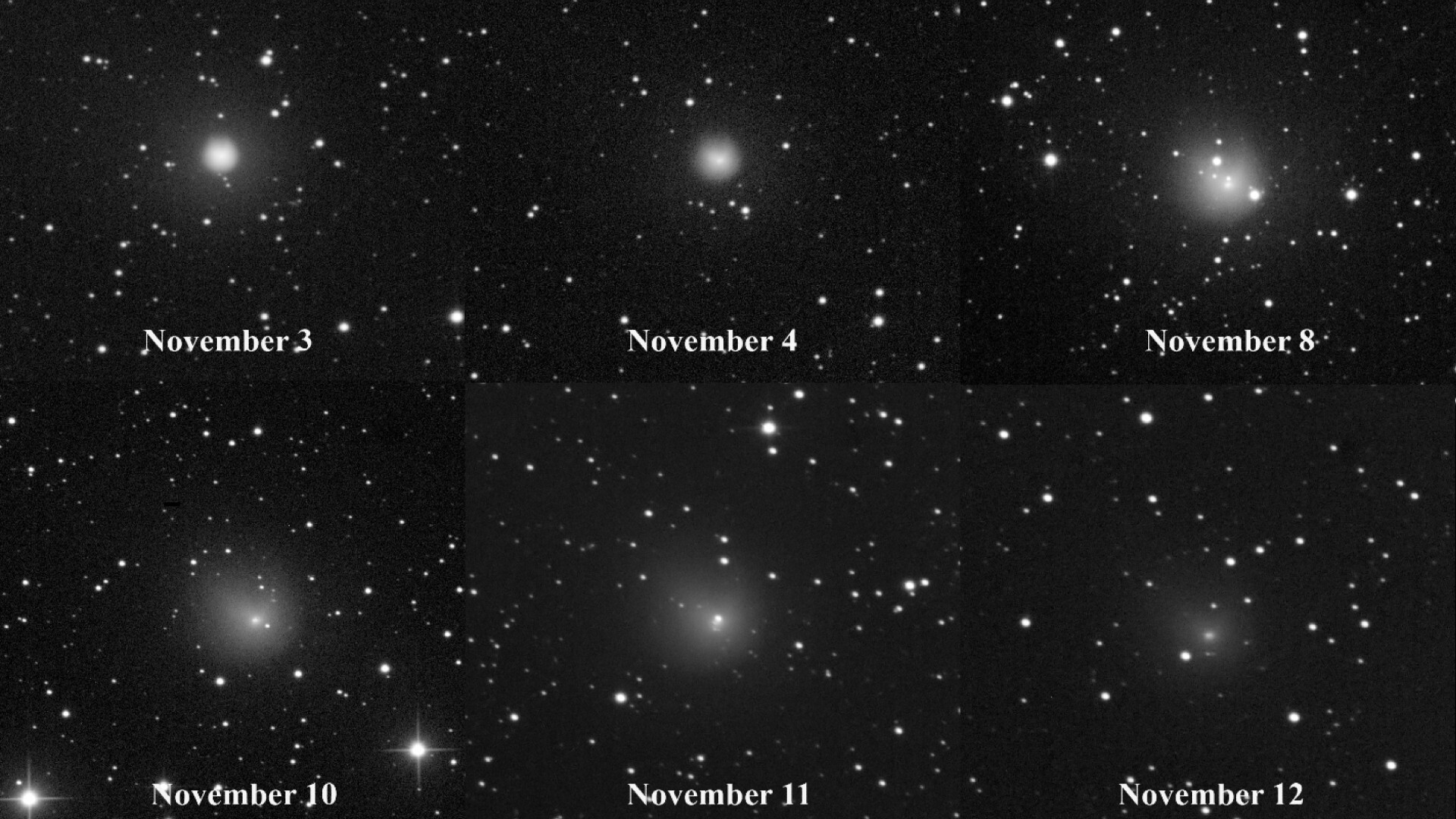

Amateur astronomer Eliot Herman spotted the major cryogenic outburst just hours after it began. The retired biology professor has been monitoring the Devil Comet — first discovered in 1812 — almost every night from his location in Arizona. Herman saw the comet undergo a 100-fold increase in brightness, according to SpaceWeather.

Related: Volcanic 'devil comet' resprouts its horns after erupting again

The cryovolcanic comet — which has a heart of ice, gas and dust within an icy outer shell — is currently racing through the inner solar system and toward the sun at a speed of 40,000 mph (64,373 km/h). That velocity is about 30 times as fast as the top speed of an F-16 fighter jet.

The view of 12P will only improve, as it approaches its closest distance to Earth on June 2, 2024. The comet will come to within 144 million miles (232 million km) of our planet — around 1.5 times the distance between Earth and the sun.

The Devil Comet will next make a close approach to the sun on April 24, 2024, when it will come closer to our star than Earth — but not as close as Venus, at 73 million miles (117 million km) away.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

As comets move toward the sun, radiation from our star hears material within them, causing solid ice to transform directly into gas . This process, called sublimation, blasts from the comet's surface and blows away solid material.

Sublimation is more explosive and dramatic for the Devil Comet than most other icy bodies. The cryovolcanic nature of 12P/Pons-Brooks allows the interior of the comet to be superheated, letting pressure build-up until it explosively cracks the comet's outer shell and sprays matter into space.

The sudden, powerful outbursts have caused a halo-like coma (tenuous atmosphere) to form around the Devil Comet, which makes it reflect more sunlight, thus meaning the coma brightens as it approaches the sun.

This ejected material also creates the coma's extraordinary horn-like appearance, which resulted in its satanic nickname. These distinctive horns result from a large and strange notch in the shell of the Devil Comet. The shell prevents cryo-material from escaping into space, thus limiting the growth of the coma in this region, while the material billows out from the comet on either side of the notch.

The Devil Comet was observed erupting for the first time in 69 years on July 20, 2023 (the anniversary of Apollo 11's historic first human moon landing in 1969, too). The comet's coma swelled out to 7,000 times the width of the comet's nucleus. The Devil Comet erupted again on Oct. 5, with a third blast happening — fittingly — on Oct. 31, Halloween.

It takes the Devil Comet 71 years to complete an egg-shaped — or elliptical — orbit of the sun. The orbit causes the comet to swing far away from the heart of our solar system, thus meaning it spends the majority of its time lurking at the outer edges of our neighborhood. Thus, each time 12P moves through the inner solar system, the comet offers astronomers a unique, practically once-in-a-lifetime chance to observe its brightening and devilish visage.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.