Signs of Mars life may be too elusive for rovers to detect

Sample return is likely our best bet to find Mars life, if it ever existed, a new study suggests.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The robots currently exploring Mars may not be capable of detecting potential traces of life on the Red Planet, a new study finds.

The twin Viking orbiters NASA sent to Mars nearly a half-century ago discovered that the Red Planet possessed liquid water on its surface early in its history, about three billion to four billion years ago. Later missions have supported these findings, suggesting that organisms might once have lived there, and might still, since life is found virtually wherever there is water on Earth.

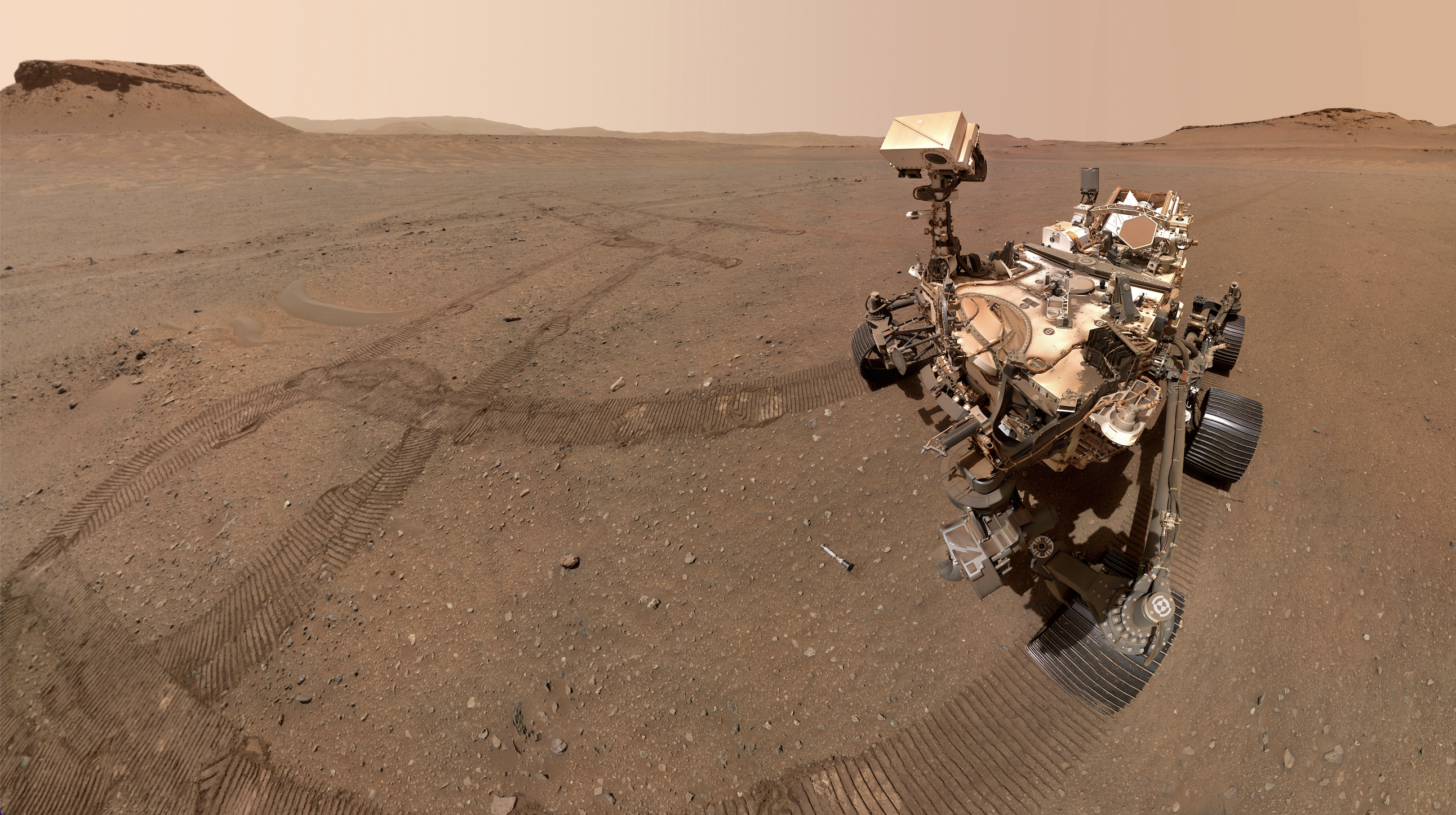

However, NASA's two Viking landers detected no unambiguous native organic chemicals within Martian soil, even at levels of parts per billion. Even the most recent, highly advanced instruments of NASA's later Curiosity and Perseverance rovers have found just traces of simple organic molecules in ancient Martian lakebeds and river deltas. And these compounds are not solid evidence of life; they could have been produced by geological processes, scientists have stressed.

Related: Life on Mars: Exploration and evidence

It remains uncertain if the hunt for past or present life on Mars has fallen short because the Red Planet has always been barren or because the probes sent there are not sensitive enough to detect any life onsite. To help solve this mystery, scientists tested instruments that are currently or may be sent to Mars alongside highly sensitive lab equipment.

The researchers analyzed samples from Red Stone, the remains of a river delta in the Atacama Desert of Chile, one of the oldest and driest deserts on Earth. These deposits, which formed under highly arid conditions about 100 million to 160 million years ago, strongly resemble Mars' Jezero Crater, which Perseverance is currently investigating.

Red Stone regularly experiences fogs that supply water for microbes that live at the site. The state-of-the-art lab techniques the scientists used found a mixture of biochemicals from both extinct and living microorganisms there. About half of the DNA sequences detected at Red Stone came from the "dark microbiome" — that is, microbes that researchers have not yet properly described.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

However, the testbed versions of instruments currently on or planned for Mars — including one 10 times more sensitive than one on Curiosity — were barely able to detect organic signs of life in Red Stone samples.

"I would have expected that the testbed instruments we tested in order to detect the evidence of life at Red Stone that we knew was there using tools you might find in any microbiology lab would fare better," study lead author Armando Azua-Bustos, of the Center of Astrobiology in Madrid, told Space.com. "And they didn't."

These findings suggest that Mars probes will find it difficult, if not impossible, to detect the kinds of low levels of organic matter expected to be on the Red Planet today if microbial life did indeed exist there billions of years ago.

"We're still learning how to detect evidence of life on Mars," Azua-Bustos said. "The current nature of the instruments sent there have their limits. But that's not because they have been badly designed. We're still on the learning curve."

The researchers suggest that future missions to Mars should aim to return samples from the Red Planet to Earth, where they can get tested by the most advanced equipment scientists have in order to help solve the puzzle of whether life ever lived on Mars. NASA and the European Space Agency aim to do just that, by the way, hauling material collected by Perseverance back to Earth as early as 2033.

Future research can analyze the dark microbiome at Red Stone. These microbes are either so different from any known microorganisms that they defy current categories, or they are remnants of the life that used to live in the area when it had water millions of years ago "that have no current relatives now that you can compare them with," Azua-Bustos said.

All in all, Azua-Bustos noted that much likely remains to be discovered at Red Stone. This new work "is like sampling one street in New York to characterize the whole of New York," he said.

The scientists detailed their findings online Tuesday (Feb. 21) in the journal Nature Communications.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us