Japan may extend Hayabusa2 asteroid mission to visit 2nd space rock

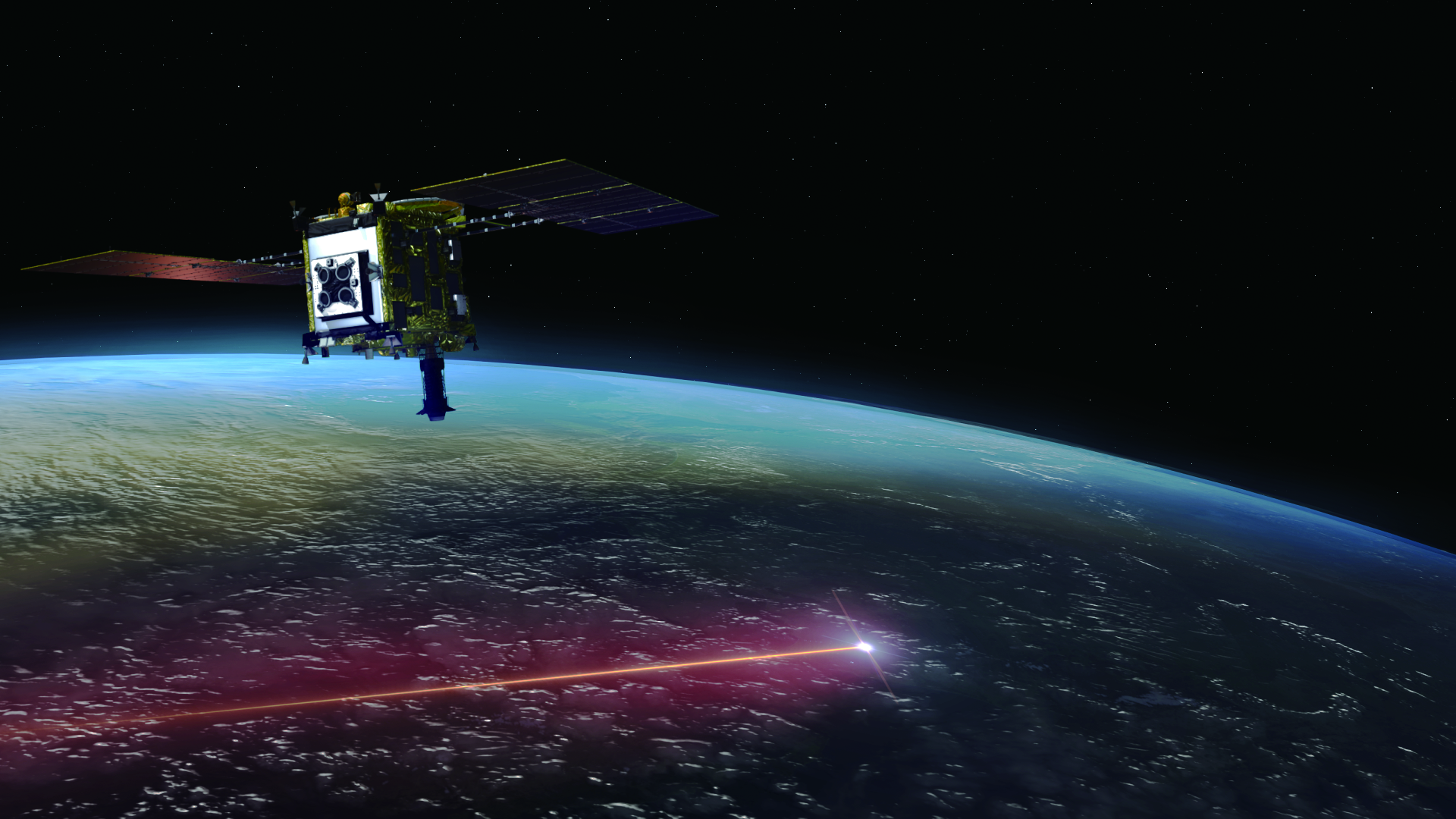

Japan's Hayabusa2 mission is headed home from an asteroid called Ryugu, carrying a very special delivery of space rock, but Earth may not be the spacecraft's final destination.

The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), which runs the mission, is evaluating a second stop for its space-rock investigation, according to recent statements. Such a mission extension, which would last more than a decade, could see Hayabusa2 orbit a second asteroid.

The opportunity for extension comes from a combination of two factors: the spacecraft's engine still holds about half its fuel and it doesn't need to land on Earth to complete the sample-return piece of its agenda. Instead, the mission's main spacecraft will deploy a small capsule packed with asteroid chunks that will tumble through Earth's atmosphere and land in the Australian Outback on Dec. 6.

Related: Japan's Hayabusa2 asteroid Ryugu sample-return mission in pictures

When JAXA engineers ran the numbers, they realized that Hayabusa2's main spacecraft could send that capsule on its way and still be poised for more adventures. The spacecraft would need to stay in the inner solar system to draw enough solar power, but the team calculated that the spacecraft will has enough fuel to visit one of 354 different destinations, according to a JAXA statement, including Venus, Mars, nearby comets and a host of asteroids.

Mission personnel have already narrowed down the spacecraft's potential second target to just two candidates, both tiny space rocks with designations rather than proper names. These objects are near-Earth asteroids, like Ryugu itself, but each is just one tenth as wide as Hayabusa2's first destination.

Despite their tiny size, both candidates are scientifically intriguing, according to JAXA, and Hayabusa2 would be able to slip into orbit around either one, rather than simply fly by, making the little asteroids even more intriguing targets.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Of course, planning orbital operations presume that the spacecraft remains in good health long enough to rendezvous with these objects, and that's a big if. Hayabusa2 was only designed to withstand its initial six-year mission, not an extra decade in the harsh environment of space. But for JAXA, there's little risk in trying beyond the cost of continuing to operate the spacecraft, that is.

In the case of either potential target, Hayabusa2 would need to make a long and winding journey, skimping on fuel and instead relying on gravitational boosts from flying by Earth, Venus or another asteroid to drive the probe to its destination, arriving only in 2029 or 2031, depending which object wins out.

While JAXA would have liked a faster arrival, there were no targets that Hayabusa2 could reach in less than five years, according to the agency.

That said, the spacecraft would be able to do science long before it reached its new target. Hayabusa2 could study the zodiacal light that reflects off interplanetary dust and look for exoplanets during quiet parts of its cruise, according to JAXA. It could study the moon during flyby maneuvers it would need to conduct around Earth to meet its target. And, depending on the final destination, the spacecraft would also need to swing past either Venus or another asteroid, offering another observation opportunity.

Then, of course, there are the asteroid destinations themselves. The two contenders are called 2001 AV43 and 1998 KY26, using the typical number-letter designations assigned to asteroids at their discovery. Both are near-Earth objects, like Ryugu and like Bennu, which NASA's sample-return mission OSIRIS-REx is currently orbiting, and each orbits the sun once every 500 or so days, according to NASA's database of such objects.

Both asteroids share several intriguing characteristics, according to JAXA's evaluation. Both are quite small, just 100 to 130 feet across (30 to 40 meters), and both spin quite rapidly, making a full rotation every 10 minutes or so. Scientists have never gotten an up-close look at such a fast-spinning small space rock, according to JAXA, which makes them particularly intriguing, since the outward force created by that spin would likely be stronger than the object's gravity.

In addition, those traits make scientists wonder whether these two space rocks are solid objects or so-called "rubble pile" asteroids like Ryugu itself, which formed when debris from a collision clumped together.

The two possible targets aren't identical, of course. 2001 AV43 appears to be a bit elongated and may be a mix of rocky materials and metal, a somewhat less common recipe for asteroids. 1998 KY26, in contrast, is rounder and is likely a more carbon-rich type of asteroid, the most common class of space rock and the same category as both Ryugu and Bennu.

Hayabusa2 could reach 2001 AV43 in November 2029, while it wouldn't be able to reach 1998 KY26 until July 2031.

As with all asteroid missions, Hayabusa2's potential second stop is balancing two different goals. There's a degree to which scientists study these space rocks just to learn about the solar system. But there's also a degree of existential angst to the work. After all, near-Earth asteroids can become a-little-too-near-Earth asteroids. While our atmosphere protects us from many of these space rocks, some make it through to cause damage at Earth's surface.

Although asteroids in the size range of these two potential targets are too small to cause the sort of cataclysmic impact that infamously wiped out large dinosaurs, these rocks can still do real damage at a local scale and are expected to hit Earth every century or handful of centuries, according to JAXA.

The most recent sizable asteroid impact, which burst into pieces over Chelyabinsk, Russia, was triggered by an asteroid likely about half the size of Hayabusa2's two potential targets, which are likely about the same size as the object that caused the Tunguska event in 1908. The more that scientists can learn about such objects in their natural environment, the better humans can prepare to defend themselves if an asteroid comes a bit too close for comfort.

JAXA will decide which target is more promising this fall, then wait for budgetary support before determining whether Hayabusa2 will make its extra stop.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.