Photons could reveal 'massive gravity,' new theory suggests

This is a radical new design compared to the world's most sensitive gravitational wave detectors.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

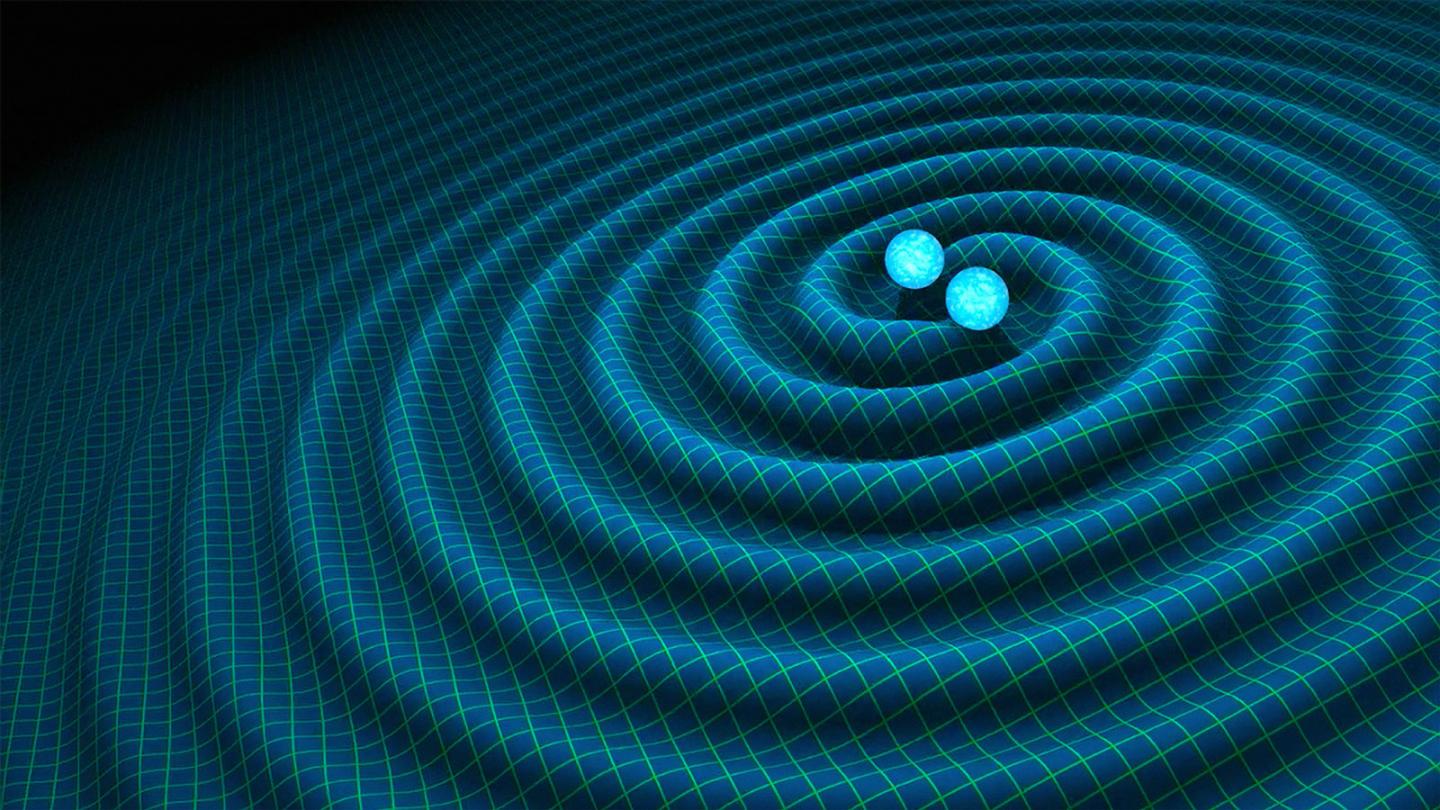

Gravitational waves, or ripples in space-time, slip through Earth all the time, carrying secrets about the universe. But until a few years ago, we couldn't detect these waves at all, and even now, we have only the most basic ability to detect the stretching and squeezing of the cosmos.

However, a proposed new gravitational wave hunter, which would measure how particles of light and gravity interact, could change that. In the process, it could answer big questions about dark energy and the universe's expansion.

The three detectors on Earth today, all together called Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) and Virgo, operate according to the same principle: As a gravitational wave moves through the Earth, it faintly stretches and squeezes space-time. By measuring how long a laser light takes to travel over long distances, the detectors notice when the size of that space-time changes. But the changes are minute, requiring extraordinarily sensitive equipment and statistical methods to detect.

Related: 8 Ways You Can See Einstein's Theory of Relativity in Real Life

In this new paper, three researchers proposed a radical new method: hunting gravitational waves by looking for effects of direct interactions between gravitons — theoretical particles that carry gravitational force — and photons, the particles that make up light. By studying those photons after they've interacted with gravitons, you should be able to reconstruct properties of a gravitational wave, according Subhashish Banerjee, a co-author of the new paper and physicist at the Indian Institute of Technology in Jodhpur, India. Such a detector would be much cheaper and easier to build than existing detectors, Banerjee said.

"Measuring photons is something which people know very well," Banerjee told Live Science. "It's extremely well-studied, and definitely it is less challenging than a LIGO kind of setup."

No one knows exactly how gravitons and photons would interact, largely because gravitons are still entirely theoretical. No one's ever isolated one. But the researchers behind this new paper made a series of theoretical predictions: When a stream of gravitons hits a stream of photons, those photons should scatter. And that scattering would produce a faint, predictable pattern — a pattern physicists could amplify and study using techniques developed by quantum physicists who study light.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Linking the physics of the tiny quantum world with the large-scale physics of gravity and relativity has been a goal of scientists since Albert Einstein's time. But even though the newly suggested approach to studying gravitational waves would use quantum methods, it wouldn't fully bridge that tiny-to-large-scale gap on its own, Banerjee said.

"It would be a step in that direction, however," he added.

Probing the direct interactions of gravitons might solve some other deep mysteries about the universe, though, he said.

In their paper, the authors showed that the way the light scatters would depend on the specific physical properties of gravitons. According to Einstein's theory of general relativity, gravitons are massless and travel at the speed of light. But according to a collection of theories, together known as "massive gravity," gravitons have mass and move slower than the speed of light. These ideas, some researchers think, could resolve problems such as dark energy and the expansion of the universe. Detecting gravitational waves using photon scattering, Banerjee said, could have the side effect of telling physicists whether massive gravity is correct.

No one knows how sensitive a photon-graviton detector of this kind would end up being, Banerjee said. That would depend a lot on the final design properties of the detector, and right now, none are under construction. However, he said, he and his two co-authors hope that experimentalists will start putting one together soon.

- 9 ideas about black holes that will blow your mind

- The 12 strangest objects in the universe

- 6 weird facts about gravity

Originally published on Live Science.

Rafi wrote for Live Science from 2017 until 2021, when he became a technical writer for IBM Quantum. He has a bachelor's degree in journalism from Northwestern University’s Medill School of journalism. You can find his past science reporting at Inverse, Business Insider and Popular Science, and his past photojournalism on the Flash90 wire service and in the pages of The Courier Post of southern New Jersey.