A first-of-its-kind asteroid thrilled astronomers. But it was just a comet fraud.

Asteroid? Trojan? Comet? It's tough out there in space.

For a week, it was a truly stunning crumb of the solar system — until scientists realized it was just a dirty hunk of ice with an identity crisis.

The twisted tale revolves around a surprising, dusty tail spotted among a clump of distant space rocks. And it begins in Hawaii, with a program called the Asteroid Terrestrial-Impact Last Alert System, or ATLAS.

ATLAS is a serious project with its sights on more existential solar system mysteries than identity fraud. Every night, its two observatories perched on Hawaiian peaks survey the sky, watching for anything that moves against the background of stars. The goal is to spot any large space rocks that may collide with Earth as soon as possible, so humans have more time to try to fend off a possible apocalypse.

Related: Photos: Spectacular comet views from Earth and space

But it turns out there are way more objects moving in the sky than there are collision-course asteroids, which means that ATLAS ends up spotting a heck of a lot of safe but intriguing things during its careful surveys — freebies for scientists.

"Even though the ATLAS system is designed to search for dangerous asteroids, ATLAS sees other rare phenomena in our solar system and beyond while scanning the sky," the project's principal investigator Larry Denneau said in a statement released by the University of Hawaii, which manages ATLAS. "It's a real bonus for ATLAS to make these kinds of discoveries."

In June 2019, ATLAS made just such a discovery, dubbed 2019 LD2. The object appeared to belong to a class of asteroids called Jupiter Trojans. Trojan asteroids get stuck in the same orbit as a planet but either running ahead of it or trailing behind it, like a posse of bodyguards. Jupiter has hundreds of thousands of space rocks in each clump, as befits the king of the solar system; 2019 LD2 is located in the vanguard cluster.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

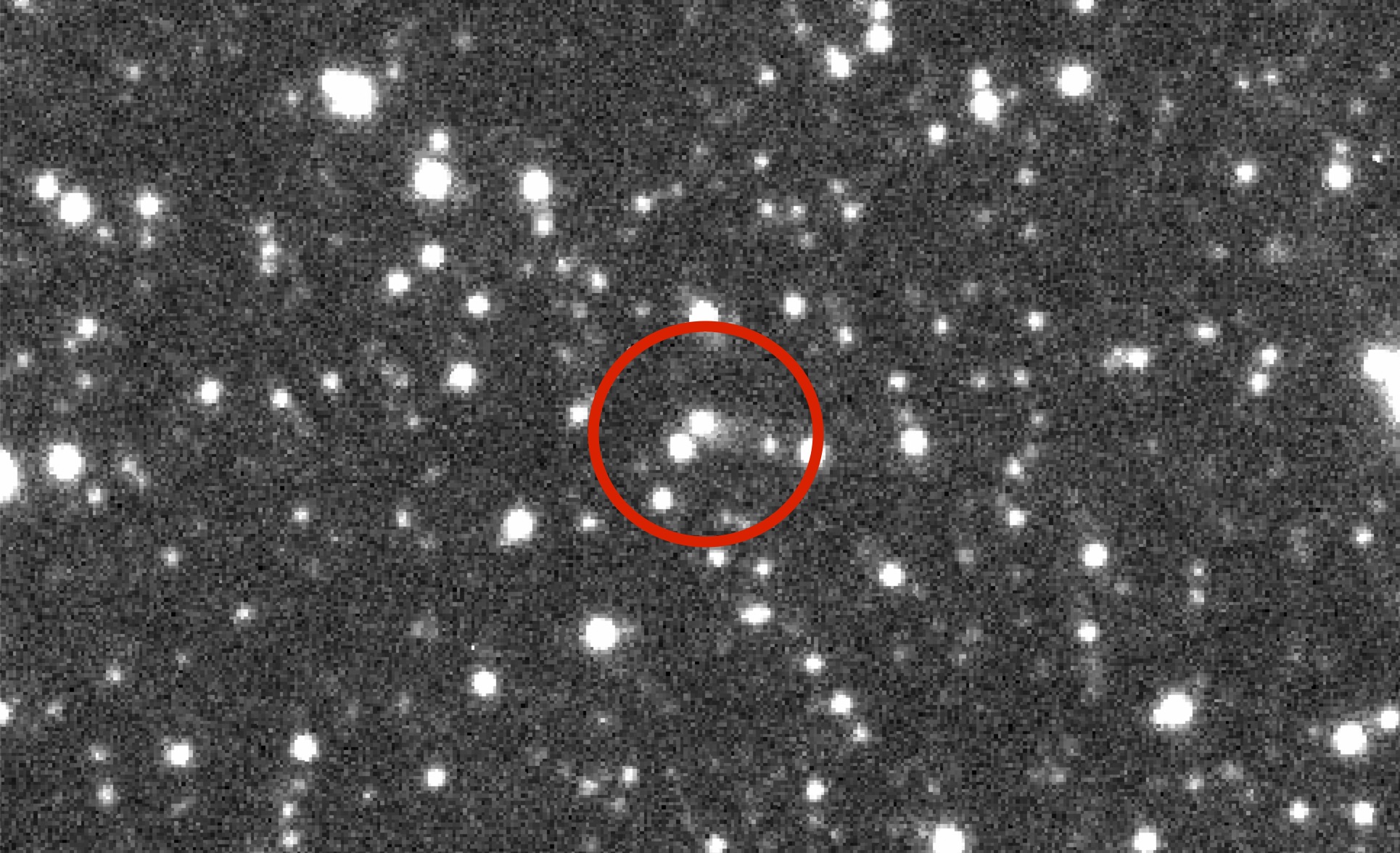

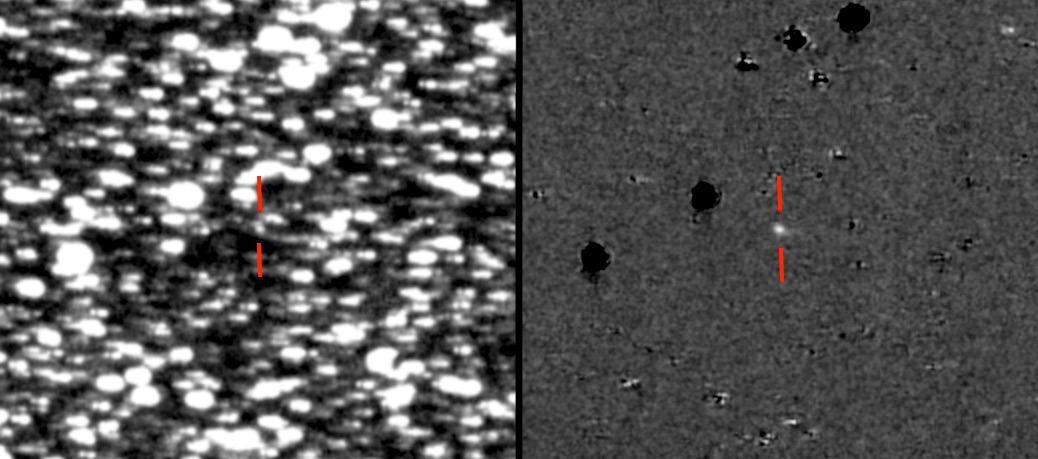

But something was strange about the new space rock, scientists found as they continued to study it in June and July of 2019: LD2 seemed to have a tail, an unusual accessory for an asteroid. Then the object passed to the far side of the sun, where astronomers could no longer study it, until the beginning of April. When the space rock did reappear, ATLAS imaged it again, and still saw a tail.

Typically, it takes a comet — a much icier piece of debris — to develop such a structure; asteroids don't usually contain enough volatile materials. Nevertheless, the observations sort of made sense, given existing hypotheses about Trojans.

Scientists have never been able to get a good look at the Jupiter Trojans, although that will change later this decade, thanks to NASA's Lucy mission. That spacecraft, scheduled to launch in October 2021, will swing through a tour of the Trojan asteroids, stopping by both leading and trailing clusters and visiting multiple rocks in each, beginning in 2027.

But that's a long time to wait, so ground-based research continues when the opportunity arises, and that's why scientists were so excited about the 2019 LD2 observations. "We have believed for decades that Trojan asteroids should have large amounts of ice beneath their surfaces, but never had any evidence until now," Alan Fitzsimmons, an astronomer at Queen's University Belfast in the U.K., said in the same statement.

It seemed like a landmark discovery, but there was just one problem: 2019 LD2, it turns out, isn't a Trojan with a tail. It's just another comet that happens to hang out with rocks, a cosmic black sheep. When the initial observing team announced their discovery, other scientists hustled to check out the strange object.

And they realized that the mystery rock isn't a tailed asteroid at all — it's a comet, plain and simple, according to a new statement from the University of Hawaii. A closer look at the path the object — now dubbed Comet P/2019 LD2 to reflect its true identity — suggested its presence in the swarm of asteroids was always a coincidence and that it won't be masquerading with the Trojans for long.

Instead, LD2 seems to belong to a class called the Jupiter-family comets, of which scientists have identified about 400 so far. These objects orbit the sun more closely than other comets do, making a complete lap in 20 years or less. But they also orbit close enough to Jupiter that the massive planet can rattle them around.

For LD2, Jupiter seems to knock its orbit around every few decades. The most recent such interaction ricocheted it into the Trojan cluster and laid the groundwork for a scientific puzzle.

The next will send it on a new adventure. Maybe scientists will get to tag along this time.

- That's the way the comet crumbles: Hubble image shows remains of Comet ATLAS

- Interstellar Comet Borisov shines in incredible new Hubble photos

- Now you can see every comet photo (& more) from Europe's Rosetta probe. Enjoy!

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.