A billion years from now, a lack of oxygen will wipe out life on Earth

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Matthew Warke, Research Fellow, School of Earth & Environmental Sciences, University of St Andrews

Earth will not be able to support and sustain life forever. Our oxygen-rich atmosphere may only last another billion years, according to a new study in Nature Geoscience.

As our Sun ages, it is becoming more luminous, meaning that in the future Earth will receive more solar energy. This increased energy will affect the surface of the planet, speeding up the weathering of silicate rocks such as basalt and granite. When these rocks weather the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide is pulled out of the atmosphere and through chemical reactions locked in carbonate minerals. In theory, the Earth should start to cool down as carbon dioxide levels fall, but in around 2 billion years this effect will be negated by the ever-harshening glare of the Sun.

Carbon dioxide, along with water, is one of the key ingredients that plants need to perform photosynthesis. With falling carbon dioxide levels, less photosynthesis will occur and some types of plant may die out altogether. Less photosynthesis means less oxygen production, and gradually oxygen concentrations in Earth’s atmosphere will drop, creating a crisis for other forms of future life.

So, when will this happen? To find this out researchers from Japan and the US used computer simulations to model the future evolution of the carbon, oxygen, phosphorous and sulphur cycles on the surface of the Earth. They also considered climate evolution and how the surface of the Earth (the crust, oceans and atmosphere) interacts with the planet’s interior (the mantle).

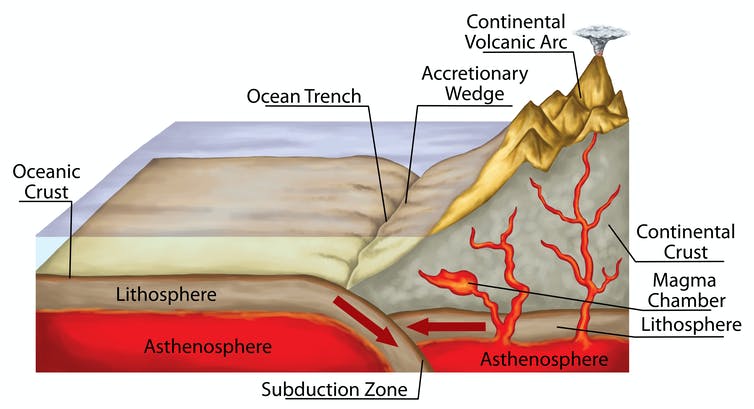

They modelled two theoretical scenarios: an Earth-like planet with an active biosphere, and a planet without an active biosphere. Interestingly, both scenarios produced broadly similar results: oxygen levels started to fall drastically at around 1 billion years in the future. This finding suggests that while falling levels of carbon dioxide and plant photosynthesis do affect oxygen levels, the effect of this process is secondary to long-term interactions between the mantle and surface environments. In short, it is the balance between the geochemistry of which rocks enter the mantle during subduction (see diagram below), and which gases are emitted from the mantle via volcanoes, that seems to mostly affect how long Earth’s atmosphere will remain oxygen-rich.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The authors of the study conclude that our oxygen-rich atmosphere may only last around 1.08 billion more years. To put that in context, oxygen only started to accumulate in Earth’s atmosphere 2.5 billion years ago – during the Great Oxidation Event – and it is likely that oxygen levels stayed fairly low for most of the planet’s history, only rising to near modern levels following the evolution of land plants around 400 million years ago.

Read more: Billions of years ago, the rise of oxygen in Earth’s atmosphere caused a worldwide deep freeze

The end of oxygen would almost certainly mark the end of Earth being able to support complex, aerobically respiring, forms of life. Though the details are debated, and other environmental factors are at play, scientists have long noted that the evolution and radiation of complex life on Earth seem tied to periods of relative oxygen abundance.

The authors of this study estimate that the total habitable lifetime of Earth – before it loses its surface water – is around 7.2 billion years, but they also calculate that an oxygen-rich atmosphere may only be present for around 20%–30% of that time.

Why does this matter? Imagine we were aliens on another world scanning the heavens for signs of life by looking for oxygen and ozone in the atmospheres of exoplanets. If our instruments passed over Earth 2 billion years from now, or 2 billion years ago, we might interpret a false negative – that such planets lacked a reliable “biosignature” – and move on with our search.

The same problem faces astronomers and planetary scientists today: what kind of exoplanets should we target, and what is a reliable biosignature of alien life? Habitability is not just a place around a star but a time in a planet’s evolution, and we must remain aware that we are limited to what we can see right now.

The future of our atmosphere bears a strong resemblance to its distant past: low in oxygen, rich in methane (if not carbon dioxide) with the possibility of organic hazes. As the authors of the new study suggest, using Earth as an analogue we might need to think more broadly about which gases to look for in exoplanet atmospheres and that we may need to rethink our interpretations of what those gases may indicate.

We need to better understand the history of our own atmosphere’s evolution over time and how the surface and interior of our planet evolved together. Only then will we be better placed to determine whether there is life living in the glare of other suns.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook and Twitter. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

I am a geologist and geochemist specialising in the evolution of Earth's atmosphere over geological time.

My current research revolves around trying to understand how atmospheric redox proxies are preserved in the rock record. Specifically, I use multiple oxygen and sulfur isotopes to track fluctuations in atmospheric oxygen concentration across Earth history.