Star Caught in Act of Birth

This story was updated June 22 at 12:40 p.m. EDT.

The youngest unborn star currently known ? an object soearly in its formation that it isn't fully developed into a true star ? hasbeen caught on camera in a new study.

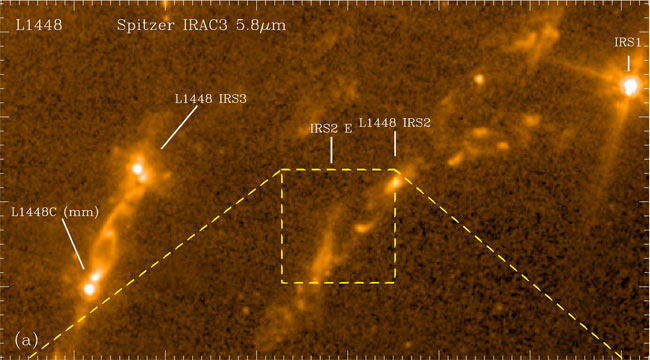

Astronomers glimpsed the future star using the SubmillimeterArray in Hawaii and the infrared Spitzer Space Telescope. The object, which isestimated to be only a few thousand years old, has just begun pulling matter infrom a surrounding envelope of gas and dust.

"It's very difficult to detect objects in this phase ofstar formation, because they are very short-lived and they emit very littlelight," said lead author Xuepeng Chen, a postdoctoral associate at YaleUniversity, in a statement. [Photos:The infrared universe.]

The team of astronomers was able to detect the faint lightemitted by the dust surrounding the object. In the images, however, the objectis difficult to see because that light is not emitted in infrared wavelengths,a press representative from Yale University told SPACE.com.

The object, known as L1448-IRS2E, is located in the Perseus star-formingregion, which is approximately 800 light-years away, within our own Milky Waygalaxy. Early calculations estimate that the object is approximately a fewthousand years old, the Yale spokesperson said.

The study's authors include astronomers from Yale, theHarvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, and the Max Planck Institute forAstronomy in Germany. The study was published in the June 1 issue of the AstrophysicalJournal.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Stars form from large, dense regions of gas and dust calledmolecular clouds, which exist throughoutthe galaxy.

The researchers suspect that L1448-IRS2E is in between thepre-stellar phase - when a particularly dense region of a molecular cloud firstbegins to clump together - and the protostar phase, when gravity has pulledenough material together to form a dense, hot core out of the surroundingenvelope.

Typically, most protostars are between one to 10 times asluminous as our sun, and their large, dust envelopes glow at infraredwavelengths. But, since L1448-IRS2E is less than one-tenth as luminous as thesun, the astronomers believe that the object is simply too dim to be considereda true protostar.

They have, however, discovered that the object is ejectingstreams of high-velocity gas from its center, which confirms that some sort ofpreliminary mass has already formed, and the object has developed beyond thepre-stellar phase.

This ejection of material is seen in protostars as a resultof the magnetic field surrounding the newly-forming star. But, this outflow hasnot been observed at such an early stage until now.

The researchers are hoping to use the new Herschel spacetelescope, which launched in May 2009, to look for more of these objects thatare caught between the earliest stages of star formation. This will allowastronomers to better understand howstars grow and evolve

"Stars are defined by their mass, but we still don'tknow at what stage of the formation process a star acquires most of itsmass," said Hector Arce, one of the authors of the study and an assistantprofessor of astronomy at Yale University. "This is one of the bigquestions driving our work."

- Top 10 Star Mysteries

- Spectacular Nebulas in Deep Space

- Gallery - Stars, Nebulas and More

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.