3D Modeling Shakes Up Planet-Formation Theory

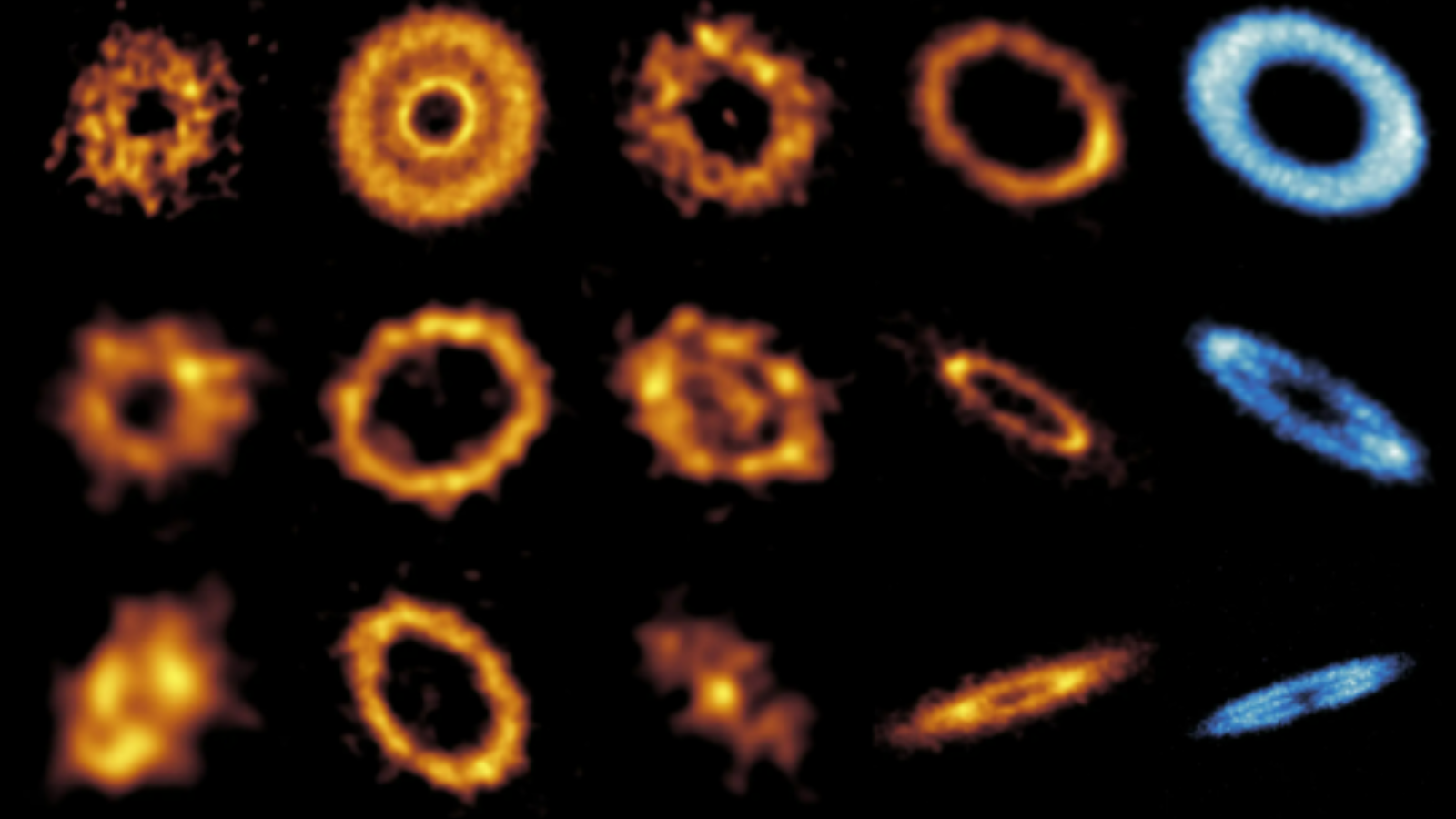

Gas-rich planets such as Jupiter and Saturn grew from a disk of dust and gas which eventually crumpled like a piece of paper under its own gravitational instability -- or so one theory goes.

Now a computer simulation suggests that this idea falls apart under the turbulent forces within early protoplanetary systems.

The old, favored theory relies on the protoplanetary dust disk becoming denser and thinner until it reaches a tipping point, where it becomes gravitationally unstable and collapses into kilometer-sized building blocks that form the basis for gas giants. But 3D modeling has shown for the first time that turbulence prevents the dust from settling into the dense disk necessary for gravitational instability to work

"It has been known since the '80s that there have been problems with that theory, but no one had gotten around to doing 3D simulations," said Joseph Barranco, an astrophysicist at San Francisco State University in Calif.

Ripples on a pond

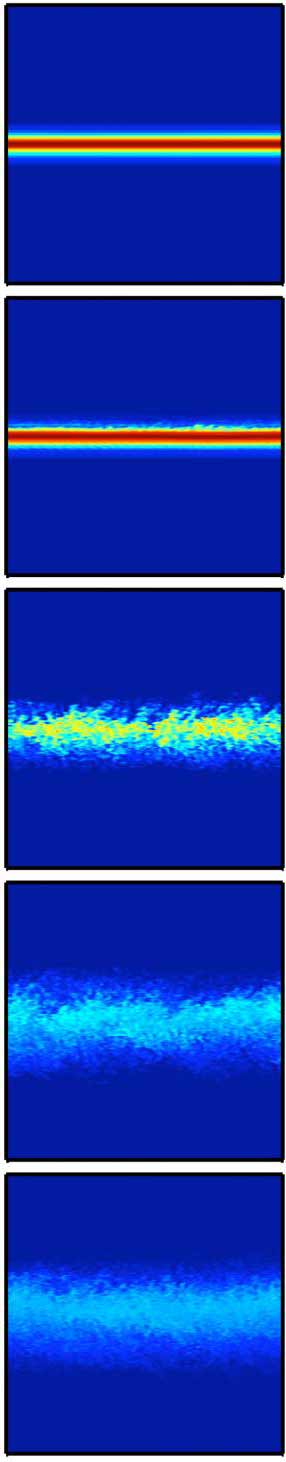

Scientists have long held that dust in a protoplanetary disk ends up sandwiched between an upper and lower layer of gas. But Barranco modeled how the gas layers flow at different speeds over and beneath the dust layer, which creates turbulence.

"What we found is that, like wind blowing over water on a pond, you get ripples," Barranco told SPACE.com. His research showed that the ripples prevent the dust from ever settling into the thin, dense middle layer.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The idea bears strong resemblance to the phenomenon of vertical shear, where wind speeds change drastically at different altitudes. This can cause dangerous turbulence for jetliners flying through Earth's atmosphere.

Another factor which seems to keep the dust layer stirred up is the Coriolis Effect. This occurs on Earth when a jetliner tries to fly in a straight line, but ends up in a curved path because the planet rotates beneath it. Winds may also fall prey to this rotation effect, which feeds into the formation of hurricanes.

Previously, some researchers had hoped that radial shearing -- which occurs when the inner ring of a dust disk rotates at faster speeds than the outer rings -- would help counteract the other turbulent forces. However, Barranco's simulation showed that the Coriolis Effect and vertical shearing usually proved stronger.

Computing planetary evolution

Planet formation theory has itself undergone periods of turbulent change in recent years. Early interest during the 1970s and 1980s eventually died down, only to pick up again in the 1990s when astronomers began finding planets orbiting other stars.

"Planet formation theory was formerly quiet, because we only had our own solar system," Barranco noted. Now scientists scramble to figure out a theory of planet formation that can account for the gas giants orbiting the many different systems observed so far.

Simulations of turbulent forces only arose in 3D during recent years with the advent of supercomputing. Barranco used hundreds of individual computer processors working together in parallel to each tackle a small piece of the puzzle. His study marks the first 3D modeling of such planetary formation, and appears in the latest issue of The Astrophysical Journal

As for explaining planet formation, the astrophysicist wants to reexamine his 2005 research that raised the idea of hurricane-like storms in protoplanetary disks. The quiet eye or center of such storms could theoretically have provided a haven for dust to clump up and provide the seeds for planets, even with chaos swirling all around.

"It's an incredibly challenging field," Barranco said. "We can't observe planetary formation, but we know that planets form because we're standing on one."

Jeremy Hsu is science writer based in New York City whose work has appeared in Scientific American, Discovery Magazine, Backchannel, Wired.com and IEEE Spectrum, among others. He joined the Space.com and Live Science teams in 2010 as a Senior Writer and is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Indicate Media. Jeremy studied history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania, and earned a master's degree in journalism from the NYU Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. You can find Jeremy's latest project on Twitter.