Laser Could Aid Search for Life on Mars

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The searchfor past life on Mars just got a new tool in its tool belt with an instrumentthat zaps bits of minerals off rocks and analyzes those pieces for the remainsof living cells.

NASAorbiters and rovers have found abundant evidence that liquid wateronce flowed on the surface of Mars, and that evidence of water raises thepossibility that the red planet once harbored life, even if onlytiny microbes.

Othermissions have looked at the question of life on Mars more directly. The U.S. Vikingmissions of the 1970s and ?80s tested Martian dirt for life directly, butdidn?t find it. NASA's PhoenixMars Lander is approaching the end of its mission to analyze the ice-richdirt of Mars' arctic region for signs of organics.

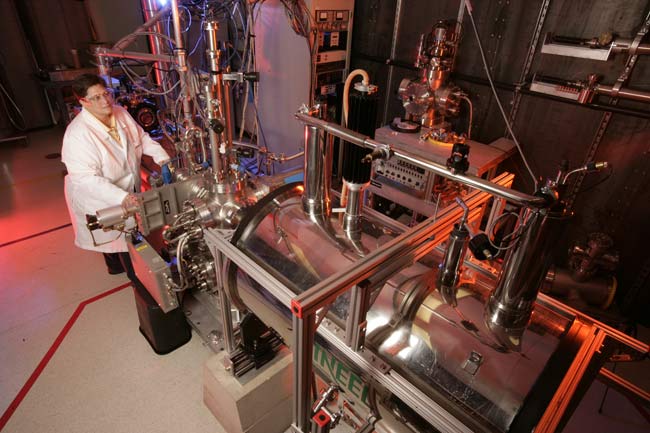

But whatscientists would really love is to get their hands on a sample of Mars andbring it back to Earth. That's where this instrument, which is being developedby researchers at the Idaho National Laboratory (INL), would come in.

How itworks

Theinstrument uses a "point-and-shoot" laser technique called laserdesorption mass spectroscopy to analyze mineral samples. The researchers focusa laser beam on a spot less than one-hundredth the width of a pencil point andthe laser knocks off microscopic fragments of the mineral.

If thereare any organics in the sample, the mineral fragments react with them to formions (atoms or molecules that have lost or gained an electron). Theinstrument's mass spectrometer can detect the ions and the team can study thepattern they create to see if it shows any signatures that could belong tospecific biomolecules.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Withfunding from NASA's Astrobiology program, INL's Jill Scott and her team havebeen running tests with the instrument and what she calls "Earth analogsof Martian rocks" to see which minerals are the best bets for finding astrong signal in a Martian sample. It will also give futuremissions to Mars a guideline for what minerals to pick up and bring home;Scott's team will be able to tell NASA, "Here's your most promisingchoices. Go after these."

"Someminerals just don't work well," Scott said. Iron oxidesparticularly don't work, which Scott said is "too bad" because Marsis what she calls "the rust planet."

So far,halite (or rock salt) and jarosite give distinct patterns when zapped if theyhave organic molecules in them. The team has also tested thenardite samplestake from the evaporated Searles Lake bed in California. Thenardite is thoughtto be a component of the Martian surface and because it is left behind whenlakes dry up, its presence could in a sample could mean that water ? and hencelife ? was once present in the area.

Scott andher team also created artificial thenardite samples containing traces ofstearic acid, which is left behind by dead cells, and glycine, the simplestamino acid used by life on Earth. (Amino acids are the building blocks ofproteins.)

All of theexperiments showed a distinct ion pattern that didn't appear when thenarditewas tested alone, suggesting that the pattern was showing a signature of theadded biomolecules.

Thebiomolecules could be detected at concentrations as low as 3 parts per trillion,the researchers recently reported in the Geomicrobiology Journal. Suchhigh sensitivity is crucial to the search for signs of life on Mars becausethose signs could be very small.

"They'reprobably going to be few and far-between," Scott said.

NASA isplanning on flying a different laser to zap rocks on the upcoming MarsScience Laboratory mission. The laser will also give of dust that can beanalyzed by mass spectrometers to learn their composition.

Why it'sbetter

There areother techniques that can detect organics in rocks, but they require extractingthe organic material from samples, which can be "very sample-consuming andtime consuming," Scott said.

You canonly bring so many samples back from Mars, and you don't want to waste what youhave, Scott said.

These othermethods would also be impractical to do on Mars itself because of all thesample preparation involved.

"Ifyou're going to be doing this on Mars, you're not going to want to do samplepreparation, Scott said.

Scott andher team would like to work on making the instrument smaller so that it couldbe sent to Mars, opening up the sampling possibilities, but for now they lackthe funding.

They arealso working to improve the laser on the instrument, which is now only ionizingabout 10 percent of all the biomolecules in a sample. This step would improvethe instrument's detection capabilities.

"There'sstill a lot to be done," Scott said.

- Video - Life on Mars: The Search Continues

- Video - Looking for Life in All the Right Places

- Mars Madness: A Multimedia Adventure!

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.