Space Shuttle Mission Loaded with 'Hope'

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

There's a lot of hope packed aboard the shuttle Discovery,bound for the space station.

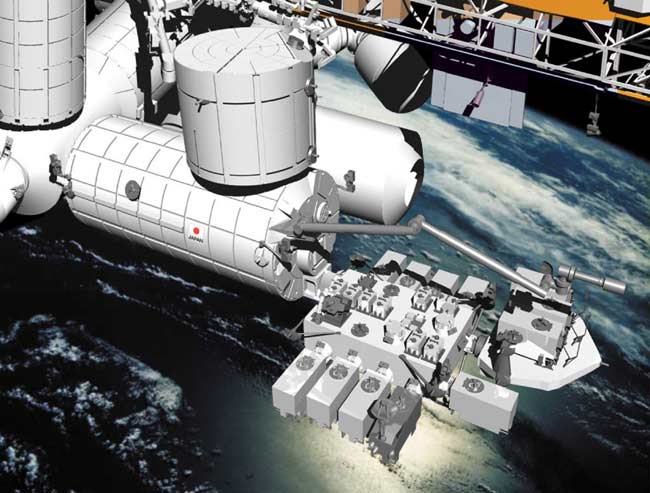

Kibo ("Hope" in Japanese) is set to be the newest,largest laboratory on the International Space Station (ISS). The tour bus-sizedroom built by Japan is scheduled to launch aboard Discovery's STS-124 mission Saturdayafternoon from NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Fla.

"This is a big milestone for the Japanesecommunity," said Japanese astronaut Akihiko Hoshide, whowill ride aboard Discovery as a mission specialist to help install hiscountry's new lab. "A lot of people worked on this for 20-plusyears, so this is really a mission to make a dream come true. It's the same forme."

The massive cylindrical room is 36.7 feet (11.2 meters) longand 14.4 feet (4.4 meters) wide. When fully-assembled, it will weigh 15.9 tons(31,800 pounds) ? about the heft of four adult elephants. It will fit up to 23racks, which can each be loaded with equipment to conduct scientific research.So far, experiments are planned in fields such as life science, materialsscience and fluid mechanics.

One of the first experiments planned for Kibo is a study ofhow heat and atoms move within materials without gravity to pin them down.

"You're looking at surface convection and flow, andstudying it in a way you couldn't possibly do on the ground," said Gregory Chamitoff, a mission specialist who will flyaboard Discovery and stay at the orbital lab for a six-month mission."It has really amazing applications ? it's really fundamental."

The $1 billion Japanese laboratory's immense size and itswide array of tools and equipment make it ideal for scientific investigations.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"I think it's the Lexus of space station modules,"STS-124 commander Mark Kelly said in a pre-flight interview.

One of Kibo's special features will be a porch-like outdoorfacility that can house experiments in the vacuum of space. These will be ableto test the effects of the space environment, including radiation, null gravityand a lack of pressure, on different materials.

"The Kibo module will have a uniqueness once we get theexposed platform installed," Hoshide said. "Then we'll have a lot ofexternal payloads, including astronomy, aerospace measurements, measuringradiation. So that portion is one of the unique characteristics of themodule."

The upcoming space shuttle mission is the second of threetrips to the space station to install various elements of Kibo. The laboratoryis so large it would be too heavy to take up in one trip fully-assembled. Nextweek's journey is slated to bring up its largest main component, the JapanesePressurized Module, as well as the lab's robotic arm, which will be used toperform science experiments on Kibo's outdoor section.

The lab wasn't originally intended to dwarf all other spacestation components, but when most agencies decided to scale down theircontributions during the station's numerous redesigns, Japan stuck with itsoriginal plan for the Kibo module.

"I think what happened is after the redesign of thespace station, everyone decided to reduce the size [of their components],"Hoshide said. "For Japan, we thought that the redesign process itselfwould be more costly, so we decided not to change the design so much, andthat's why we ended up being the biggest module. It's usually the other wayaround: Japanese products should be smaller."

- NEW VIDEO: Space Shuttle Bloopers

- VIDEO: Danger on the Pad

- Image Gallery: Shuttle Mission Diary: NASA's STS-123

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.