Technical Glitch Delays Launch of NASA's ICON Satellite on Pegasus Rocket

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

A NASA mission to loft a satellite from an airplane to probe Earth's atmosphere at the edge of space has been delayed at least one more day due to a glitch with its rocket that was detected just before launch early Wednesday (Nov. 7).

The Stargazer L-1011 carrier plane carrying NASA's Ionospheric Connection Explorer satellite, or ICON, had already taken off from its staging ground at Florida's Cape Canaveral Air Force Station when an issue was detected on the Northrop Grumman Pegasus XL rocket that was to have launched the satellite from the air at 3:05 a.m. EST (0705 GMT). The next launch opportunity for ICON is on Thursday (Nov. 8), NASA officials said.

"NASA and Northrop Grumman scrubbed today's launch of #PegasusXL due to off-nominal data received during the captive carry flight," representatives with Northrop Grumman, which built the rocket, said in a Twitter update after the launch scrub. The L-1011 Stargazer carrier aircraft has returned to Cape Canaveral Air Force Station and an investigation into the anomaly will begin soon, they added.

Article continues belowThe launch scrub is the latest in a string of delays for the ICON mission over the last year. The satellite was originally scheduled for a launch on Dec. 8, 2017, before rocket issues forced NASA to postpone it deep into 2018. The initial launch plan for ICON called for its Stargazer L-1011 to take off from a U.S. Army base on the Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands of the Pacific Ocean. After the initial delays last year, NASA moved the staging ground for the launch to Florida's Cape Canaveral Air Force Station.

NASA's ICON satellite is in good health as engineers assess the issue with its Pegasus XL booster, Northrop Grumman representatives said.

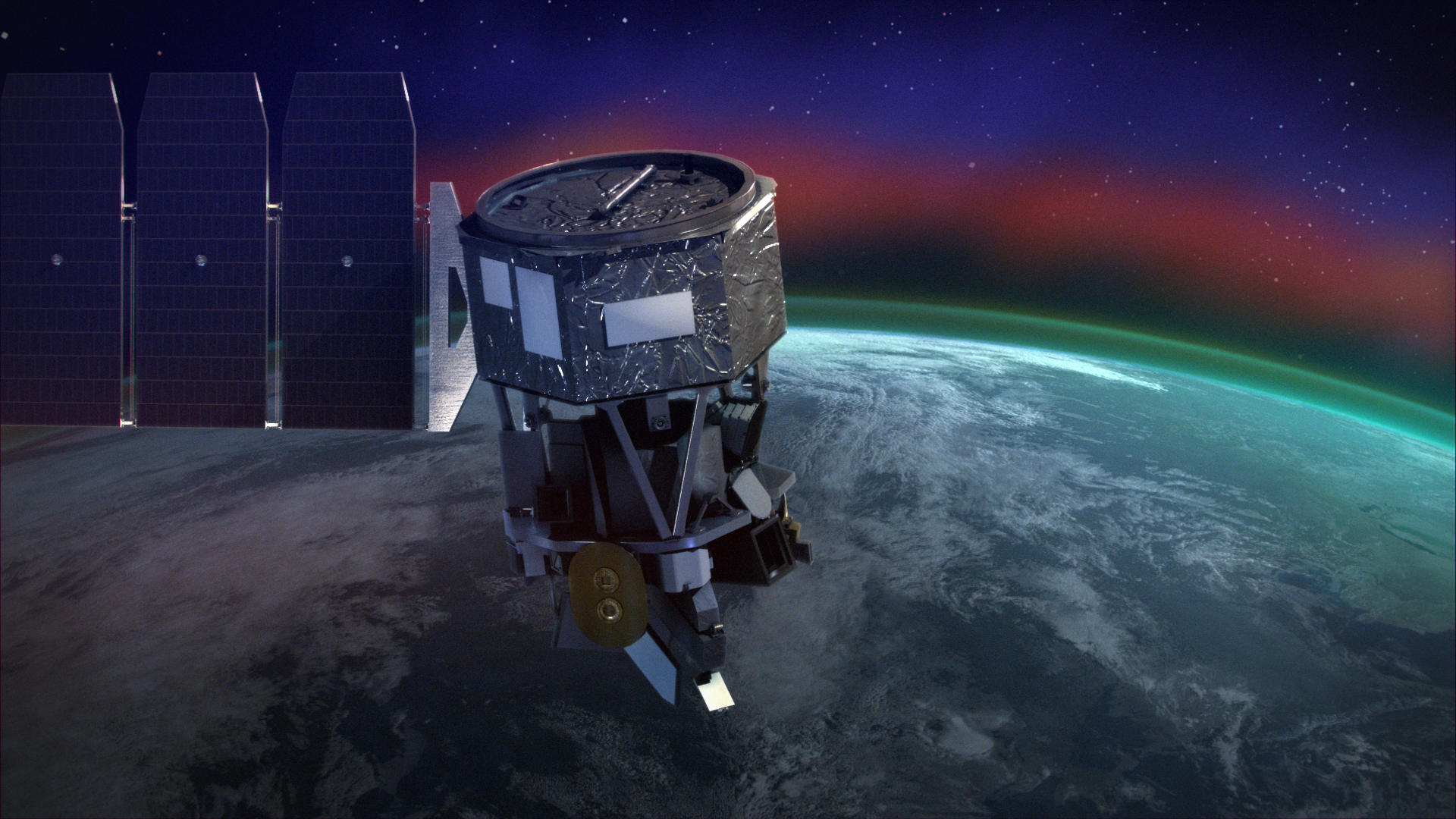

ICON is a $252 million mission to study Earth's ionosphere, a level of Earth's uppermost atmosphere ionized by the sun's radiation, like never before. The satellite will orbit about 360 miles (575 km) above Earth and use four different instruments to track how terrestrial winds and the sun's own solar wind shape the ionosphere, which covers a region roughly 50 to 400 miles (80 to 645 km) above the planet. Scientists hope the spacecraft will help understand how those winds impact the communications and GPS signals we send through the ionosphere, as well as the satellites and spacecraft in low-Earth orbit (like the International Space Station) that fly through parts of the atmospheric layer, NASA officials said.

Email Tariq Malik at tmalik@space.com or follow him @tariqjmalik. Follow us @Spacedotcom and Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Tariq is the award-winning Editor-in-Chief of Space.com and joined the team in 2001. He covers human spaceflight, as well as skywatching and entertainment. He became Space.com's Editor-in-Chief in 2019. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. He's a recipient of the 2022 Harry Kolcum Award for excellence in space reporting and the 2025 Space Pioneer Award from the National Space Society. He is an Eagle Scout and Space Camp alum with journalism degrees from the USC and NYU. You can find Tariq at Space.com and as the co-host to the This Week In Space podcast on the TWiT network. To see his latest project, you can follow Tariq on Twitter @tariqjmalik.