1st Known Interstellar Visitor Gets Weirder: 'Oumuamua Likely Had 2 Stars

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

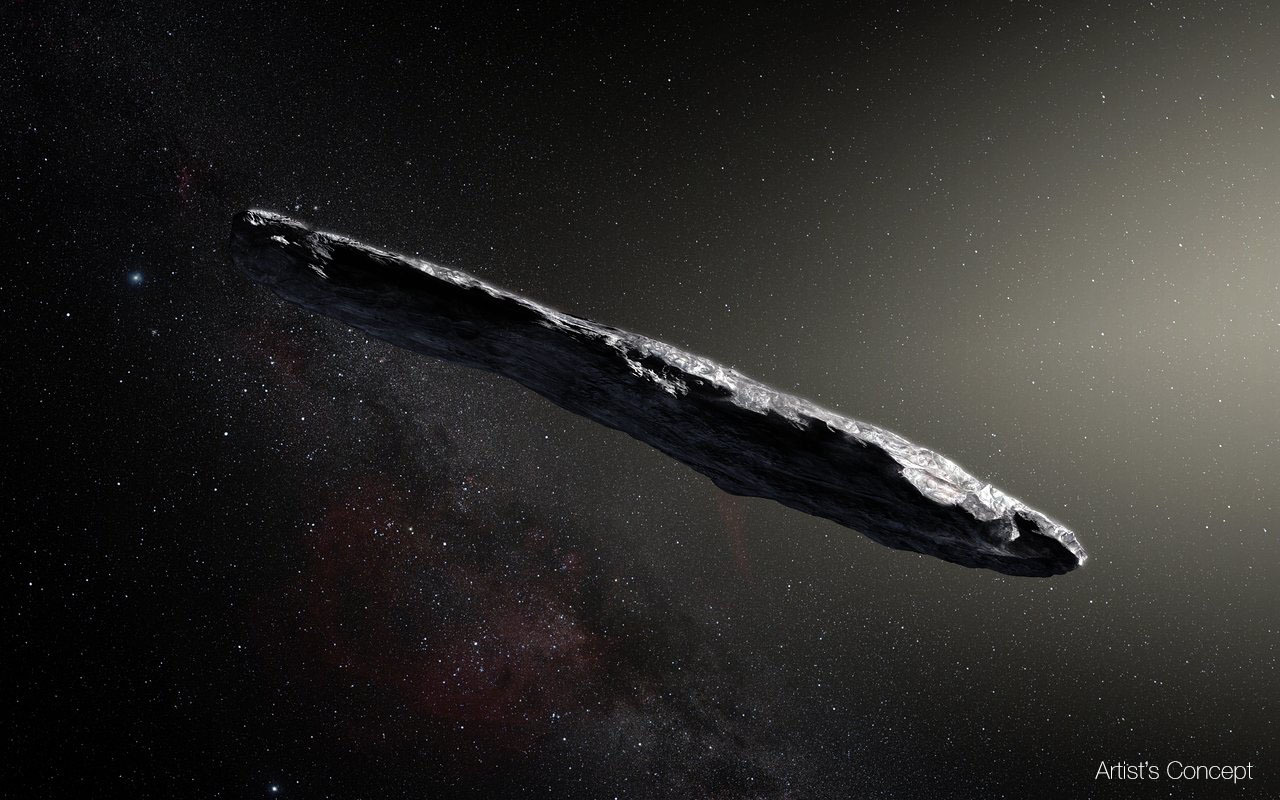

Our solar system's first known interstellar visitor is likely even more alien than previously imagined, a new study suggests.

The mysterious, needle-shaped object 'Oumuamua, which was spotted zooming through Earth's neighborhood last October, probably originated in a two-star system, according to the study.

'Oumuamua means "scout" in Hawaiian; the object was discovered by researchers using the Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System (Pan-STARRS), at Haleakala Observatory on the island of Maui. ['Oumuamua: The 1st Interstellar Visitor in Photos]

Astronomers could tell that the 1,300-foot-long (400 meters) 'Oumuamua wasn't from around here based on its hyperbolic orbit, which showed that the object wasn't gravitationally bound to the sun. Initially, scientists thought the body was probably a comet. But 'Oumuamua displayed no cometary activity — no long tail, no cloud-like "coma" around its core — even after getting relatively close to the sun, so it was soon reclassified as an asteroid.

"It's really odd that the first object we would see from outside our system would be an asteroid, because a comet would be a lot easier to spot, and the solar system ejects many more comets than asteroids," study lead author Alan Jackson, a postdoctoral researcher at the Centre for Planetary Sciences at the University of Toronto Scarborough, said in a statement.

But 'Oumuamua probably didn't come from a system like our own, according to the new study. Jackson and his colleagues performed computer-modeling work, which indicated that systems with two close-orbiting stars boot out asteroids much more efficiently than one-star systems do.

And there are a lot of these binary systems out there; previous research has suggested that more than half of all Milky Way stars have close stellar companions.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Nobody knows for sure where 'Oumuamua came from or how long it's been voyaging through deep space. But the odds are good that it was born into a binary system that harbors at least one big, hot star, according to the new study. That's because such systems are likely to have predominately rocky (as opposed to icy) bodies orbiting relatively close in, in the prime ejection zone.

And 'Oumuamua was likely booted out during its natal system's planet-formation period, however long ago that may have been, Jackson and his team said.

'Oumuamua made its closest approach to Earth — about 15 million miles (24 million kilometers) — on Oct. 14. The object is now barreling toward the outer solar system and has been too distant and faint to study even with large telescopes since mid-December, NASA officials have said. But astronomers gathered a slew of data about 'Oumuamua while they could, and they will doubtless be mining this information for a long time to come.

"The same way we use comets to better understand planet formation in our own solar system, maybe this curious object can tell us more about how planets form in other systems," Jackson said.

The new study was published today (March 19) in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.