Is the James Webb Space Telescope 'Too Big to Fail?'

Any way you slice it, NASA's James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is one of the boldest, highest-stakes gambles in the space agency's storied history. Just building and testing the observatory has proved to be a dauntingly complex technological enterprise, pushing the observatory's astronomical price tag to nearly $9 billion and requiring participation from the European and Canadian space agencies. JWST is both a barrier-breaking and budget-busting undertaking.

Conceived in the late 1980s as a way to peer back over 13.5 billion years of cosmic history to see the faint infrared light from the universe's very first stars and galaxies, JWST today is being tasked with an ever-growing menu of other scientific duties. Scientists now see its stargazing power, which by some metrics is 100 times greater than that of the famed Hubble Space Telescope, as a promissory note: The future of practically every branch of astronomy will be unquestionably brightened by JWST's successful launch and operation. But due to its steadily escalating cost and continually delayed send-off (which recently slipped from 2018 to 2019), this telescopic time machine is now under increasingly intense congressional scrutiny.

To help satisfy any doubts about JWST's status, the project is headed for an independent review as soon as January 2018, advised NASA's science chief Thomas Zurbuchen during an early December congressional hearing. Pressed by legislators about whether JWST will actually launch as presently planned in spring of 2019, he said, "at this moment in time, with the information that I have, I believe it's achievable."

'We Can't Go Out and Fix It'

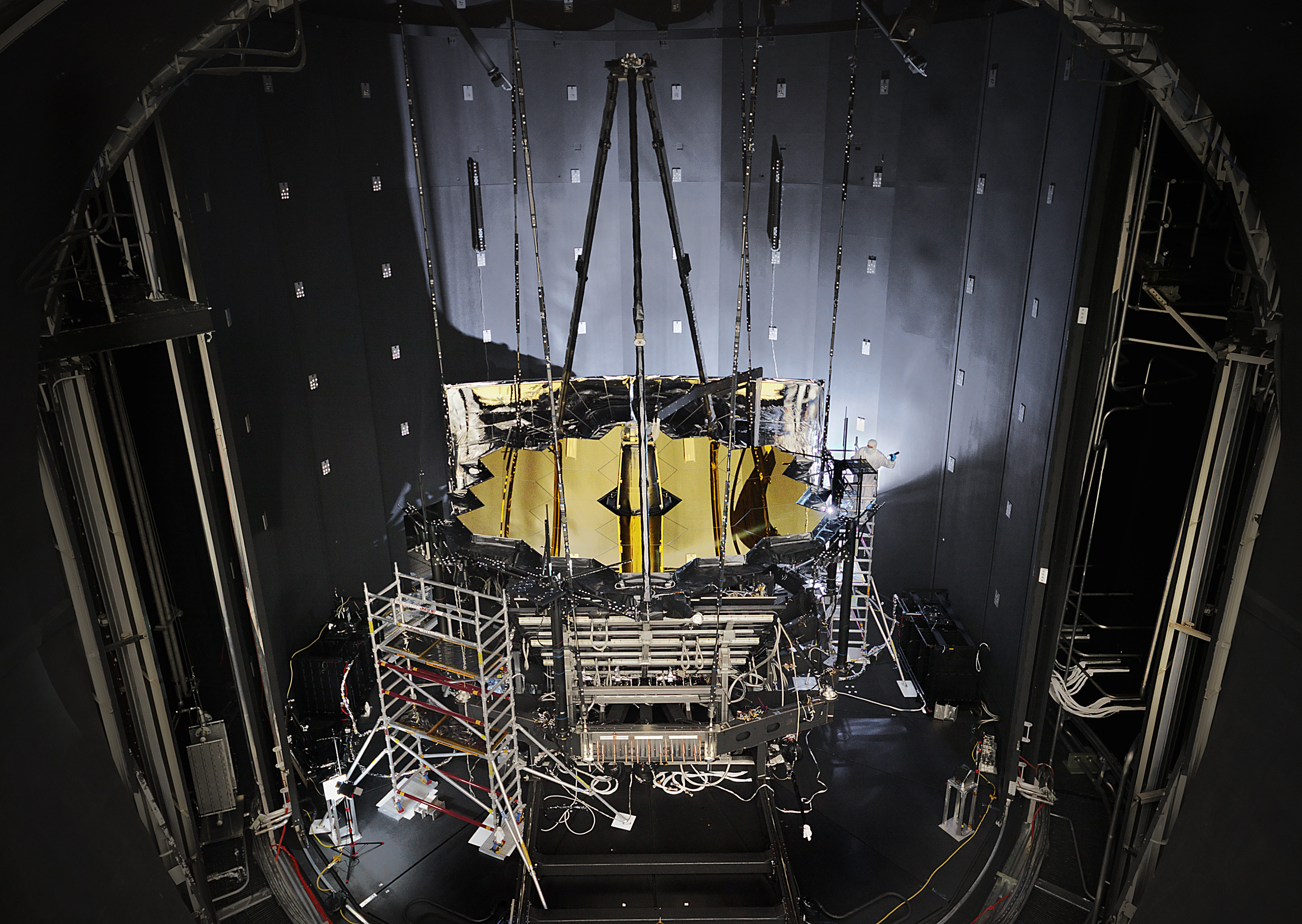

JWST's eagle-eyed astronomical acumen stems from its gigantic 6.5-meter primary mirror. Composed of 18 gold-coated hexagons forged from featherweight beryllium, the mirror is taller than a four-story building, and once launched will be the largest ever flown in space. Carrying science instruments to detect very faint infrared sources, the observatory must operate at ultra-cold temperatures requiring a multi-layered tennis-court-sized "sunshield" to insulate it from the Sun's heat.

Now toss in for good measure where in space JWST will reside. After launching on Europe's Ariane 5 rocket from French Guiana and following roughly 100 days of space travel, the observatory will be parked one million miles away from Earth, far beyond the orbit of the moon. It will reside within the Earth-Sun Lagrange point, or L2, a locale where the collective gravitational tugs of the Earth, Sun and moon allow the telescope to stay aligned with our planet as it moves around our star. Out there—way, way out there—JWST's operators will remotely test and tweak the observatory with commands beamed from Earth, bringing it fully online and ready for science within six months of its launch.

But, first things first: Simply launching JWST is fraught with peril, not to mention unfurling its delicate sunshield and vast, segmented mirror in deep space. Just waving goodbye to JWST atop its booster will be a nail-biter.

"The truth is, every single rocket launch off of planet Earth is risky. The good news is that the Ariane 5 has a spectacular record," says former astronaut John Grunsfeld, a repeat "Hubble hugger" who made three space-shuttle visits to low-Earth orbit to renovate that iconic facility. Now scientist emeritus at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, he sees an on-duty JWST as cranking out science "beyond all of our expectations."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Assuming we make it to the injection trajectory to Earth-Sun L2, of course the next most risky thing is deploying the telescope. And unlike Hubble we can't go out and fix it. Not even a robot can go out and fix it. So we're taking a great risk, but for great reward," Grunsfeld says.

There are, however, modest efforts being made to make JWST "serviceable" like Hubble, according to Scott Willoughby, JWST's program manager at Northrop Grumman Aerospace Systems in Redondo Beach, California. The aerospace firm is NASA's prime contractor to develop and integrate JWST, and has been tasked with provisioning for a "launch vehicle interface ring" on the telescope that could be "grasped by something," whether astronaut or remotely operated robot, Willoughby says. If a spacecraft were sent out to L2 to dock with JWST, it could then attempt repairs—or, if the observatory is well-functioning, simply top off its fuel tank to extend its life. But presently no money is budgeted for such heroics. In the event that JWST suffers what those in spaceflight understatedly call a "bad day," whether due to rocket mishap or deployment glitch or something unforeseen, Grunsfeld says there's presently an ensemble of in-space observatories, including Hubble, and an ever-expanding collection of powerful ground-based telescopes that would offset such misfortune.

"The loss of a major spaceborne observatory would be a real tragedy, but I suspect we would recover quickly," contends Grunsfeld. "With or without JWST, it's going to be a Golden Age of astronomy," he says.

Boosterism

During the December congressional hearing on JWST and other future NASA space telescopes, Space Subcommittee chairman Brian Babin (R-Texas) questioned the decision to send JWST to space by way of the Ariane 5 rocket "instead of a reliable U.S. launch vehicle." He also asked about the risks associated with transporting the telescope to the European launch site in South America.

When asked by Scientific American, two senior members of NASA's JWST team provided assurances. Jon Lawrence, JWST mechanical systems lead engineer/launch vehicle liaison at NASA Goddard and Eric Smith, program director and program scientist for JWST at NASA headquarters, jointly offered a carefully optimistic take.

JWST "will launch on the stable, reliable Ariane 5 with 81 consecutive successful flights over nearly 15 years," they explain. Moreover, there is "robust insight" provided by a combination of frequent direct interactions between the JWST team and the booster's operator, Arianespace, a French launch company. That relationship is further supplemented by ongoing advisory support from other parts of NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA).

"Through a more than 14-year partnership, JWST has developed a strong relationship with ESA and Arianespace, with leadership personnel maintaining long-term stability," Lawrence and Smith explain. This "gives NASA confidence that all launcher issues of interest will be thoroughly and adequately addressed for JWST prior to launch," they note.

The Blame Game

JWST coming to a fiery end due to a booster malfunction at launch or freezing to death after failed deployment at L2 stirs up deep, dark nightmares for scientists. For astronomers who have planned the long-term future of their field around the telescope's success, its loss would be akin to a cosmological cardiac arrest.

"The consequences are almost too horrific to imagine," says Jack Burns, professor of astrophysics and planetary science at the University of Colorado, Boulder. "The thought of over $8 billion of taxpayer funding being lost [would] have potential dire consequences for NASA and for astrophysics. There [would] be multiple committee hearings on Capitol Hill and independent panels assembled to investigate," he says.

Those investigations, Burns says, would follow a long and winding road of accusations and denials that would be made all the worse by the absence of JWST's foremost congressional champion, Barbara Mikulski, a veteran Democratic senator from Maryland who recently retired from public service.

"So, the finger pointing [could] be ugly," Burns says. "Depending upon the nature of the failure, contractors [would] have difficulty in winning new space-science mission contracts and managers at NASA [could] be taking early retirement." Once the telescope is up and running, JWST's massive "budget wedge" (the amount of year-to-year money it requires) will shrink, and those freed-up funds would then support NASA's next large telescope project. An observatory dud after nearly $9 billion of expenditures could very well mean a financial disappearing act for huge portions of NASA's science budget, potentially jeopardizing planning for JWST's successors, Burns says.

"The ripple effect [would] likely be felt for a decade as the community attempted to rebuild our credibility with the Congress and the public," Burns says. "So, failure is not really an option—or, as we heard during the Great Recession, JWST is 'too big to fail.'"

That said, NASA and its myriad contractors have worked hard over the past decade to test and re-test JWST's components, Burns attests. "The management over the program is much better in the past five years than it was previously. If this current delay [to 2019] results in burning through the remaining [budget] reserves but helps guarantee success, then this is the right decision," Burns says.

Further Delays Ahead?

Increasingly, however, there are rumblings that JWST may not even make its planned launch in 2019. During December's congressional hearing, Thomas Young, a former director of NASA Goddard and a member of the National Academies Committee on Astronomy and Astrophysics said JWST could still experience further disruptions.

"The current assessment of JWST's status is that integration and [testing] will take significantly longer than planned," Young testified. "The result is a launch schedule delay and the consumption of most of the remaining funding reserves. In my opinion, the launch date and required funding cannot be determined until a new plan is thoughtfully developed and verified by independent review." At that same hearing, Cristina Chaplain, director of acquisition and sourcing management for the U.S. Government Accountability Office–a federal budgetary watchdog group–underscored JWST's significant cost increases and schedule delays. Prior to being approved for development, Chaplain noted, JWST's cost estimates ranged from $1 billion to $3.5 billion, with expected launch dates varying from 2007 to 2011.

Chaplain noted that the price tag for building, launching and operating the telescope is now estimated to tally nearly $9 billion.

While JWST continues to make progress toward launch, Chaplain warned the program is encountering technical challenges that require both time and money to fix and may lead to additional delays. "Given the risks associated with the integration and test work ahead, coupled with a level of schedule reserves that is currently well below the level stated in the procedural requirements issued by the NASA center responsible for managing JWST, additional delays to the project's revised launch readiness date of June 2019 are likely," she stated in written testimony.

On Track, For Now

JWST's final stage before being shipped to its launch site will occur at Northrop Grumman in California. Last October, company engineers there deployed the telescope's five-layered sunshield subsystem at full tension for the first time.

Additionally, in November, the telescope's combined science instruments and optical elements — including those 18 special lightweight beryllium mirrors—completed about 100 days of rigorous testing within a large chamber at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. Those tests mimicked the cold and vacuum of space to certify the hardware will work properly once on location at Lagrange point 2.

While the march to launch of JWST is underway, still ahead is the final integration phase where the instruments and telescope are united with the spacecraft and sunshield to form the whole, completed observatory. The telescope is now entering its riskiest phase of development, a time when issues are likely to crop up and schedules could slip. Tensions surrounding this risky and costly enterprise are as high as the tautness of JWST's spring-loaded multilayered sunshield. The chance for failure may be low, but its cost could prove catastrophic. Then again, few ever assumed plying the universe for its deepest secrets would come cheaply.

This article was first published at ScientificAmerican.com. © ScientificAmerican.com. All rights reserved.

Follow Scientific American on Twitter @SciAm and @SciamBlogs. Visit ScientificAmerican.com for the latest in science, health and technology news.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.