In Order for Asteroid Mining to Become a Reality, We'll Need Better Telescopes

The idea of mining asteroids for precious mineral deposits has gained steam in recent years, with space mining startups focusing on logistics and governments like Luxembourg positioning themselves as big funders of the sector.

But before we go asteroid mining, we need to figure out where to look — and we don't have the telescopes available to do proper surveys, according to a new white paper that was discussed this week at a conference in Latvia.

The paper was presented at the European Planetary Science Congress in Riga, Latvia. It arose from a 2016 conference, called the Asteroid Science Intersections with In-Space Mine Engineering (ASIME), which brought together engineers and asteroid scientists to discuss the best approaches for mining.

"Asteroid mining is this incredible intersection of science, engineering, entrepreneurship and imagination," said J.L. Galache, the lead author of the paper and cofounder and chief technology officer of Aten Engineering, in a statement. "The problem is, it's also a classic example of a relatively young scientific field in that the more we find out about asteroids through missions like Hayabusa and Rosetta, the more we realize that we don't know."

RELATED: Using Astronomy to Prospect for Asteroids Could Help Us Mine the Heavens

The first asteroid was discovered in 1801 — the small world of Ceres, which was later reclassified as a dwarf planet. While there are millions of these small bodies floating around the solar system, it is near-Earth objects — the ones that come closest to Earth — that are best for mining, since it takes little fuel or time to reach these asteroids. So far, NASA tracks roughly 16,700 near-Earth objects.

Only a handful of spacecraft have been close to an NEO, however, so we need to classify their resources through telescopes. Useful resources include water and fuel, which some space advocates say could be mined at low cost to explore other planets. It's possible to do this through spectral information, which yields the composition of the asteroid.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But Galache says there aren't enough telescopes available to do searches at the right time. Several entities have early-stage plans to view and classify asteroids using telescopes, including the companies Deep Space Industries and Planetary Resources, and the non-profit B612 Foundation — but these aren't ready yet.

"NEOs are usually discovered when they are at their brightest, so our best chance of studying them is by immediately following up detections with further observations to characterize their shape and spectral properties," he said. "That needs good quality, relatively large, dedicated telescopes that are available at short notice. We don't have reliable access to these facilities right now."

RELATED: Future Asteroid Miners Seek Solid Space Rock Plan

Even with the right telescopes, other considerations are necessary to make asteroid mining a reality. Some of the other problems Galache's group identified include understanding more about how regolith (soil) behaves in the low gravity of an asteroid, creating better regolith simulants on Earth to design mining equipment, and learning about the abundance of elements on different types of asteroids in our solar system. More observation is needed because past missions to asteroids have shown that each of the ones analyzed have looked so different.

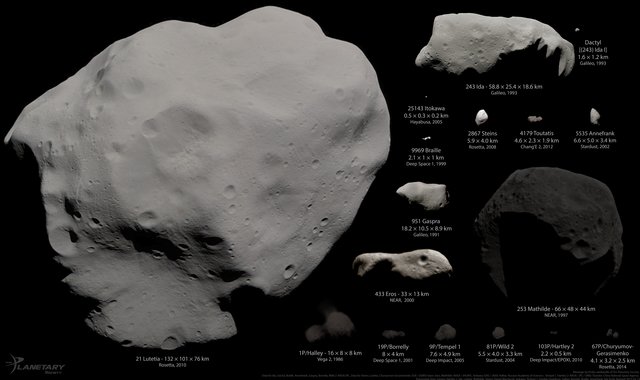

For example, NEAR Shoemaker’s observations of the asteroid Eros showed a fine layer of dust on the surface. By contrast, Hayabusa's observations of Itokawa revealed blocks that are tens of inches in diameter. The recent Rosetta mission, which studied Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko, also found that the surface of the comet is denser than its insides, but it's unclear if asteroids possess the same properties.

While asteroid mining is decades away, there are a couple of spacecraft on their way to asteroids to do more up-close observations and bring samples back to Earth. NASA's Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, Security, Regolith Explorer (OSIRIS-REx) mission is on its way to asteroid Bennu and will arrive in 2018. Meanwhile, Japan's Hayabusa 2 will reach asteroid Ryugu in 2020.

Originally published on Seeker.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.