Why Did A Meteor Shower Seem to Vanish for Decades? Scientists May Finally Know Why

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The fate of a meteor shower that seemed to disappear after the 1950s may have been uncovered by a group of Japanese scientists.

The Phoenicid meteor shower (named after the constellation Phoenix) was first observed in Dec. 5, 1956, over the Indian Ocean by the first Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition, according to a statement from the Japanese National Institutes of Natural Sciences. The space rocks that streamed through Earth's atmosphere appeared to originate from the constellation Phoenix.

But the December Phoenicids haven't been seen since 1956. Now, Japanese scientists think they know why. [How to See the Best Meteor Showers of 2017]

Meteor showers occur when Earth passes through a stream of space rocks usually created by a comet circling the sun, which is why most meteor showers occur about the same time each year. (There is another Pheonicid meteor shower that takes place in July that is not related to the December Pheonicids.)

The researchers gathered evidence tying the December Phoenicids to the Comet Blanpain. The comet was first identified in 1819, according to the paper, but was lost from astronomical records until 2003, when a group of researchers found a smaller space rock (without the signature "tail" of a comet) moving along Blanpain's orbit. It's likely that the comet broke apart, leaving behind the smaller body (which the research say should be considered an asteroid, not a comet) and a trail of dust.

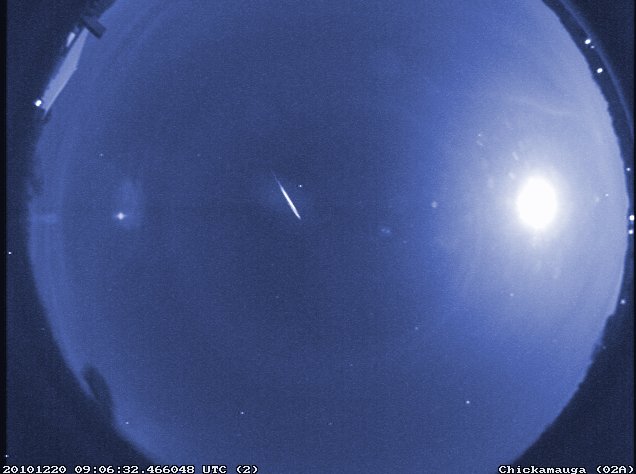

If Blanpain were responsible for the lost Pheonicid meteor shower, then the researchers believed the remaining dust trail should still create a meteor shower. They tested their hypothesis on Dec. 1, 2014. Two observation teams gathered data on the meteors that appeared that night, and traced the paths of the meteors back to their source.

The researchers identified 29 meteors as Phoenicids (out of 138 total observed that night), and the meteor shower peaked within an hour of the predicted time. Those results seem to support the hypothesis, but the authors note that the number of meteors was only 10 percent of what they predicted it would be, which may largely explain why the annual shower was believed to have gone away. The low number of meteors could also tell the researchers more about how much material the original comet was shedding when it created the meteor shower in 1956.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We would like to apply this technique to many other meteor showers for which the parent bodies are currently without clear cometary activities, in order to investigate the evolution of minor bodies in the solar system," said Yasunori Fujiwara, a graduate student at the Department of Polar Science, SOKENDAI (The Graduate University for Advanced Studies), who led one of the observing teams.

Fujiwara's results are being published in the Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan. The results from the second observing team will appear in the journal Planetary and Space Science.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter