Juno Jupiter Probe Won't Move into Shorter Orbit After All

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

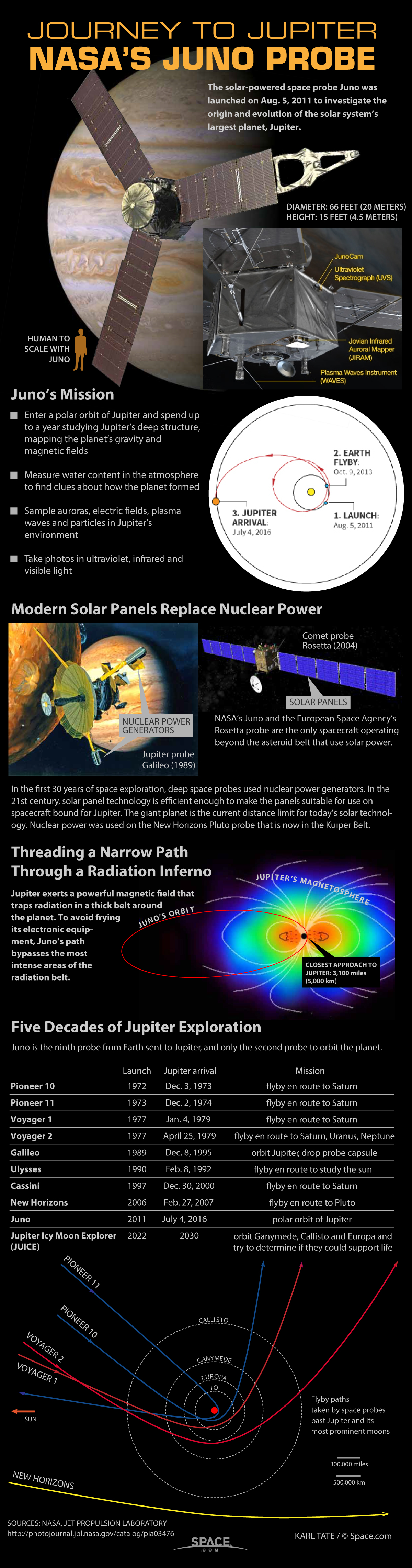

NASA's Juno spacecraft won't move into a closer orbit around Jupiter as originally planned, agency officials announced today (Feb. 17).

Juno slipped into a highly elliptical, 53-Earth-day-long orbit around Jupiter when it arrived at the giant planet on July 4, 2016. The probe was supposed to perform an engine burn in October to reduce its orbital period to 14 days, but an issue with two helium valves postponed that maneuver.

The engine burn has now been canceled, meaning Juno will stay where it is through the end of its mission. [Photos: NASA's Juno Mission to Jupiter]

"During a thorough review, we looked at multiple scenarios that would place Juno in a shorter-period orbit, but there was concern that another main engine burn could result in a less-than-desirable orbit," Rick Nybakken, Juno project manager at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, said in a statement. "The bottom line is, a burn represented a risk to completion of Juno's science objectives."

The $1.1 billion Juno mission launched in August 2011 to study Jupiter's magnetic and gravitational fields, composition and interior structure. The spacecraft gathers most of its relevant data during close flybys that bring it as near as 2,600 miles (4,200 kilometers) to Jupiter's cloud tops.

The original mission plan, with an elliptical 14-day orbit, called for Juno to perform more than 30 such flybys. In the 53-day orbit, the probe will complete just 12 close encounters, even if it continues operating through July 2018. (That's when the mission's funding is currently scheduled to run out, though the Juno team may end up applying for a mission extension.)

But Juno should still be able to accomplish its mission goals in the longer orbit, NASA officials said. In fact, the 53-day path will allow the probe to perform some "bonus science" in the outer regions of Jupiter's magnetosphere, they added.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Another key advantage of the longer orbit is that Juno will spend less time within the strong radiation belts on each orbit," Juno principal investigator Scott Bolton, of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, said in the same statement. "This is significant because radiation has been the main life-limiting factor for Juno."

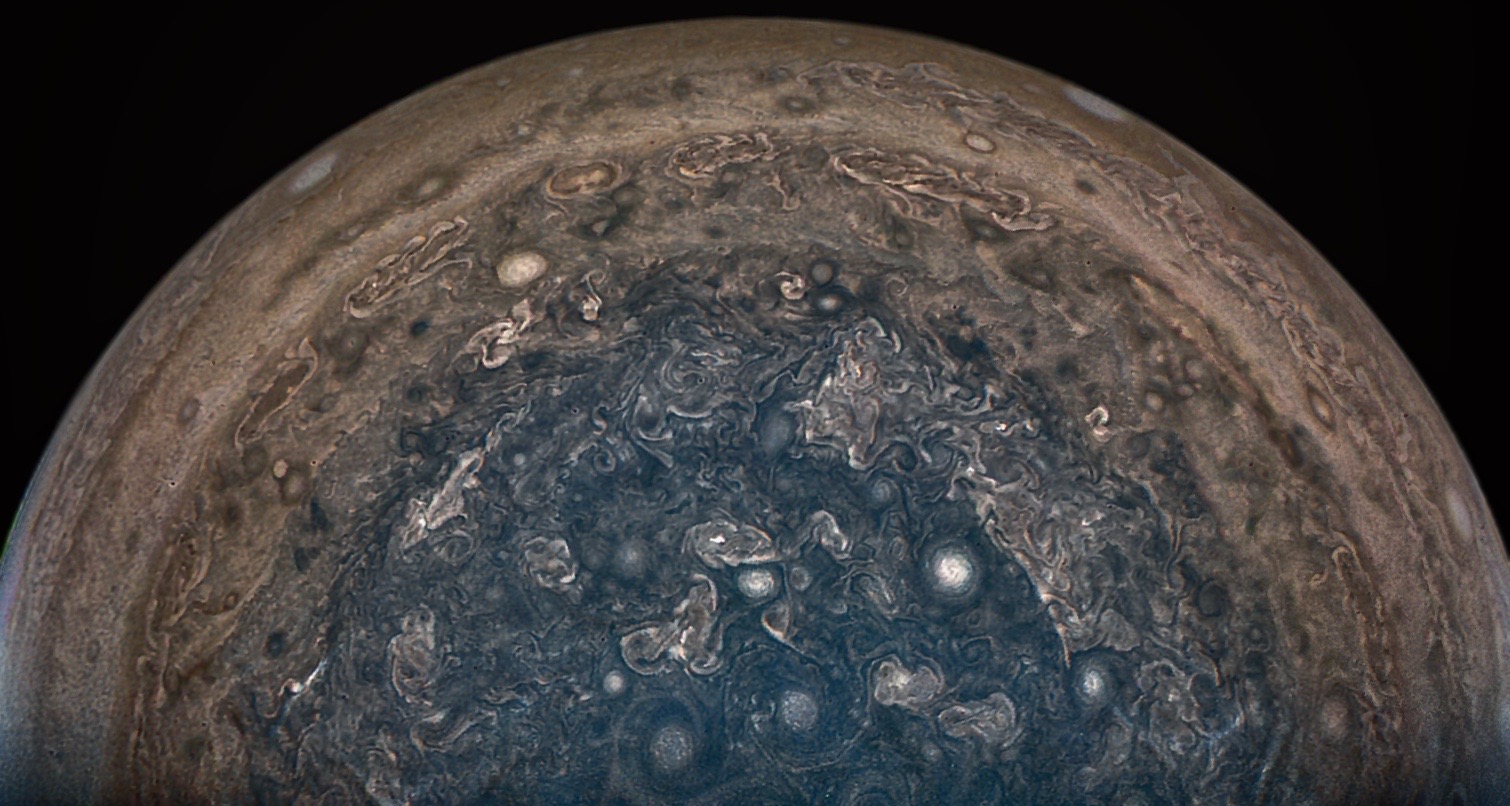

Juno has conducted four close flybys since arriving at Jupiter — on Aug. 27, Oct. 19, and Dec. 11, 2016, and Feb. 2, 2017. These encounters have already revealed that Jupiter's magnetic field and auroras are more powerful than scientists had thought, and that the bands and belts visible at the planet's cloud tops actually extend deep into the interior.

"Juno is providing spectacular results, and we are rewriting our ideas of how giant planets work," Bolton said. "The science will be just as spectacular as with our original plan."

Juno's next flyby will take place March 27.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.