How Do You Age a Star? Check Its 'Heartbeat' (Video)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Watching the "heartbeat" of young stars could help researchers more precisely determine the stars' ages, which in turn would reveal insights about how they are born and age, a new study reports.

Stars form in massive clouds of gas, contracting and growing hotter until they fuse hydrogen in their cores. (That nuclear furnace is what continues to power Earth's sun, some five billion years after it was born.)

It's hard to observe newborn stars inside their gas clouds until they get to a certain size and age, blowing the gas away from themselves. That means it's tough to pinpoint their ages. But now researchers say there could be a way to do this by observing variable stars. [Top 10 Star Mysteries of All Time]

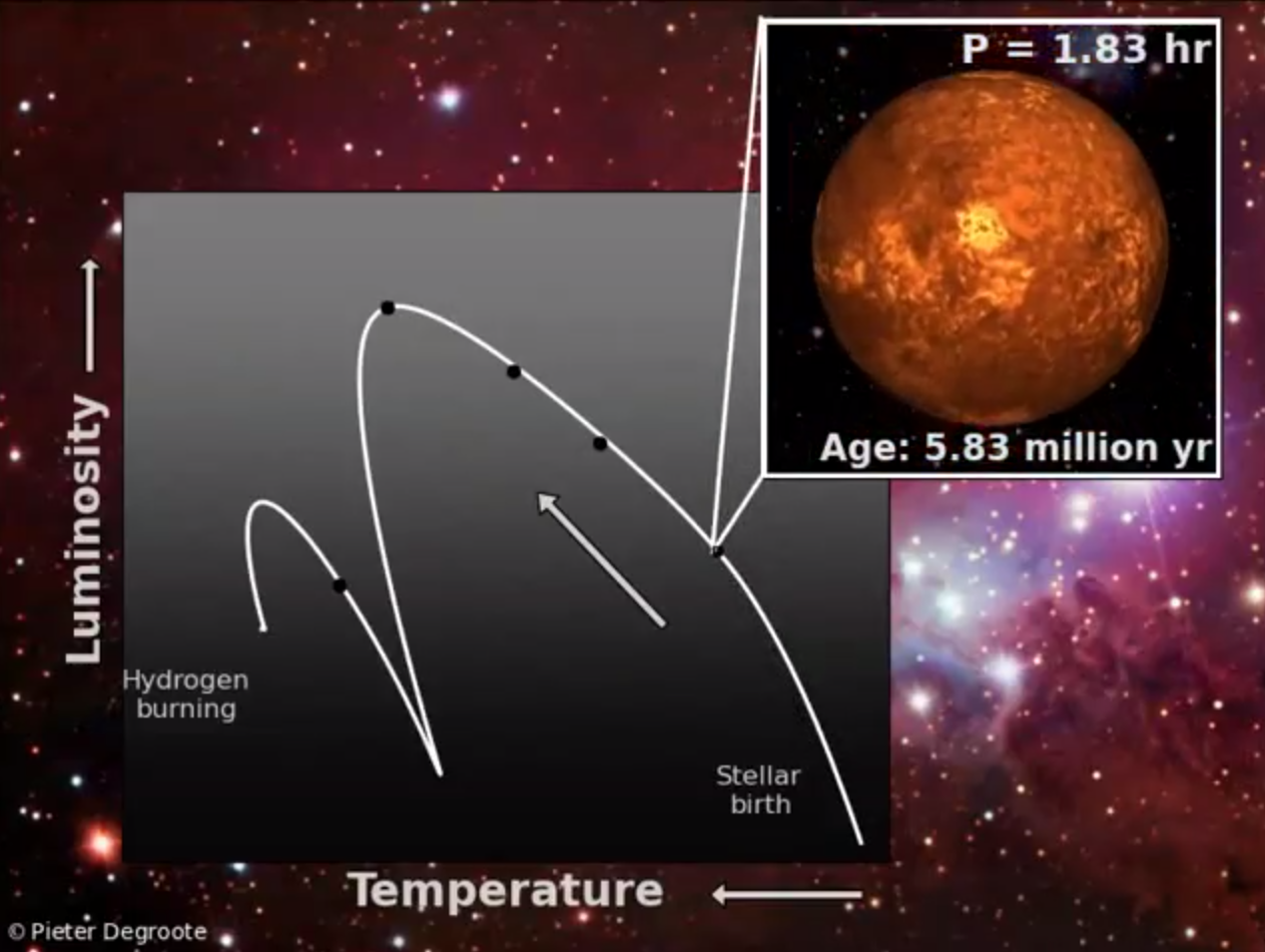

Unlike the Earth's sun, variable stars change their luminosity over time, either regularly or irregularly. The researchers discovered that the youngest of these stars — the ones that haven't fused hydrogen yet — tend to pulse more slowly than those that just started hydrogen fusion.

Why this is so remains unclear, but scientists suppose that as the star gets smaller, its "heartbeat" speeds up.

Aging stars more accurately

The study team looked at 34 well-characterized young stars that are considered "intermediate" in size, meaning they are about 1.5 to 4 times the mass of the sun. All have surface temperatures that average 12,140 degrees Fahrenheit to 13,940 degrees Fahrenheit (6,725 degrees Celsius to 7,725 degrees Celsius). Their periods of variability range between 15 minutes and five hours.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

All of these stars are variable because of their internal structure; something within is making their energy pulse outward and then bound in again. (Other stars can be variable — for example, if they are orbiting in a pair — but these were not a part of the study.)

In this sample, the researchers discovered a correlation between the stars' age and variability. Lead researcher Konstanze Zwintz, a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Leuven in Belgium, said more work needs to be done to generalize the findings. It's not clear now if the same relation exists in larger stars, for example.

One high-priority future goal would be to reduce the error bars in figuring out the age of young stars. While astronomers can generalize the age of stars by looking at those that are born in clusters (this makes for easy comparisons), if the group is considered five million years old with an accuracy of plus or minus five million years, it makes age hard to determine.

"We're not at that stage yet," Zwintz told Space.com, explaining that the uncertainty for a cluster that is five million years old is significant, compared to another that might be 100 million years old.

Tough to observe

The young stars are not only hard to observe, but there are also few telescopes dedicated to examining these stars' variability, Zwintz pointed out.

Half of the stars were observed using the 10-year-old Microvariability and Oscillations of STars (MOST) spacecraft. This Canadian satellite is scheduled to shut down in September after the Canadian Space Agency cut its support, saying MOST far exceeded its one-year lifetime and expected scientific output.

But its research team is busily seeking alternatives, MOST principal investigator Jaymie Matthews, an astrophysicist at the University of British Columbia, told Space.com in an email. He's pitching private companies, preparing to talk at a crowdsourcing conference in Alberta and drawing up a NASA proposal. Additionally, Zwintz submitted a 2-million euro ($2.73 million at current exchange rates) European research grant proposal, of which one-tenth would be allocated to operating MOST for almost a year.

The other half of the stars in the new study were observed using both ground observatories and CoRoT (a French acronym meaning Convection, Rotation and planetary Transits). CoRoT, which was also a space observatory, ceased operations in June.

"MOST is the only running operational satellite with the capabilities to observe these stars from space," Zwintz said, but added that ground observatories can perform some of the work. Plus, there are newer space missions that can perhaps fill some gaps.

The new mission for NASA's Kepler spacecraft could point the observatory toward areas with young stars, although it's not clear yet if that will happen, Zwintz said. Other possibilities are the new Bright Target Explorer (BRITE) satellite constellation that examines the brightest stars, or PLATO (Planetary Transits and Oscillations of stars), a European satellite expected to launch in about a decade.

The new study was published online today (July 3) in the journal Science.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or Space.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.