'Satellite Phone' to Record Fiery Death of Japanese Robot Spaceship

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

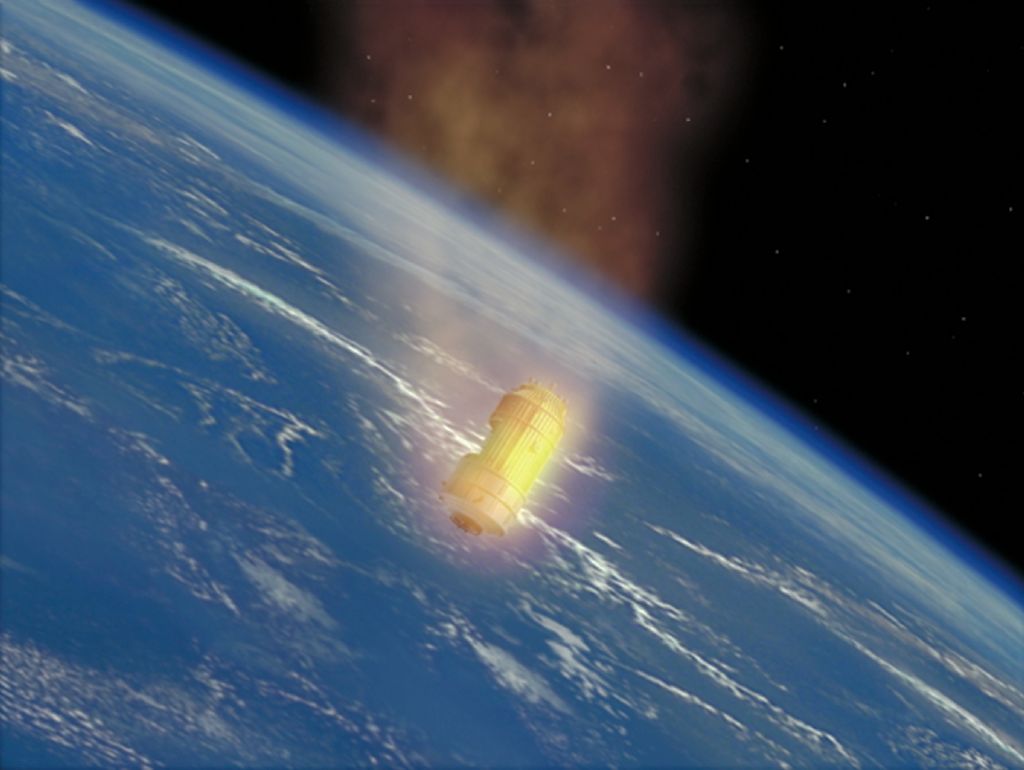

A Japanese robot space cargo ship is carrying a device to "phone home" during its planned death plunge into Earth's atmosphere this week, but the equipment has a more important purpose than calling E.T. for help.

The spacecraft, Japan's unmanned cargo ship Kounotori 2, is due to intentionally burn up tomorrow (March 29 EDT) when it re-enters Earth's atmosphere one day after leaving the International Space Station. In addition to the station trash packed on Kounotori 2, a high-tech sensor is ready to track the finer details of the spacecraft's doom.

In non-sizzle lingo, the Kounotori 2 is carrying a so-called Re-entry Breakup Recorder – or REBR for short – a small and autonomous sensors built to record temperature, acceleration, rotational rate and other data during Kounotori 2's high dive into Earth’s atmosphere.

"REBR is made possible by tiny little instruments, tiny sensors and tiny cell phone technology. It is basically a satellite phone with a heat shield," said William Ailor, Director of the Center for Orbital and Reentry Debris Studies at The Aerospace Corporation in El Segundo, Calif.

Scientists hope the system will record valuable data into how spacecraft are destroyed in the atmosphere.

A similar unit is to be housed within Europe's second Automated Transfer Vehicle (ATV), the ATV-2 Johannes Kepler, which is currently docked at the space station. It, too, will record the death plunge of that unmanned spacecraft when it makes its own fiery plunge to self-destruction later this year.

Recording a spaceship's death

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Kounotori 2 spacecraft is the second H-2 Transfer Vehicle built by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) to ferry tons of supplies and equipment to the International Space Station. It launched in January and arrived at the space station on Jan. 27.

Like other unmanned cargo ships for the space station, the JAXA supply ships are designed to be disposable, but the first ship in the fleet (called HTV-1) did not carry a re-entry sensor when it debuted in 2009.

Each Re-entry Breakup Recorder includes a heat shield to temporarily protect the instrument and data from the scorching hot temperatures of re-entry that will ultimately consume both supply craft.

Two REBRs were launched on Japan's Kounotori 2 vehicle when it blasted off in late January. One of those devices was moved over to the European ATV-2 craft by astronauts on the station and bolted to an internal instrument rack, Ailor explained.

The space station crew is expected to activate Kounotori 2's REBR system before the spacecraft departs the orbiting laboratory today (March 28). The REBR hardware will then look for acceleration rates characteristic of re-entry. Once re-entry is detected, the data recorder collects data from its sensors.

One final "phone call"

While the sensor package on Kounotori 2 will be destroyed like its parent spacecraft, the REBR system is not exactly going down with the ship. [Photos: Spotting Spaceships From Earth]

The system is designed to be released from its host vehicle during the breakup process, and then enter freefall and reach a subsonic speed at about 60,000 feet (18 kilometers). During that last freefall period of about five minutes, the REBR should make a direct dial phone call into the Iridium satellite communications network to dump its recorded data.

The REBR sensor data should then take a secure path to a special website for review by re-entry experts.

"It's all automatic, totally self-contained. It does everything itself and detects when certain things are happening," Ailor told SPACE.com.

Ultimately, the system will crash into the ocean, the 9-pound (4-kilogram) – REBR is not meant to be retrieved – but there is still a lingering question on some scientists' minds: "Will it float?"

"Sure we’d like to get it back," Ailor said, but making it recoverable would make it too costly per unit. "We wanted to make this as inexpensive and benign as possible."

The REBR system was developed over eight years. The project is led by The Aerospace Corporation, with major funding provided by Aerospace, the U.S. Air Force, as well as NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. The heat shield was provided by The Boeing Company and NASA’s Ames Research Center provided in-kind support of the self-stabilizing heat shield design.

Design for demise

Ailor said that the REBR endeavor is to help assess the hazards on the ground from space hardware leftovers that survive re-entry.

"We use computer models developed over the years. But it’s really hard to calibrate and make those models as accurate as you can," Ailor said.

One of the problems re-entry investigators have always battled, Ailor said, “is that it looks like the models don’t quite tell us the truth when we’re trying to predict what’s going to survive … or not.”

REBR is expected to provide specific answers as to when, why and how human-made space objects disintegrate during re-entry.

"Then you can devise spacecraft to come apart in ways which really minimize hazards…sort of a design for demise," Ailor said.

The two REBR flights on Kounotori 2 and the ATV-2 Johannes Kepler are considered proof of concept experiments "to make sure that everything is going to work the way it’s supposed to," Ailor added.

For this first flight, the system's housing is made of copper and designed to release REBR as the temperature of the housing increases.

Interplanetary uses

REBR's first flight test was integrated and is being flown under the direction of the Department of Defense's Space Test Program.

Ailor said "our goal in life is to use external sensors, wireless or wired sensors that would feed information into our device. So we could sprinkle temperature sensors, for example, in the host vehicle … then we would really know when certain key things break apart and leave."

Given successful demonstration of REBR, "I think we won’t have any problems finding rides," Ailor noted. Future applications of the technology, he said, could possibly find their way onto university-built cubesats.

Another idea recently fostered by NASA engineers is using REBR devices on a human mission to Mars.

“Astronauts would throw off a few of these little guys to check atmospheric conditions … maybe plant tiny weather stations around Mars, Ailor said.

"You just never know where it could go," he added.

Leonard David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. He is past editor-in-chief of the National Space Society's Ad Astra and Space World magazines and has written for SPACE.com since 1999.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.