Ginormous Black Hole May Solve Longstanding Mystery

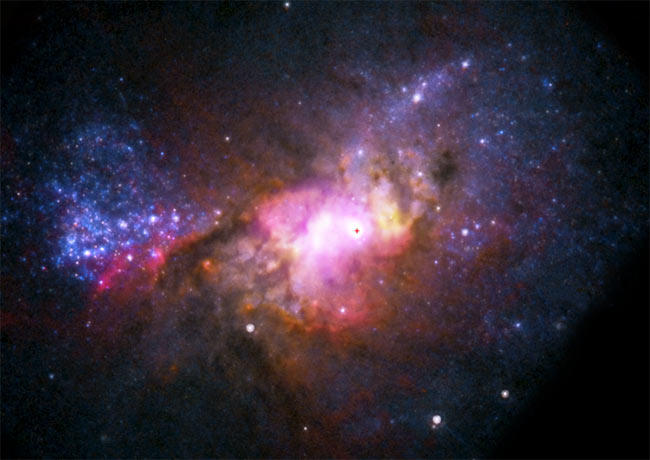

A pipsqueak galaxy nearby that's forming stars at a walloping rate appears to have a ginormous black hole in its center, a new study suggests.

The find is surprising, because dwarf galaxies like this usually don't host supermassive black holes. That this one does could help solve a cosmic conundrum: Which comes first — the black hole or the galaxy?

Many large galaxies — such as our own Milky Way — contain supermassive black holes in their centers. Scientists have wondered if these black holes form initially, and then galaxies build up around them — or vice versa.

The new discovery, of a black hole containing the mass of more than a million suns inside the nearby dwarf galaxy Henize 2-10, finally hints at an answer. [New photo of Henize 2-10]

Bulge-less

Henize 2-10 lacks a bulge — a dense collection of stars that exists at the center of most spiral galaxies. Usually, the mass of a galaxy's bulge directly correlates with the mass of its central black hole. Some researchers thought a galaxy had to already have a bulge before a black hole could form.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"This definitely suggests the black hole comes first, because Henize 2-10 is a very low-mass dwarf galaxy without a detectable bulge, yet it does already have a supermassive black hole sitting there," said study leader Amy Reines, a graduate student at the University of Virginia. "So the implication is you don't have to have a bulge to form a black hole."

Yet more research will be needed to determine if this is the usual case, or if Henize 2-10 is just an oddball.

"This result suggests we need to look at more dwarf galaxies similar to Henize 2-10, because right now we just don't know if this a rare case or if other galaxies like it have their own black holes," Reines told SPACE.com.

Serendipitous discovery

Reines and her colleagues used the National Science Foundation's Very Large Array radio telescope in New Mexico, along with the Hubble Space Telescope, to observe this dwarf galaxy.

The researchers hadn't been looking for black holes, but rather set out to study the furious pace of star formation occurring in Henize 2-10.

"It was a completely serendipitous discovery," Reines said. "I was initially studying the starburst in Henize 2-10 as part of my Ph.D. thesis with no thoughts of black holes."

But while analyzing the data, Reines noticed an abundance of radio waves coming from the center of the dwarf galaxy that looked like what scientists expect when matter falling onto a black hole releases jets of radiation into space.

The researchers compared their observations with photos of the galaxy from the Chandra X-ray Space Telescope, which showed that the same central region was also emitting strongly in X-ray light — another common giveaway of a black hole lurking there.

Reines said her lucky discovery has changed her plans about what she'd like to study in the future.

"For my postdoc work I really want to take a more detailed study of galaxies similar to Henize 2-10 and look hard for other examples like it," she said.

The team's findings were published online Jan. 9 in the journal Nature.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.