Visible Light Spectrum from Alien Planet Measured for 1st Time (Video)

Astronomers have detected an exoplanet's visible-light spectrum directly for the first time ever, a milestone that could help bring many other alien worlds into clearer focus down the road.

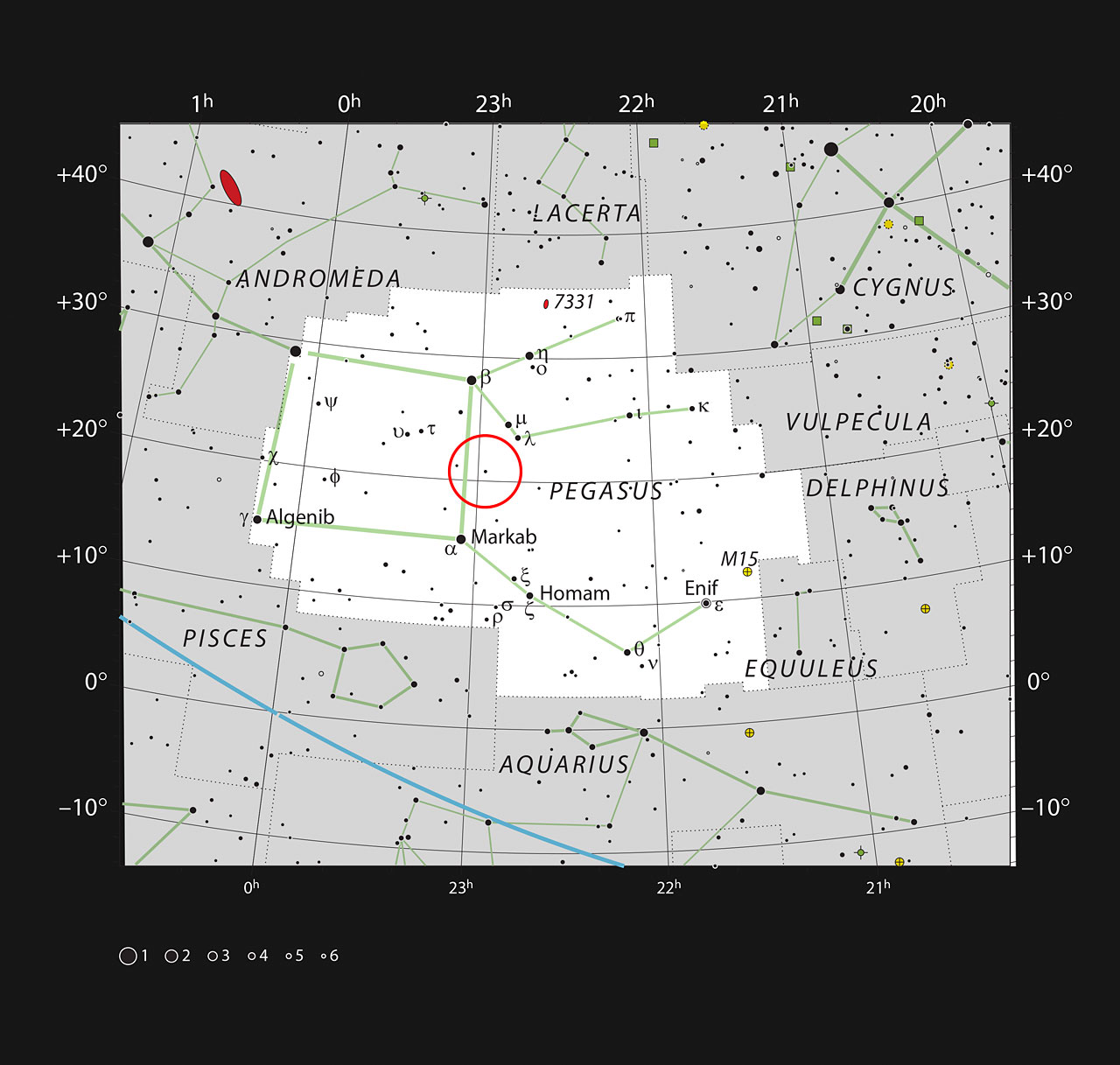

The scientists used the HARPS instrument on the European Southern Observatory's 3.6-meter telescope at the La Silla Observatory in Chile to study the spectrum of visible light reflected off the exoplanet 51 Pegasi b, which lies about 50 light-years from Earth in the constellation Pegasus. You can see a new video of 51 Pegasi b and its environs here on Space.com.

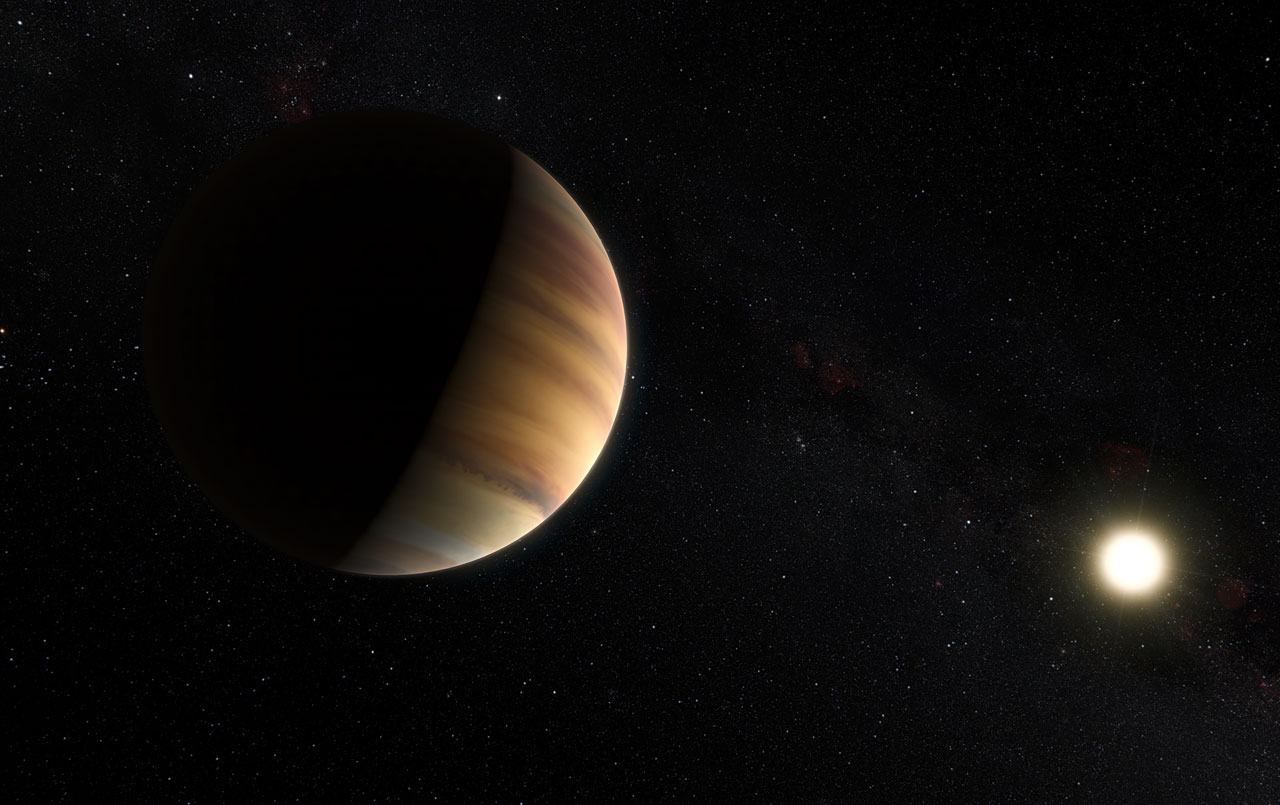

51 Pegasi b, a "hot Jupiter" gas giant that orbits close to its parent star, was spotted in 1995, when it became the first alien world ever discovered around a sunlike star. (The first exoplanets of any type were found in 1992 around a superdense, rotating stellar corpse called a pulsar.) [Gallery: The Strangest Alien Planets]

Researchers most often study exoplanet atmospheres by analyzing the starlight that passes through them when worlds cross their stars' faces from Earth's perspective. This method, known as transit spectroscopy, is restricted to use on systems in which the stars and planets align.

The new strategy used with 51 Pegasi b, on the other hand, does not depend on planetary transits and could thus find broader applicability, researchers said.

The technique offers other scientific advantages as well.

“This type of detection technique is of great scientific importance, as it allows us to measure the planet’s real mass and orbital inclination, which is essential to more fully understand the system," study lead author Jorge Martins, of the Instituto de Astrofísica e Ciências do Espaço (IA) and the Universidade do Porto in Portugal, said in a statement.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"It also allows us to estimate the planet’s reflectivity, or albedo, which can be used to infer the composition of both the planet’s surface and atmosphere," Martins added.

The new data suggest that 51 Pegasi b is highly reflective, a bit larger in diameter than Jupiter and about half as massive as our solar system's biggest planet, researchers said.

The new observations by HARPS (which is short for High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher) provide a vital proof of concept for the new technique, which could really come into its own when employed with instruments on bigger telescopes, such as the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope (VLT), researchers said.

"We are now eagerly awaiting first light of the ESPRESSO spectrograph on the VLT so that we can do more detailed studies of this and other planetary systems,” said co-author Nuno Santos, also of the IA and Universidade do Porto.

The new study was published today (April 22) in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.