Are James Webb Space Telescope images really so colorful?

Do these cosmic objects really look so brilliant?

NASA's James Webb Space Telescope is known for looking deep into the universe with an unprecedented level precision and sensitivity. But its images aren't only scientifically useful — they're also beautiful.

From the blues and golds of the breathtaking Southern Ring Nebula to the pinks, oranges and purples of the Cassiopeia A supernova remnant, James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) images render the universe in brilliant color. The images the orbital observatory produces are often so stunning, you might find yourself asking: Do these cosmic objects really look that colorful? And what would these celestial wonders look like if we could view them with our unaided eyes, instead of on a screen?

As it turns out, scientists aren't exactly sure. "The quickest answer is, we don't know," said Alyssa Pagan, a science visuals developer at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) and a member of the team that helps make JWST images so colorful. But despite the uncertainty, one thing is certain: Your own eyes wouldn't see the universe like this.

If you were somehow able to look directly at these objects with your own eyes, you might see something that resembles the images from telescopes that see the universe visual light, like the Hubble Space Telescope, Pagan said.

But even that comparison isn't quite right, since Hubble is much larger and more sensitive than the human eye, so it can take in much more light. Also, visual-light telescopes might capture different features of an object than an infrared telescope would, even when focused on the same target.

JWST is an infrared telescope, meaning it sees the universe in wavelengths of light that are longer than that of red light, which has the longest wavelength we can detect with our eyes.

How are colors chosen for JWST images?

So how exactly are the colors for the JWST's spectacular images chosen?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The telescope's targets are first observed through several filters that are attached to the telescope. Each filter can "see" in specific ranges of wavelengths of infrared light. JWST's Near Infrared Camera, the telescope's main camera, has six filters, all of which capture slightly different wavelenghts of light. Combining these images into a composite allows Pagan and Joe DePasquale, another science visual developer at the STScI for JWST, to create the full-color images.

When Pagan and DePasquale first receive the images, they appear in black and white. The colors are added to the image later, as the data from the various filters are translated into the spectrum of visible light, Pagan explained. The longest wavelengths appear red, while the shorter wavelengths are blue or purple.

"We are using that relationship with wavelengths and the color of light, and we're just applying that to the infrared," Pagan said.

Once each color has been added to the image, it might go through some additional alterations. Sometimes, the original colors can make an image look faded or dusty, and the colors are made more vivid to give it a sharper quality. The colors might also be shifted to emphasize certain hard-to-spot features.

Pagan and DePasquale also work with researchers to make sure the images are scientifically accurate, particularly if they are presented alongside a particular scientific finding, Pagan said. Though the color images don't provide specific scientific data, they can help illustrate certain findings.

Sometimes they also can help scientists see areas they might want to research, Pagan said. For instance, the most distant objects in JWST's first deep-field view — which appear red because light traveling such a distance had been stretched out — presented targets for research on the early universe when these objects would have existed as they appeared in the deep-field image.

Are JWST images 'real'?

The colors in JWST's images may not be "real," but don't get the wrong idea — the colors aren't meant to trick you, and they aren't chosen simply to make these objects look gorgeous.

Instead, the images are intended to communicate as clearly as possible what JWST can see — and what our eyes can't.

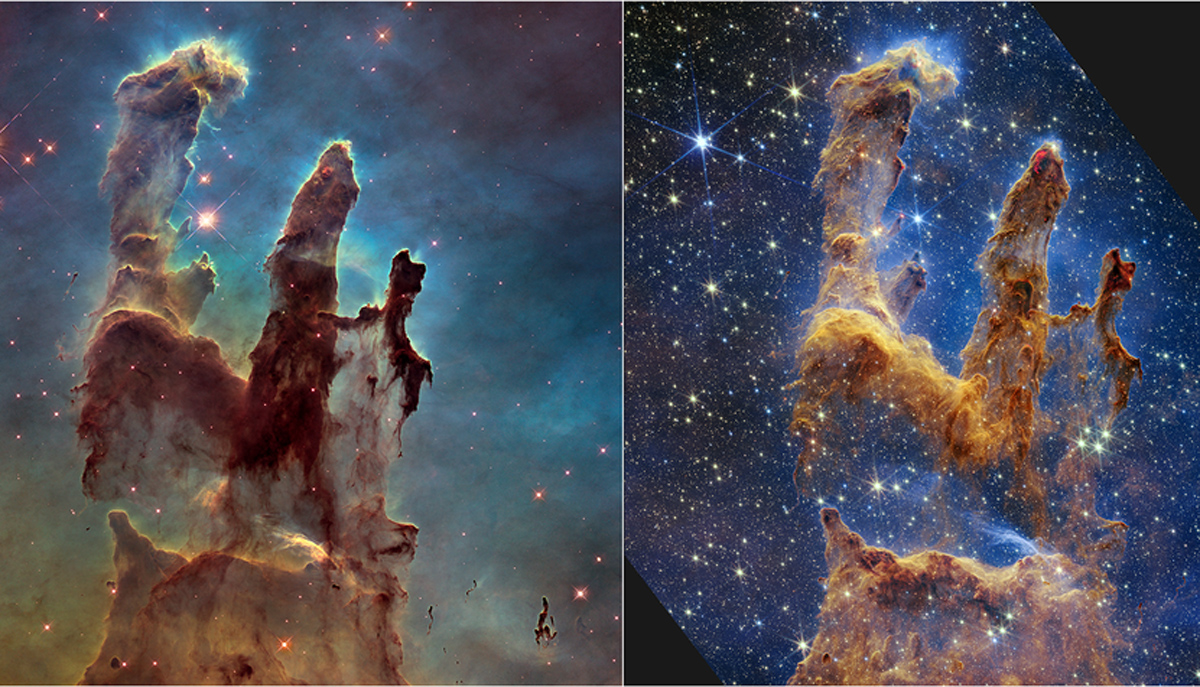

You can see some of the differences between images from visual-light and infrared telescopes by comparing images of the iconic Pillars of Creation taken by JWST and Hubble, seen below.

While large portions of the pillars appear dark red in the Hubble image, the JWST image depicts most of the formation in golden and orange tones. This means that the visual light emitted by the pillars is longer wavelength (red) but a bit closer to the middle of the spectrum of infrared light depicted in the image.

Much of the hazy material that surrounds the pillars in the Hubble image, and even some of the materials of the pillars themselves, is also absent from the JWST image, meaning this portion of gas and dust is transparent in infrared. The JWST image also highlights more areas of star formation in red, which are obscured by thick clouds of gas and dust in the Hubble image.

By adding these colors to the images, scientists help the public appreciate the James Webb Space Telescope and its contributions to astronomy. "We're just trying to enhance things to make it more scientifically digestible and also engaging," Pagan said.

Rebecca Sohn is a freelance science writer. She writes about a variety of science, health and environmental topics, and is particularly interested in how science impacts people's lives. She has been an intern at CalMatters and STAT, as well as a science fellow at Mashable. Rebecca, a native of the Boston area, studied English literature and minored in music at Skidmore College in Upstate New York and later studied science journalism at New York University.