Performing evasive maneuvers increases satellites' collision risk down the road

Our space traffic management efforts need to improve.

Researchers have found that trying to avoid collisions in orbit increases the risk of future collisions in the aftermath of each avoidance maneuver. The reason? Current methods of space traffic management can't adequately deal with the growing numbers of satellites in space.

Analysts with the Pennsylvania-based company COMSPOC (short for "Commercial Space Operations Center") found that, in the aftermath of every satellite collision avoidance maneuver, operators and space traffic observers have only a rough idea of where their objects are.

The difference between an assumed position of a satellite and its actual location can be as large as 25 miles (40 kilometers). As a result, subsequent collision predictions are less than accurate for several days.

"It's hard to plan and to decide what to do and take action when you have such big errors," Dan Oltrogge, COMSPOC's chief scientist, told Space.com.

Related: The worst space debris events of all time

With the growing amount of stuff in orbit — functional satellites and space junk alike — it's easy to see why such uncertainties cause concerns. For example, satellites of SpaceX's Starlink internet megaconstellation had to perform a combined 25,000 collision avoidance maneuvers in the six-month period between Dec. 1, 2022, and May 31, 2023.

Experts think this number likely doubled in the half-year between June 1 and Dec. 1, 2023, as SpaceX continues launching additional Starlink satellites at a steady rate. The constellation now consists of more than 5,100 active satellites, which is less than half of the planned 12,000 satellites of the first-generation Starlink orbital network. But SpaceX has plans to grow its space fleet to more than 40,000 satellites in the future, and other operators have similar ambitions as well.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Soon, satellites orbiting Earth may be forced to perform millions of collision avoidance maneuvers every year. And with inaccurate data rolling in after every such move, devastating crashes could easily occur.

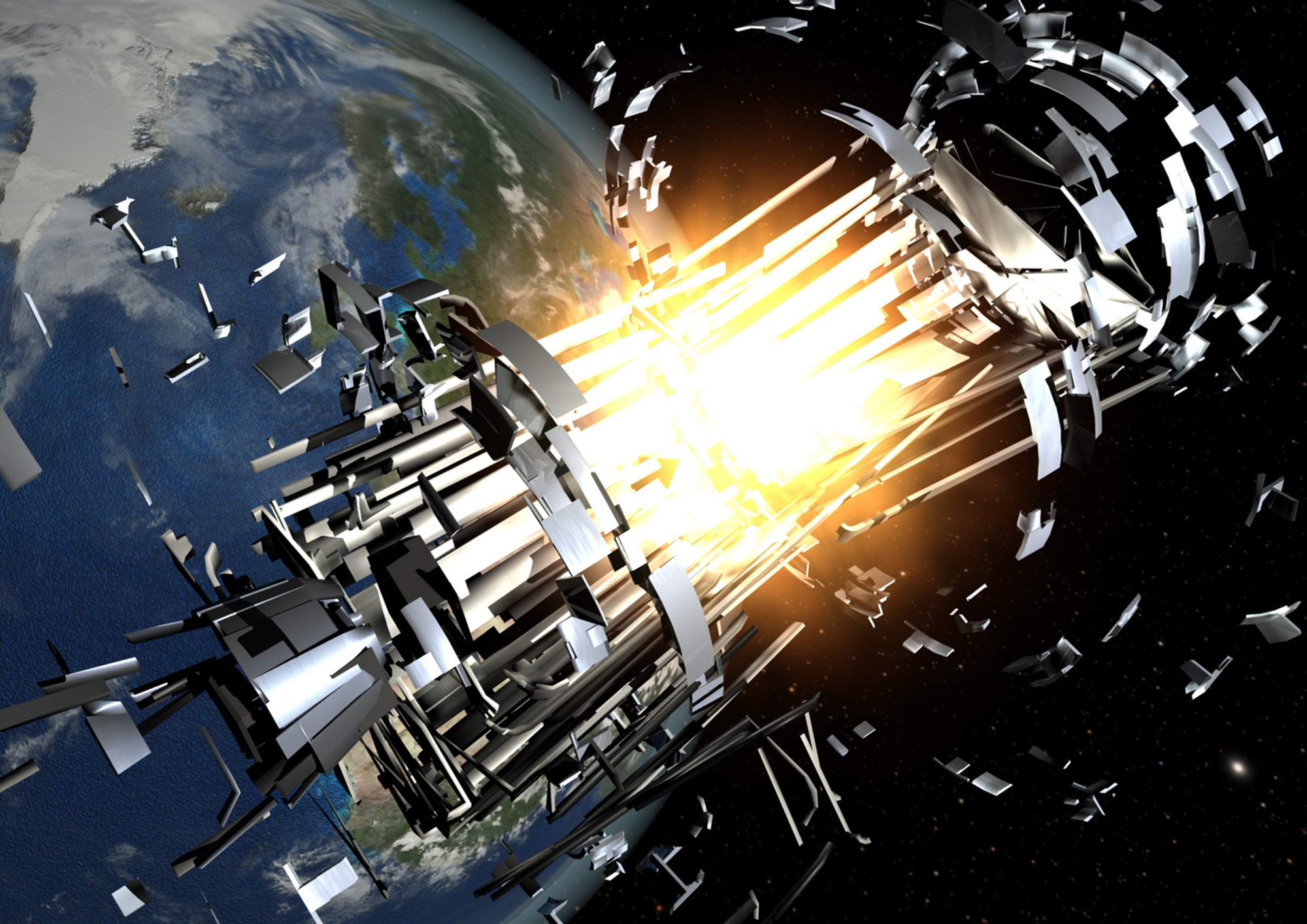

In fact, one such collision has already taken place. According to COMSPOC's recent analysis, the infamous 2009 crash between the U.S. commercial communication satellite Iridium 33 and Russia's defunct Kosmos-2251 happened after Iridium operators instructed their craft to perform two short thruster burns to adjust the satellite's position on the day before the collision. But the U.S. Air Force, at that time responsible for monitoring space traffic, didn't know about these maneuvers and didn't include them in their calculations of Iridium 33's trajectory. The consequences were catastrophic. The collision between the two bodies, each with a mass over 1,540 pounds (700 kilograms), produced thousands of debris fragments, most of which hurtle around Earth to this day.

"The maneuvers themselves weren't known about," said Oltrogge. "When they did the predictions, the models showed a miss distance of about 230 meters [755 feet] during the closest approach and a collision probability of 10-34, which is an extremely small chance of collision."

When COMSPOC analysts included details about the two short thruster burns into their equations modeling the collision, they got a much more serious prediction. Unbeknownst to any of the parties involved at that time, the predicted miss distance dropped to 50 feet (15 m), and the collision probability increased to 1 in 1,000.

Had Iridium operators known about this much higher collision probability back then, they "would definitely [have] take[n] evasive action," Oltrogge said.

Nearly 15 years after that collision — history's second-worst space debris-producing event — mainstream space situation awareness providers still don't routinely incorporate data about satellite maneuvers into their predictions, according to Oltrogge.

But other things have changed since 2009. At the time of that accident, only about 1,000 operational satellites and 15,000 known pieces of space debris orbited Earth. Today, nearly 9,000 functioning spacecraft share the planet's orbit with more than 35,000 tracked pieces of space junk, and millions more pieces of debris too small to monitor.

"Today, we have a much higher chance for collisions," said Oltrogge. "And with all these maneuvers, we see a lot of degradation in our space situational awareness data."

But Oltrogge thinks that a solution to the problem is already available. Commercial companies, including COMSPOC, have developed platforms that can incorporate data about maneuvers obtained from satellite operators. New types of sensors and smart algorithms can further improve accuracy and timeliness of the predictions.

"We have to do better, and we should do so holistically," Oltrogge said. "We should explore many different aspects, including tracking smaller debris and fusing data together and increasing collaboration between satellite operators and space situational awareness data providers."

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.