Wild space 'ferry' concept uses paragliders to return satellites and science to Earth

Outpost recently tested a stratospheric paraglider to return space tech ahead of orbital ventures for NASA and other companies later in the 2020s.

Dropping in twice from a dozen miles high in the stratosphere, a paraglider safely touched down on Earth in a key milestone aimed at removing space debris.

The high-altitude tests in April 2022 were the flying start to Outpost Technologies' vision: to gently return used space hardware back to Earth for reflight or examination. That hardware could be satellites low on fuel, or used-up science experiments on the International Space Station (ISS).

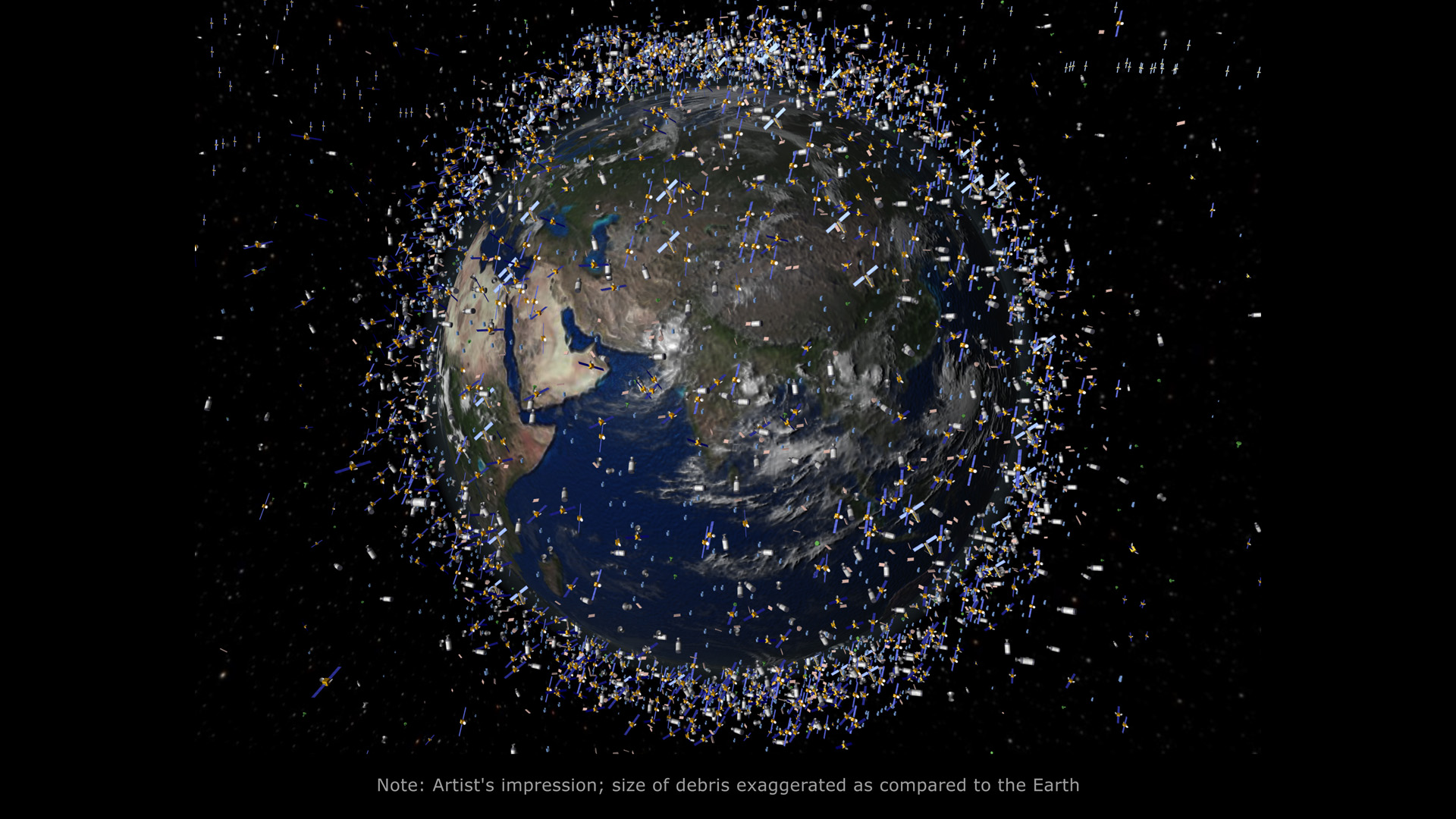

There's an urgent need to help with both industries. Satellites are rapidly cluttering up low Earth orbit and adding space debris that threatens the infrastructure we need for weather forecasts and telecommunications. Meanwhile, the ISS is so crowded with two decades of old experiments and equipment that it is running out of room to host new ones; cargo ships cannot empty it fast enough any more.

Related: Russian space debris forces ISS to dodge, postpones spacewalk

"I believe that what we're what we're developing will basically put an end to space debris," Outpost CEO Jason Dunn told Space.com in December 2022. NASA is paying attention to that: the agency awarded Outpost an early-stage contract on Dec. 6 to design a "Cargo Ferry" version of Outpost's technology targeted for ISS payload return.

Dunn pledges the ferry will be ready long before ISS is scheduled to retire in 2030, to bring home smaller experiments that typically are completed within a few weeks of arriving at the huge complex. Larger payloads would still be flown home on traditional cargo ships, like SpaceX's Dragon, he said.

Dunn knows the ISS through his first major orbital venture, Made In Space, which he founded in 2010. The company is best known for co-producing the first 3D printer for the ISS. Ironically, the printer is still stuck in orbit awaiting a cargo ship slot despite the Smithsonian Institution pledging to take it when it comes home.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The space ferry project was born not only to return hardware like that, but to deal with the ongoing problem of space launching costs and space debris, Dunn said. "As I got more involved in the space industry and my career, a few things were nagging at me ... so much effort, so much money was being put into getting things off the planet, and hardly any effort in getting things back to the planet."

Related: Chinese rocket body disintegrates into big cloud of space junk

Traditionally, Dunn said, we continue to produce throwaway "single mission" items for space that then need to be brought back to Earth. That is slowly changing with the introduction of reusable rocket stages via Blue Origin and SpaceX, and early-stage satellite refueling first demonstrated in-orbit in 2020. But Dunn said more should be done, which inspired him to start Outpost.

"I'm a huge believer in the idea of millions of people living and working in space one day, and we, frankly, aren't going to have that happen if if we don't chart a better path," Dunn said.

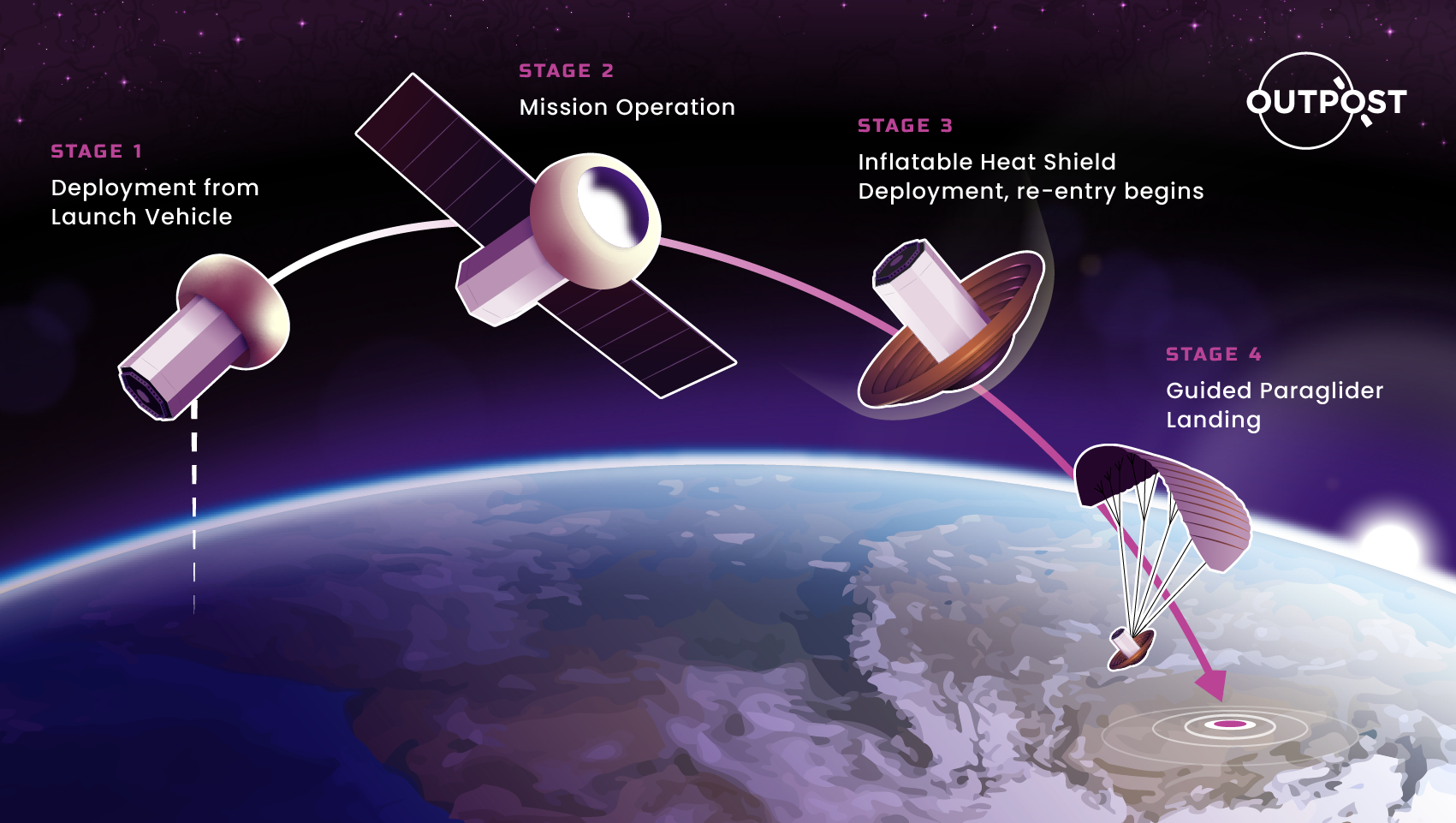

The plan is to fetch the satellites in orbit with a small vehicle and then to guide them through the atmosphere via a paraglider, at subsonic speeds; this would allow for an intact landing on Earth without the hardware burning up in the atmosphere. To bolster the business case (and profit), Outpost would fly up satellites during launch for deployment, then pick up older satellites in the same orbit to return to Earth.

"We robotically guide the paraglider and the satellite to a landing site, and in precision landing flight tests that we've done, we've been within 5 meters [16 feet] of our target," Dunn said. By comparison, NASA's successful test of a "flying saucer" inflatable Mars heat shield high in Earth's atmosphere in November came down within 10 miles (16 kilometers) of its landing target.

So far Outpost's ideas are in early designs and tests, but the company is growing quickly to meet forecast demand. Now standing at 14 employees from just two a year ago, Outpost raised $7 million in seed funding last summer on the strength of their reusable satellite ventures. And as new space stations likely replace the ISS in the 2030s, Dunn says, Outpost probably can contribute to their cargo needs as well.

Elizabeth Howell is the co-author of "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022; with Canadian astronaut Dave Williams), a book about space medicine. Follow her on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.