Juno solves mystery of what drives Jupiter's polar cyclones

Giant cyclones around Jupiter's poles are sustained by the same processes that drive the creation of ocean vortices on Earth.

Giant cyclones around the poles of the solar system's largest planet are generated by the same forces that move water in Earth's oceans, a new study has found.

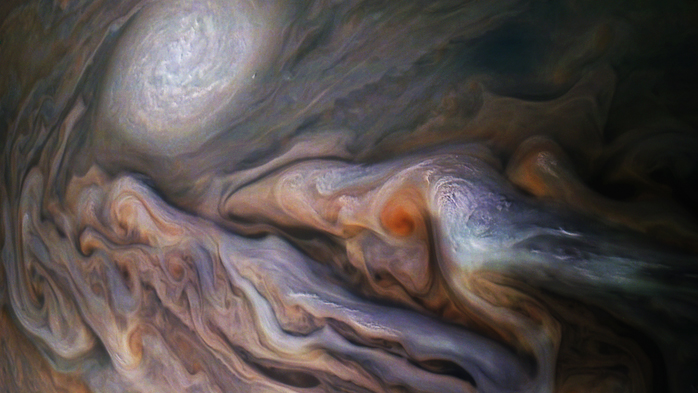

Jupiter's gargantuan polar cyclones, which are up to 620 miles (1,000 kilometers) across, were first spotted in 2016 by NASA's probe Juno. Since then, scientists have speculated that these storms are driven by convection, the process known from Earth in which hotter air expands and rises to higher, colder and denser altitudes. Until now, however, they couldn't prove the existence of this process on Jupiter.

Oceanographer Lia Siegelman, a postdoctoral researcher at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego, realized that those polar cyclones looked strikingly similar to ocean vortices that scientists study on our planet.

In photos: Juno's amazing views of Jupiter

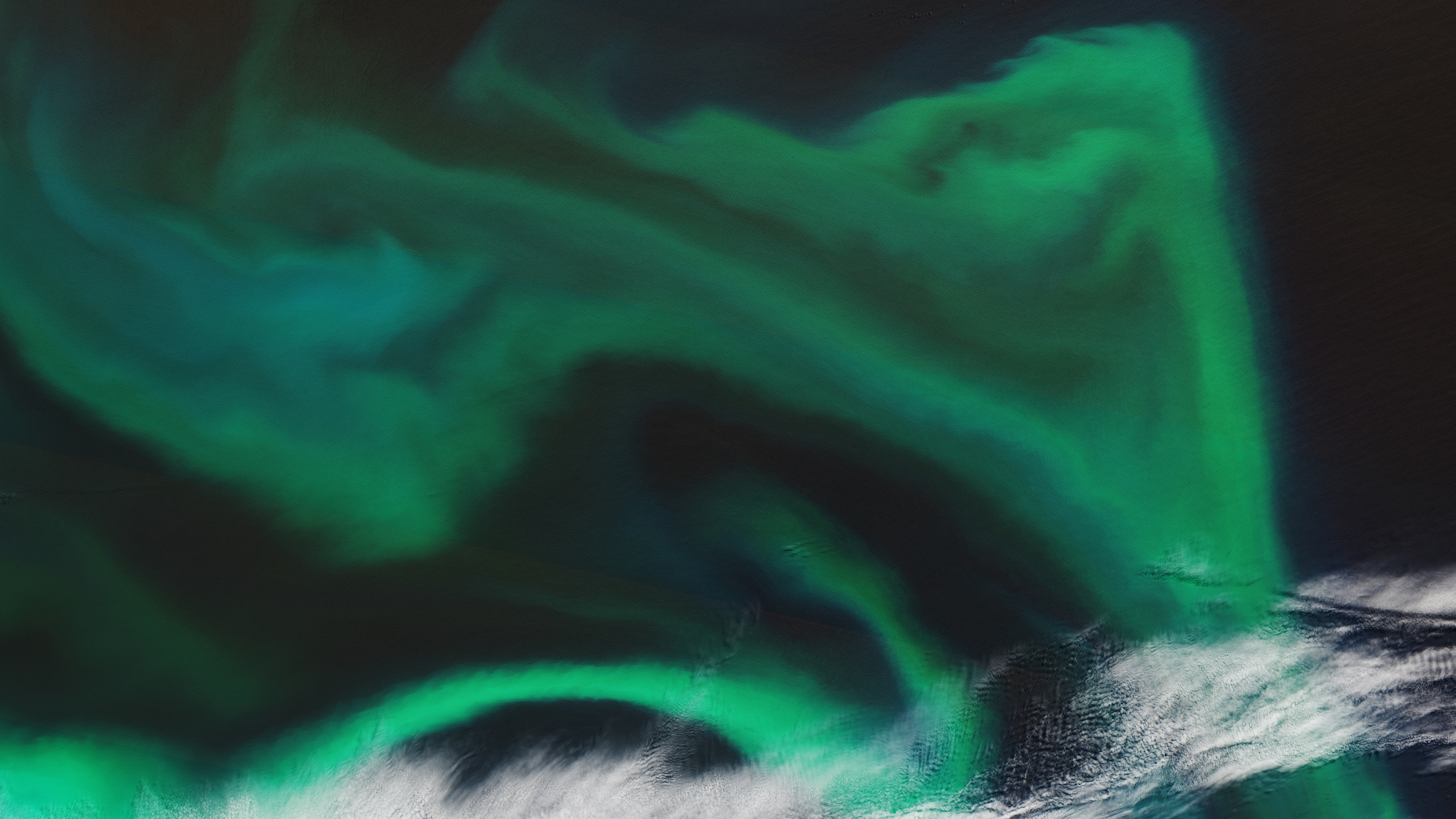

"When I saw the richness of the turbulence around the Jovian cyclones with all the filaments and smaller eddies, it reminded me of the turbulence you see in the ocean around eddies," Siegelman said in a statement. "These are especially evident on high-resolution satellite images of plankton blooms, for example."

Siegelman and her colleagues analyzed a series of images of the cyclones surrounding Jupiter's north pole captured in the infrared wavelengths, those that reveal the heat emitted by an object. The researchers used the same methodology that helps scientists study large-scale flows of air and water in Earth's atmosphere and oceans.

The analysis enabled the team to calculate the direction and speed of local winds and to track the movement of clouds. The researchers were able to distinguish areas with thin cloud cover, where they could see deeper into Jupiter's atmosphere, and those obscured by a thick blanket of fog.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The analysis proved that rising hot air transports energy within the atmosphere and feeds the clouds as they grow into large-scale cyclones, such as those observed around the poles.

"To be able to study a planet that is so far away and find physics that apply there is fascinating," said Siegelman.

She added that just as the science of Earth's oceans is now helping to unlock the mysteries of Jupiter's atmosphere, the new findings could in turn help shed new light on those large-scale processes on Earth.

For example, the physical mechanism at play on Jupiter could reveal routes of energy exchange that could also exist on our planet that scientists have not yet identified.

Juno is the first spacecraft to photograph Jupiter's poles, as previous probes, like the 1990s Galileo mission, explored the giant planet by orbiting along its equator. The Juno spacecraft found eight cyclones around the planet's north pole and five in the south, all of which are still present more than five years after their discovery.

The study was published on Monday (Jan. 10) in the journal Nature Physics.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.