What if Apollo 13 failed to return to Earth? A look back 50 years later

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

NASA bills its Apollo 13 moon mission as a "successful failure," a tale of survival and victory over an explosion in space that imperiled three astronauts near the moon. But what if NASA had failed?

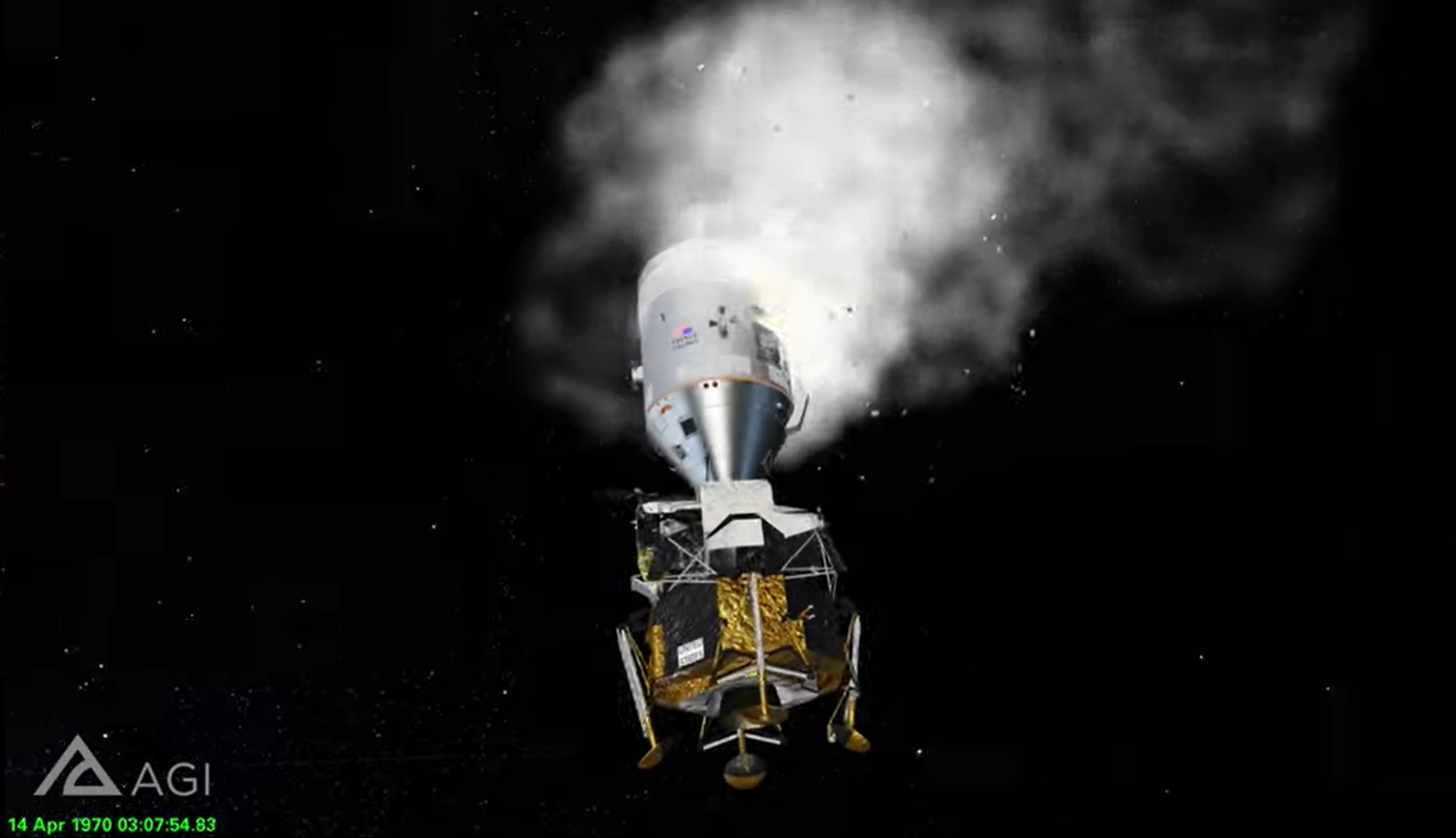

Fifty years after the iconic NASA moonshot, the software company Analytical Graphics Inc. (AGI) is taking a fresh look at that question in a video simulation that shows how the damaged Apollo 13 spacecraft would have eventually meandered back to Earth on its own — even without the astronauts helping it along, though they would have run out of air.

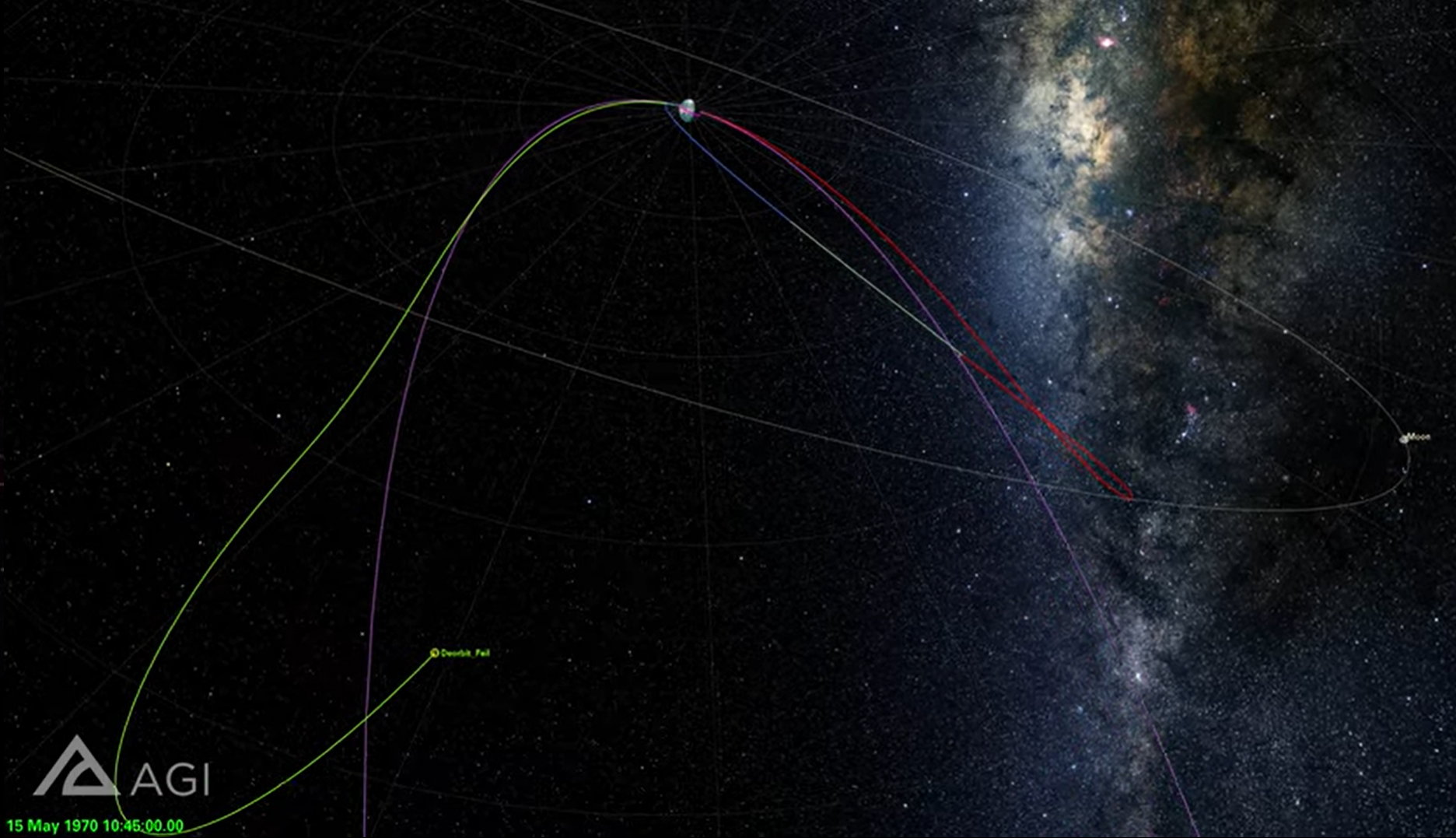

AGI unveiled a version of the video simulation in 2010 for the 40th anniversary and released it on YouTube Monday (April 13) on the 50th anniversary of the explosion that crippled Apollo 13's Odyssey command module. According to AGI's math, the Odyssey spacecraft would have reentered the Earth's atmosphere on May 20, 1970 — about five weeks after the explosion that damaged vital oxygen and power connections for Odyssey.

AGI will discuss the simulation in a free webinar, called "Revisiting Apollo 13", today (April 15) at 2 p.m. EDT (1800 GMT). You can register for it here.

Apollo 13 at 50: NASA 'successful failure' at the moon explained

Timeline: The hectic days of NASA's Apollo 13 day-by-day

While the three astronauts inside would have run out of oxygen weeks before a May return to Earth, history tells us a much happier story. In reality, astronauts Jim Lovell, Fred Haise and Jack Swigert did return home safely through a complicated rescue effort by the crew, Mission Control and teams around the world.

That hard work paid off with the crew splashing down safely on April 17, 1970 — 50 years ago this week. Two of the three astronauts (Lovell and Haise) are still alive today. Sadly, Swigert died in 1982 due to complications from cancer in 1982.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The "what if" of Apollo 13

But it's the alternate reality — what would have happened if the astronauts could not fire the engines as planned to make it back to Earth — that continues to spawn a myth, as explained by space journalist Andrew Chaikin, who wrote an account of the Apollo missions called "A Man On The Moon" and narrates the video.

"They would have missed the Earth and died a lonely death in space when their oxygen ran out," Chaikin said in the narration, with initial editions including the erroneous information. "Even more chilling," he added, "their bodies would never have returned, because Apollo 13 would have circled in space forever. Or so I always thought."

According to Chaikin, he asked AGI in 2000 to showcase key moments of the flight, not expecting anything new would come out of it. The company is an experienced hand in software development for space and other applications. In more recent decades, AGI participated in missions such as the long-running Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, the still-active New Horizons mission that zoomed by Pluto in 2015, and the MESSENGER (Mercury Surface, Space Environment, Geochemistry and Ranging) spacecraft that successfully concluded the first Mercury orbital mission in 2015.

The team was eager to take on modeling the Apollo 13 mission due to the interesting orbital profile it presented.

Related: Apollo 13's Jim Lovell and Fred Haise on their mission 50 years later

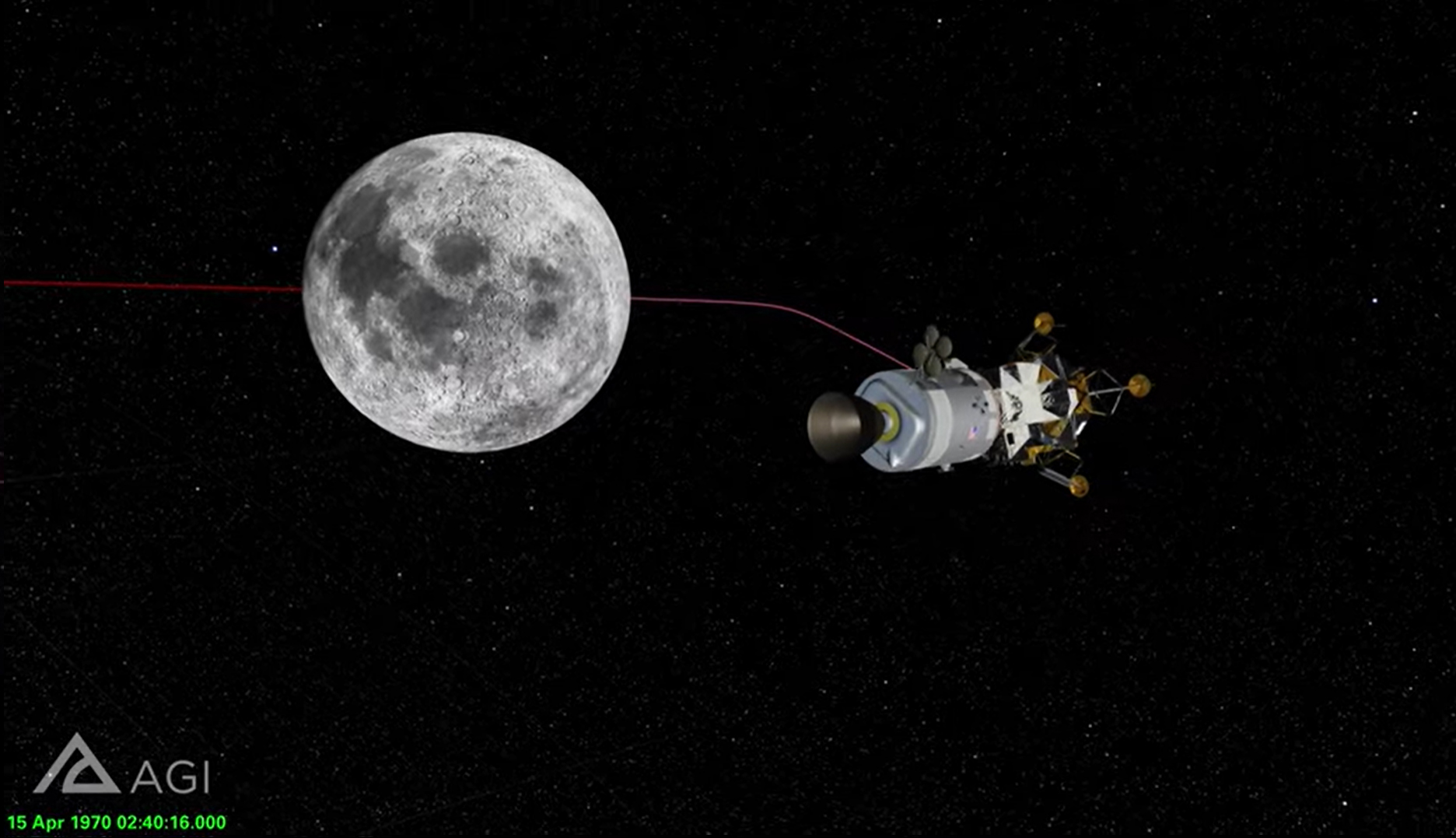

After the explosion, the Apollo 13 astronauts were initially on a path that would not automatically take their spacecraft back to Earth. However, they used their Aquarius lunar module (which Lovell and Haise intended to land on the moon) to make several engine burns to achieve a "free return trajectory." This new path brought the astronauts around the moon and back to Earth safely, instead of missing the planet altogether.

"To be fair, we didn't set out to check if they would have been a permanent monument [in space] or not," Bob Hall, a technical director at AGI, told Space.com. So it came as a shock to the team when they found the spacecraft would not circle in space forever if the path was unaltered — contradicting everything the experts said in the literature.

"We spent several days, if not a week or two, spinning our wheels. We were wondering, 'What are we modeling wrong?'" Hall said. AGI and its partner, Space Exploration Engineering, had numerous discussions internally, then eventually called Chaikin to talk things over.

A new view on Apollo 13

Help then came from an unexpected direction.

Chaikin's interviews for his book allowed him to put the team in contact with Chuck Dietrich, one of the "Retro" officers in Mission Control responsible for planning and executing Apollo 13's engine firings in space. In 1970, there was only limited computing abilities available — even at NASA — meaning that Dietrich had to work with numbers rather than simulations.

"I was a little boy during Apollo and didn't have access to that kind of stuff. The guys doing the missions [for NASA] didn't have access to it either," SEE co-founder Mike Loucks told Space.com, speaking of the simulation software he and AGI worked upon.

Luckily, Dietrich still had his old notes from April 1970, during Apollo 13's troubled days in space. It took some more conversations and calculations to verify everything, but eventually Dietrich had happy news for the team — his numbers matched theirs.

While the literature suggested an unaltered Apollo 13 trajectory would initially miss Earth by 40,000 miles (64,000 kilometers), the calculations Dietrich and the software team performed showed the spacecraft would zoom by at just 2,500 miles (4,000 km) — a low orbit that is only 10 times the altitude of the current-day International Space Station. Over time, the moon's gravity would funnel the spacecraft back to Earth.

Chaikin, who expressed surprise in the narration about the result, said Apollo 13 still stands as a testament to ingenuity. "It is a reminder to all of us of what people can accomplish when they work together and refuse to fail. I still think it's a story that will be as exciting 100 years from now as it is today, and now it's even more interesting than it was before," he said.

Both AGI and SEE further suggest the Apollo 13 trajectory work could be useful for NASA, and to commercial companies, seeking to go back to the moon in the 2020s under the agency's new Artemis program. NASA's current policy calls for landing astronauts on the moon by 2024, helped by a fleet of commercial spacecraft.

You can watch AGI's "Revisiting Apollo 13" webinar today (April 15) at 2 p.m. EDT (1800 GMT). Register here.

- This vintage NASA Apollo 13 documentary takes you back to the iconic moon mission

- Failure was not an option: NASA's Apollo 13 mission of survival in pictures

- 50 years after Apollo 13, we can now see the moon as the astronauts did

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.