Litterbugs of the Universe Busted

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Dustlittered the early universe and seeded the formation of rocky planets such asthe Earth. But where, exactly, most of the celestial grit came from wasuncertain until now.

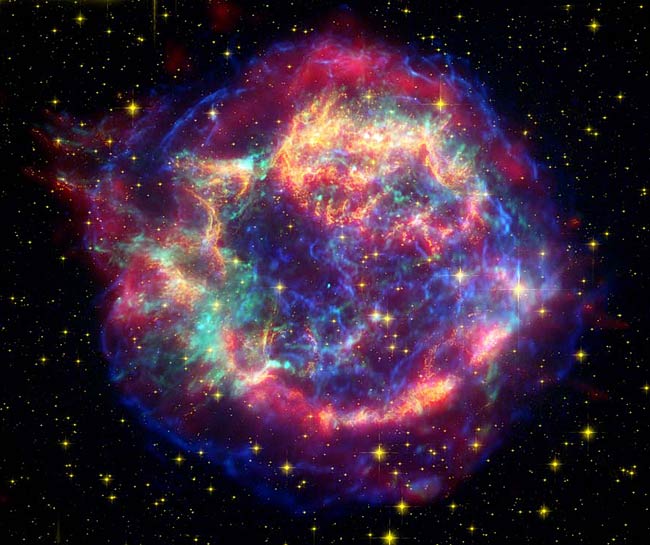

Astronomershave found 10,000 Earth masses worth of dust surrounding Cassiopeia A, theremnants of a supernova about 11,000 light-years away from our planet. The NASASpitzer Space Telescope observations show silicates, carbon, iron oxide,aluminum oxide and other dust-forming chemicals around the blown-out star.

JeongheeRho, an astronomer at the Caltech in Pasadena, Calif., thinks the discoverysignals the first strong evidence that massiveexploding stars really are the litterbugs of the universe.

"Nowwe can say unambiguously that dust — and lots of it — was formed in the ejectaof the Cassiopeia A explosion," Rho said. She and her team will detailtheir findings in the Jan. 20 issue of the Astrophysical Journal.

Stars likethe sun are thought to burn too long to seed the cosmos with enough grit, andmassive stars are probablytoo gassy and short-lived, the thinking goes. Cassiopeia A's explosion isextremely recent — the light reached Earth just 325 years ago — but Rho and herteam think cosmic dust balls similar to the remnant began producing the stuffof terrestrial planets billions of years ago.

WithinCassiopeia A, the astronomers found cool yet freshly-made dust mixed in withjettisons of gas called "unshocked ejecta" deep inside the supernovaleftovers.

"Dustforms a few to several hundred days after these energetic explosions, when thetemperature of gas in the ejecta cools down," said team member TakashiKozasa, an astronomer at Hokkaido University in Japan.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This activityhad never been seen before and hints that supernovae can crank out plenty ofdust to lead to planet formation, though it doesn't account for all of theuniverse's grit.

"Perhapsat least some of the unexplained portion is much colder dust, which could beobserved with upcoming telescopes, such as Herschel," said team member HaleyGomez, an astronomer at the University of Wales in the UK.

Set tolaunch in 2008, scientists hope to use the European Space Agency's Herschel spacecraftto find such cold dustnear quasars, thought to be hyperactive black holes, which X-rayobservations suggest could produce the stuff.

- Video: Supernova: Creator/Destroyer

- Top 10 Star Mysteries

- Gallery: Spitzer Photo Album

Dave Mosher is currently a public relations executive at AST SpaceMobile, which aims to bring mobile broadband internet access to the half of humanity that currently lacks it. Before joining AST SpaceMobile, he was a senior correspondent at Insider and the online director at Popular Science. He has written for several news outlets in addition to Live Science and Space.com, including: Wired.com, National Geographic News, Scientific American, Simons Foundation and Discover Magazine.