15 Space Travel Tips from an Astronaut

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Different astronauts will be needed for different destinations.

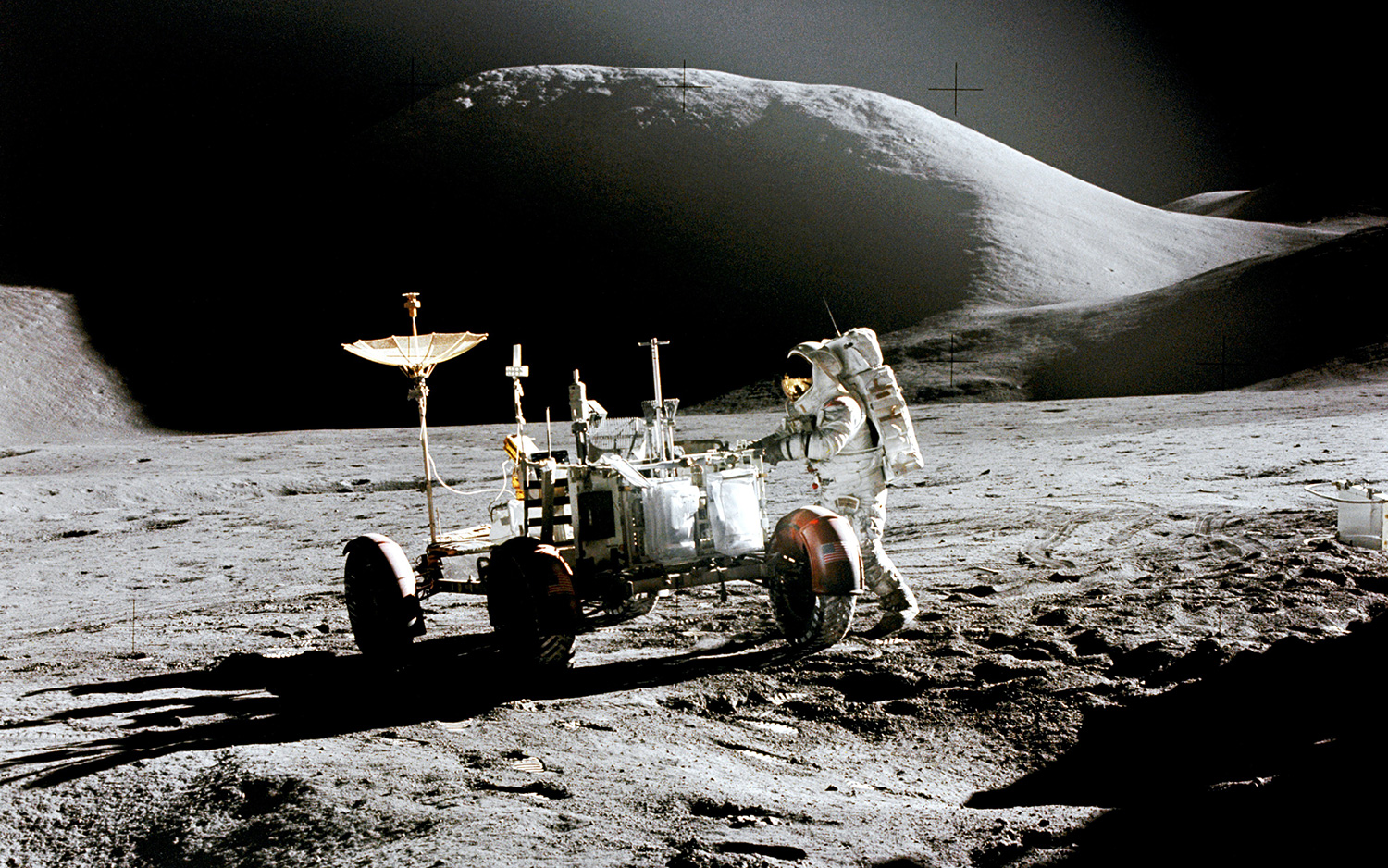

The skills required for the ISS space program are different from those needed in the days of exploring the moon. For example, astronauts today need to learn how to live in space for six months at a time or longer. During the Apollo moon missions of the 1960s and 1970s, skills such as geology or navigating rovers were more in demand. And the necessary skills will evolve as NASA stretches for new astronaut programs, Hadfield said.

For example, Hadfield said, a Mars mission would require people familiar with construction so that they could set up complex equipment on-site, far away from helping hands. There also would be a high demand for astronauts with compatible psychologies — people who could peacefully co-exist with others for years when Earth is nothing more than a shiny dot in the sky. [How Living on Mars Could Challenge Colonists (Infographic)]

In this photo: Apollo 15 astronaut Jim Irwin works in the Hadley-Apennine region of the moon during his mission in 1971.

There's a secret to the International Space Station's research success.

Astronaut crews typically perform about 200 experiments during a six-month mission on the space station, and some of these experiments are very sensitive to motion. So it is best if the space station fires its thrusters as little as possible while the experiments are underway.

To do this, Hadfield said, the space station usually flies in an orientation called local vertical, local horizontal, in which it flies much like an airplane. The "nose" or X-axis of the space station is pointed in the direction of motion, and the "bottom" (Z-axis) of the space station is pointed at Earth. This orientation means that the space station can coast, sometimes for hours, without needing to fire the thrusters and disturb any experiments on board.

In this photo: The International Space Station backdropped by Earth.

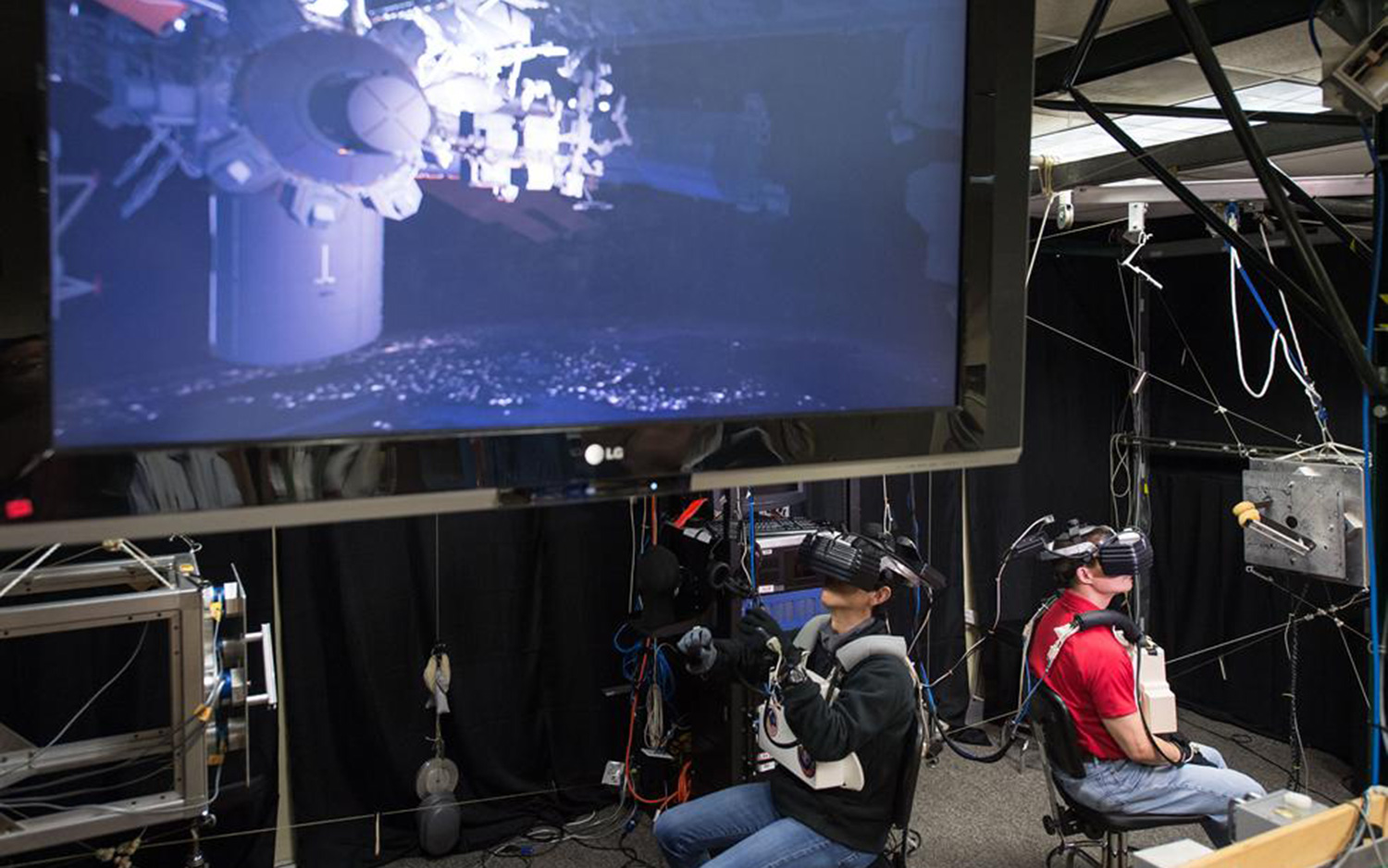

Astronauts should use a holodeck to stay entertained on long voyages.

While understanding astronaut psychology is essential to maintaining the crew's health, Hadfield said crews can also get a helping hand from technology. The holodeck of "Star Trek" would be a good technology to pursue, for example. In the science-fiction series, crewmembers use the holodeck as a way to enter the plots of detective novels, to practice skills such as fighting or even to simulate the feeling of walking on a planet with plants and breathable air.

This could be easy to implement on an exercise machine, Hadfield suggested. Instead of pedaling an exercise bike while staring at a wall, astronauts could wear a virtual-reality headset showing a route through Central Park, for example. Most importantly, the route should be dynamic; if an astronaut chooses to turn left on the exercise bike, the view in the headset should change. It would even be better if the headset could pipe in smells and sounds from a park environment, Hadfield said.

In this photo: Expedition 44/45 astronauts Kimiya Yui and Kjell Lindgren practice in the Virtual Reality Lab at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston.

Today's space station landings are informing Mars spaceship design.

After spending six months or more in space, astronauts generally feel very sick and weak upon arriving back on Earth. They usually are carried to recovery tents just minutes after landing. There are at least a couple of reasons for that. The first is that the astronaut may be too weak to walk right away. The second is that doctors want to test how quickly astronauts recover, and that is best done in the controlled environment of a tent.

Why is it important to recover quickly? An astronaut crew arriving on Mars may have to set up equipment or go exploring right away. If they can't, Hadfield said, this means a very different kind of landing ship would be required. The design of the Martian craft would change; it would need more food, oxygen, water, power and living space so that astronauts could spend a few days or weeks recovering their strength. Therefore, the ability of crews to perform tasks will directly influence the design of future spaceships, he said.

In this photo: Expedition 38/39 NASA astronaut Rick Mastracchio is carried to a medical tent minutes after landing in Kazakhstan in May 2014.

Red Planet astronauts will use diaries like Mark Watney's video journal in "The Martian."

In the 2015 movie "The Martian," astronaut Mark Watney records regular video diaries to explain tasks that he is performing on the Red Planet. It's an important tool when communications to Earth take (on average) 20 minutes, one way. Theoretically, these videos could be sent to Mission Control as an alternative to back-and-forth conversation.

"It's sort of perfect," Hadfield said of the video diaries in "The Martian," adding that he participated in an underwater mission on the Aquarius habitat in which his crewmates would do much of the same thing. "I found my crew at the bottom of the ocean would naturally say, 'Let's not send one piece of information. Let's record a little video and go around and talk about the five problems that we're facing, and make sure that we … not just show the questions, but why we have the questions.'"

Astronauts today continue to practice communications with time delays not only in Aquarius but also on the space station. This helps astronauts and Mission Control figure out which tasks can be done autonomously and which ones might need more help from people on Earth. ['The Martian' Might Be the Most Realistic Space Movie Ever Made]

In this photo: Matt Damon as Mark Watney in the 2015 movie "The Martian."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.