NASA Agreement Sign of Stratolaunch Engine Development Program

WASHINGTON — An agreement to do engine testing at a NASA center is the latest sign that Stratolaunch is considering developing its own launch vehicle for its giant aircraft.

The Space Act Agreement between Stratolaunch and NASA’s Stennis Space Center, signed Sept. 13, covers "reimbursable testing and related support services to Stratolaunch to support propulsion, vehicle, and ground support system development and testing activities." NASA published the agreement on its website as part of a provision in a NASA authorization act signed into law this year to disclose such agreements.

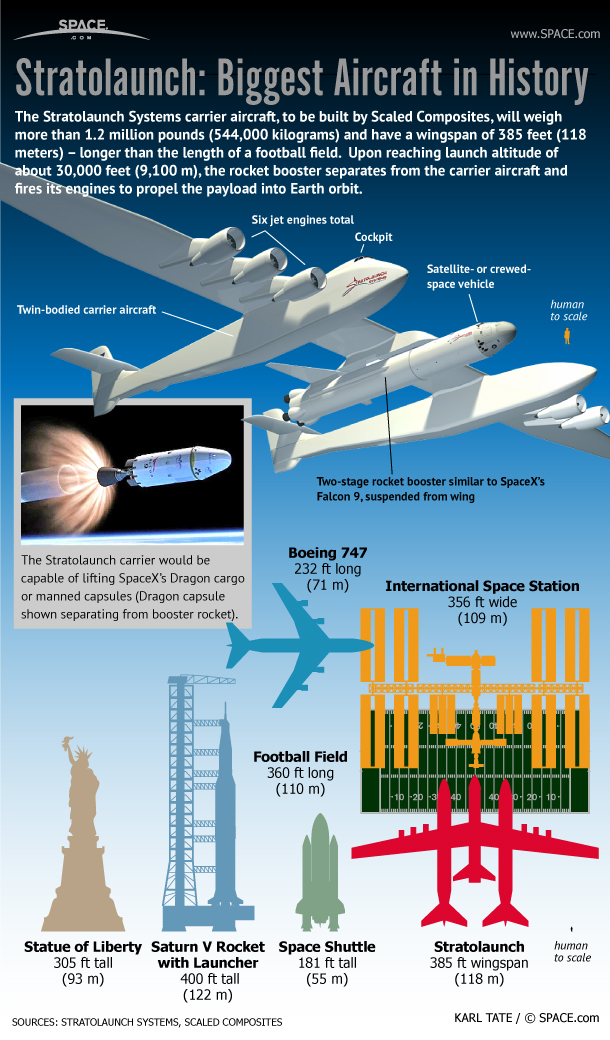

An annex to that umbrella agreement specifies that it involves "testing of its propulsion system test article element 1" at Stennis's E1 test stand. That facility has supported engine tests by a number of companies in the past under similar agreements that provide access to test stands there on a non-exclusive basis. [Stratolaunch: The World's Largest Airplane in Pictures]

In a schedule included in the annex, Stratolaunch plans to deliver the test article to Stennis for "fit tests and checkouts" by the end of May 2018, with the test series completed by the end of 2018. Stratolaunch will pay NASA $5.1 million under the reimbursable agreement to cover costs of the test campaign, including an upfront payment of $1 million.

The agreements don't provide technical details about the hardware Stratolaunch plans to test at Stennis. Steve Lombardi, a spokesman for Stratolaunch, confirmed the agreement but didn't disclose details about what the company is developing.

"I can confirm we're working at Stennis Space Center on a project that is still in an early stage," he said in an email response to a SpaceNews inquiry about the NASA agreements. "As we've said in the past, we're exploring a number of launch system possibilities to provide reliable access to space."

Recent personnel moves suggested that Stratolaunch was looking into developing its own launch vehicle that could be used with its large aircraft currently undergoing testing in California. In June, Stratolaunch hired Jeff Thornburg as vice president of propulsion "to explore new approaches to making access to space more convenient, reliable, and routine," according to a statement by Jean Floyd, the company's chief executive.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Thornburg previously worked at SpaceX, where he was the senior director of propulsion engineering and served as the lead engineer on that company's Raptor methane/liquid oxygen engine. He also worked on the J-2X upper stage engine program at NASA as a lead engineer and technical project manager.

The company's website also includes two job openings for "propulsion lead engineer" positions at its Seattle offices. "As a Propulsion Lead Engineer, you will be responsible for working directly with the VP of Propulsion to develop engine component hardware and engine systems," the job description states, including "various aspects of the design, development, fabrication, and testing for engine development."

Stratolaunch has attracted more attention for its giant aircraft, designed to serve as an airborne launch platform. That effort has seen steady progress, with the aircraft rolled out of its hangar at the Mojave Air and Space Port for the first time in May, followed a few months later by the first tests of its six jet engines.

By contrast, the launch vehicle that airplane will carry has changed several times. When the project was first announced in late 2011, SpaceX was a partner, providing a version of its Falcon 9 rocket with four to five engines, instead of nine, in its first stage.

The companies parted ways within a year, though, and Orbital Sciences (now Orbital ATK) replaced it with a vehicle called Thunderbolt that featured solid-propellant lower stages and an upper stage powered by an Aeroject Rocketdyne RL10 engine.

Stratolaunch, though, decided a few years later to discontinue that effort, seeing greater demand in small satellites that require smaller vehicles. In October 2016, Stratolaunch announced a partnership with Orbital ATK where it would use the existing Pegasus XL rocket on the plane. One concept shown by the company involves flying three Pegasus rockets at a time.

The space industry has taken a skeptical view to that plan, noting that Pegasus XL launches rarely today, and primarily for NASA, given its high costs. There have been five Pegasus XL launches in the last decade.

Stratolaunch has argued it can get lower costs by purchasing multiple Pegasus vehicles at a time. Launching three rockets on a single flight has benefits, particularly in the national security field.

"With one aircraft sortie, you could basically launch an entire architecture of satellites into multiple planes, assuming each launch carries multiple satellites," said Steve Nixon, vice president for strategic development at Stratolaunch, at a June panel discussion.

This story was provided by SpaceNews, dedicated to covering all aspects of the space industry.

Jeff Foust is a Senior Staff Writer at SpaceNews, a space industry news magazine and website, where he writes about space policy, commercial spaceflight and other aerospace industry topics. Jeff has a Ph.D. in planetary sciences from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and earned a bachelor's degree in geophysics and planetary science from the California Institute of Technology. You can see Jeff's latest projects by following him on Twitter.