NASA Space Telescopes to Peer Deeper Into Universe Than Ever Before

Three NASA space telescopes are teaming up to give astronomers their best-ever looks at some of the most distant objects in the universe.

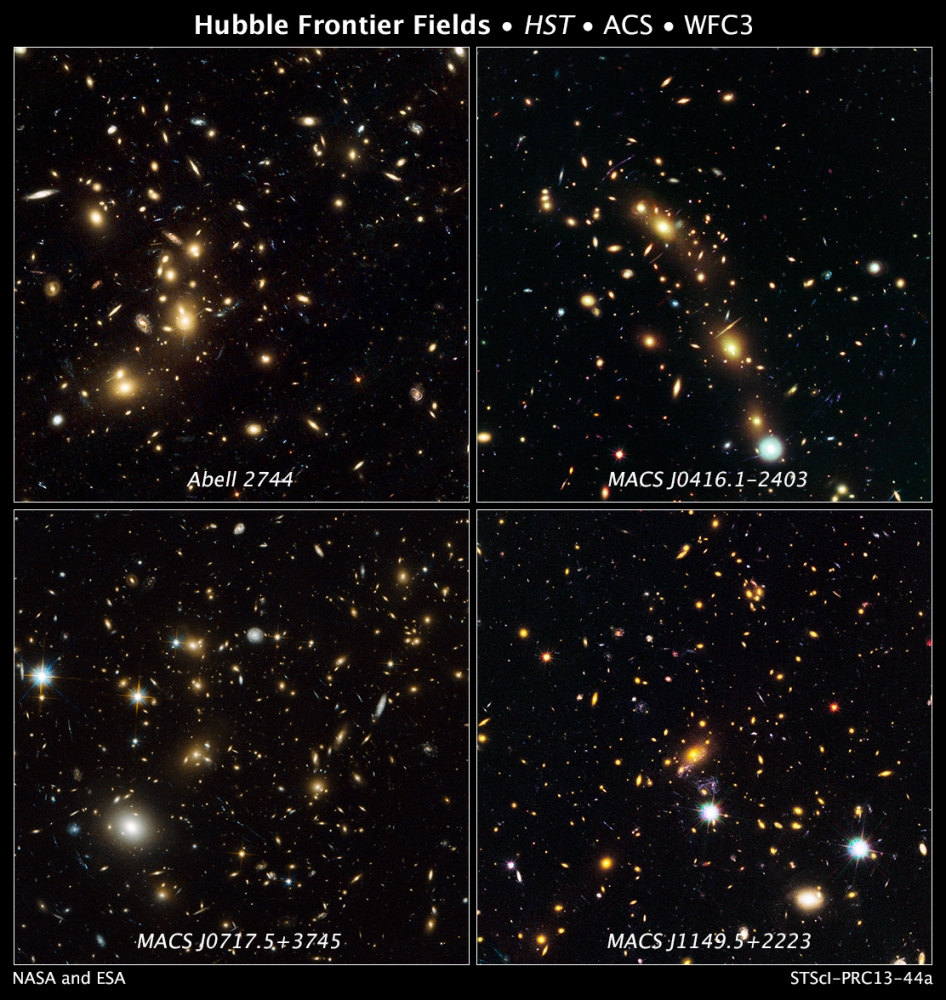

The space agency's Hubble, Spitzer and Chandra space telescopes will collectively observe six huge galaxy clusters over the next three years as part of a project called The Frontier Fields. Working together, the trio should be able to spot galaxies that existed just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang created our universe 13.8 billion years ago, NASA officials said.

"The Frontier Fields program is exactly what NASA's Great Observatories were designed to do: working together to unravel the mysteries of the universe," NASA science chief John Grunsfeld said in a statement. "Each observatory collects images using different wavelengths of light, with the result that we get a much deeper understanding of the underlying physics of these celestial objects." [Cosmic View! Latest Hubble Space Telescope Photos]

The Hubble Space Telescope observes in visible, near-infrared and near-ultraviolet wavelengths. Spitzer is optimized to view in the infrared, while Chandra sees best in X-ray light.

The Frontier Fields project will take advantage of a phenomenon called gravitational lensing, in which the gravitational field of a massive foreground object bends and brightens the light from a more distant object, acting like a lens.

In this case, the six huge galaxy clusters — starting with Abell 2744, which is also known as Pandora's Cluster — will be the lenses, and the magnified objects will be extremely dim and far-flung galaxies, some of which have likely never been observed before, researchers said.

"The idea is to use nature's natural telescopes in combination with the great observatories to look much deeper than before and find the most distant and faint galaxies we can possibly see," Jennifer Lotz, a principal investigator with the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, said in a statement.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Data from Hubble and Spitzer will help astronomers measure these galaxies' distances and masses accurately, researchers said. Chandra's observations, meanwhile, will help astronomers determine the galaxy clusters' masses and gravitational lensing power, as well as spot background galaxies harboring supermassive black holes at their cores.

"We want to understand when and how the first stars and galaxies formed in the universe, and each great observatory gives us a different piece of the puzzle," said Peter Capak, Spitzer principal investigator for the Frontier Fields program at NASA's Spitzer Science Center at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.