Best Time to See the Moon This Month Is Now

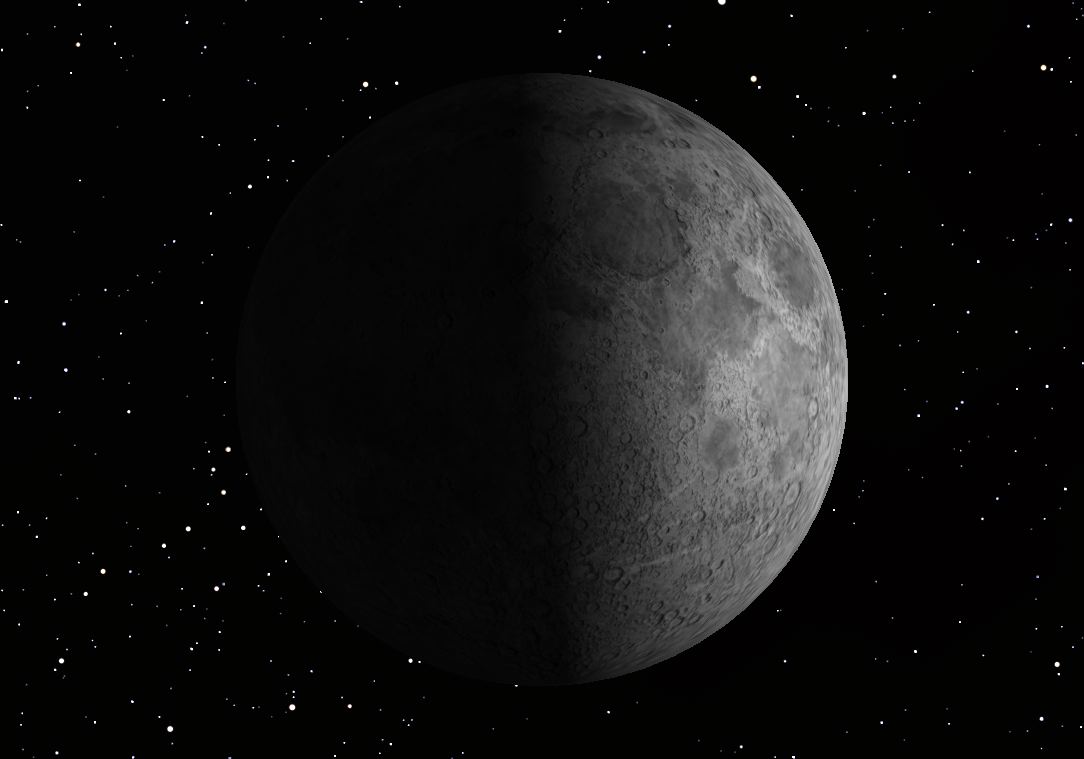

The next few nights are the best times of the month to observe the surface of the moon with telescopes, binoculars or even your naked eye. That's because the sun is rising along the center line of the moon, casting the lunar mountains and craters in high relief.

Beginners in astronomy are often surprised that the best time to study the moon is not at full moon, which will occur on next Thursday (Sept. 19). During a full moon the sun is high overhead in the center of the moon, and the surface looks like the desert at high noon.

The best time to observe the moon is when the sun is falling obliquely, casting long shadow, which is what you see during the moon's first and third quarter phases [Phases of the Moon Explained (Infographic)]

Third quarter is a bit of a problem because it occurs when the moon is in the dawn sky. First quarter, on the other hand, occurs when the moon is high in the sky at sunset, perfect for evening observing.

The moon is so close to us that you don't really need a telescope to study it. Even without any optical aid, the major features of the moon can be clearly seen, if you take the time. In fact, you can see more detail on the moon with your naked eye than you can see on any of the planets with a powerful telescope.

When you look at the first quarter moon, you are seeing a sphere lit by the sun from the right side (in the northern hemisphere; left side in the southern hemisphere). The surface of the moon varies in reflectivity, so that you see a pattern of light and dark. The lighter areas are the older mountainous regions, mostly on the southern half of the moon; the darker areas are younger lava flows, mostly in the north.

Early observers mistook these for seas and oceans, and named them accordingly. Later astronomers realized that the moon is an airless waterless body, and that its "seas" are dryer than the driest deserts on Earth. The water which has been discovered recently on the moon is buried deep beneath the surface.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

If you examine the moon more closely in binoculars or a telescope, your attention will be drawn to the "terminator," the narrow band down the middle of the moon where dark meets light. This is where the sun is rising.

Ordinary binoculars can give a surprisingly detailed view of the moon, especially if they are steadied by mounting them on a tripod. Many binoculars have a tripod socket hidden under a small cap in the hinge between their two halves, but you will need a small L-shaped adapter to connect this to a standard camera tripod. You will be amazed at the improvement a tripod mount makes to the view.

The 10x50 size binocular is the most popular among astronomers. Its 10 times magnification and 50mm objective lenses provide excellent views of both nearby objects like the moon and distant objects like star clusters and galaxies. In recent years more powerful binoculars have become widely available at amazingly low prices. The 15x70 size gives particularly good views of the moon, but must be mounted on a tripod.

Because the sun is rising over the terminator, even the slightest variation in topography is exaggerated by the rising sun. Look especially for craters and isolated mountains on the plains. With the extra magnification afforded by a small telescope, you can actually watch the sun rise over craters in real time.

With a good map of the moon in hand, such as the ones available from Sky Publishing, you can become familiar with the “geography” of the moon. More than a thousand craters bear the names of famous astronomers of the past. I especially recommend the Sky & Telescope Field Map Of The Moon, which is on the right scale for convenient use with a telescope, and is laminated to protect it from dew. There is even a mirror-reversed version of this map for use with telescopes with mirror diagonals. Both feature beautiful cartography by Antonín Rükl, the dean of lunar mapmakers.

This article was provided to SPACE.com by Starry Night Education, the leader in space science curriculum solutions. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.