The Sun May Have Grown in Fits and Starts

INDIANAPOLIS — The sun was probably an active, "feisty" star in the early days of its evolution, scientists suspect.

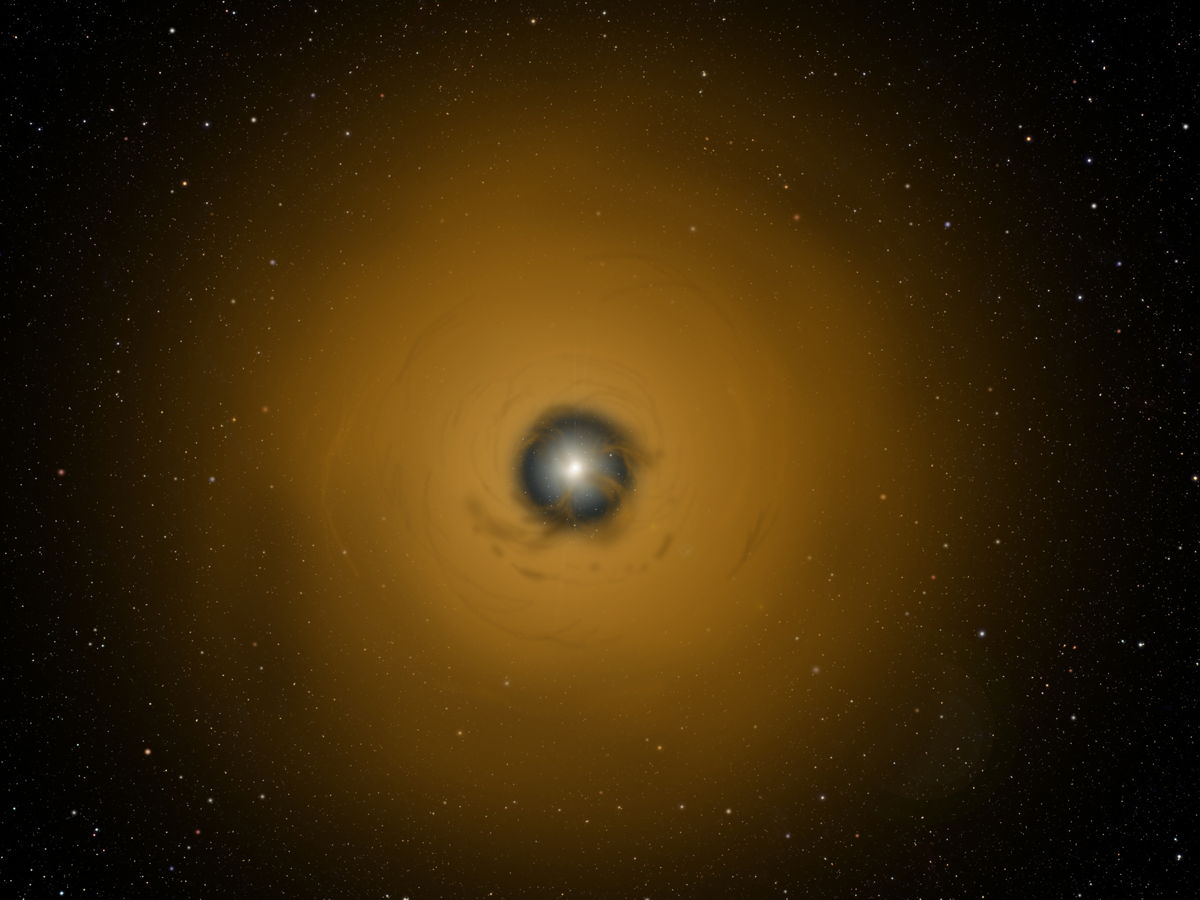

A group of researchers have been examining a young star similar in mass to the sun to understand what Earth's closest star could have looked like early in the solar system's history. The star, called TW Hydrae, shines about 190 light-years from Earth and weighs about 80 percent as much as the sun.

"By studying TW Hydrae, we can watch what happened to our sun when it was a toddler," Nancy Brickhouse of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass., said in a statement.

TW Hydrae is about 10 million years old and could be going through a process that the 4.6 billion-year-old sun undertook early in its stellar existence. The young star is still accreting gas from a disk that surrounds it. The gas is being funneled into the star along magnetic field lines.

Brickhouse and her team observed the infalling gas using NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory as well as other ground-based methods. The researchers saw the gas crash into the star, which can create a shock wave and heat the gas to more than 5 million degrees Fahrenheit (2.8 million degrees Celsius). The gas cools once it falls further into the star.

"By gathering data in multiple wavelengths we followed the gas all the way down," Brickhouse said. "We traced the whole accretion process for the first time."

Through tracking the gas on its path into the star, Brickhouse noticed that the accreting gas didn't fall into the star at an even rate. Instead, the star grew by fits and starts, changing from one day to the next.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The observations are giving researchers a window into the relationship between the star's magnetic fields and its orbiting disk of material that could clarify how magnetism affects similar processes around the galaxy, the scientists said.

Follow Miriam Kramer @mirikramer and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.