'Comet of the Century' Could Create New Meteor Shower

An incoming comet that may well turn out to be the "comet of the century" could create an unusual kind of meteor shower, scientists say.

When Comet ISON passes by the Earth this year, it is possible that the dust sloughed off by the comet's tail will create an odd meteor shower when the planet passes through the stream of tiny particles that once were a part of the comet's tail.

"Instead of burning up in a flash of light, they [the particles] will drift gently down to the Earth below," University of Western Ontario meteor scientist Paul Wiegert said in a statement. [See Photos of Comet ISON]

The specks of dust will be travelling at a speed of 125,000 mph (201,168 km/h), but once they hit the Earth's atmosphere, they will slow to a halt, according to Wiegert's computer models.

Because of this, observers on the ground probably won't be able to see the meteors as they fall through the atmosphere in January 2014, Wiegert added.

"Don't expect to notice," NASA officials said of the shower in a press release. "The invisible rain of comet dust, if it occurs, would be very slow. It can take months or even years for fine dust to settle out of the high atmosphere."

All hope for a brilliant show might not be lost, however. The dust from ISON could create "noctilucent clouds" — icy night-shining clouds above the Earth's poles that glow blue.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Electric-blue ripples over Earth's polar regions might be the only visible sign that a shower is underway," NASA officials said.

ISON is on a course through the solar system, on its way toward the sun. At its closest pass, the comet will be within 730,000 miles (nearly 1.2 million kilometers) of the solar surface on Nov. 28.

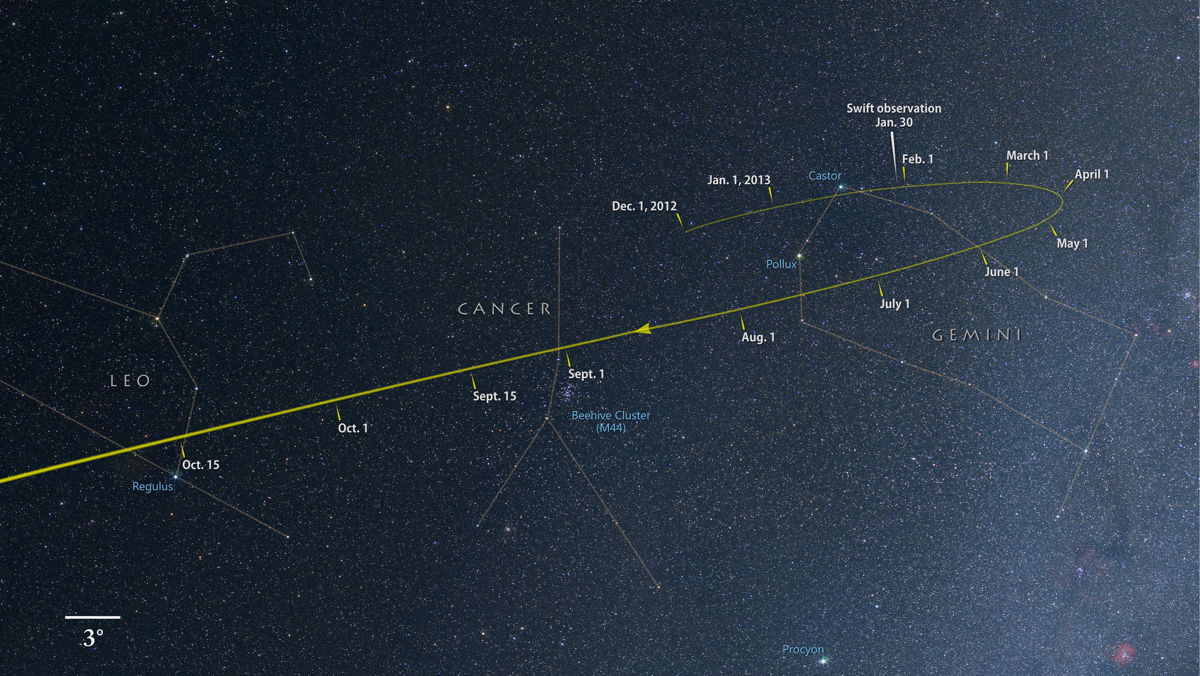

NASA's Swift spacecraft caught sight of the speeding comet in January when the ball of ice and dirt was discharging more than 112,000 pounds (50,802 kilograms) of dust every minute as it passed Jupiter. Wiegert made his calculations by using that data to understand where the dust might end up on Earth's orbit.

It's possible that the comet will fizzle out before becoming visible from the Earth, burning up in the intense heat of the sun, or the heat from the star could make the comet shine even more brightly.

Predicting the comet's behavior is particularly difficult because astronomers believe that this is the first time ISON has made it into the inner solar system from the Oort cloud — a distant mass of icy bodies that encircles the solar system.

NASA is in the midst of a Comet ISON Observing Campaign. The space agency's initiative coordinates observatories in space and on the ground to track the comet as it makes its way toward the Earth. The Hubble Space Telescope and Swift are both part of this effort.

ISON's official name is C/2012 S1 (ISON) and was discovered in September 2012 by amateur astronomers Artyom Novichonok and Vitali Nevski.

Follow Miriam Kramer on Twitter and Google+. Follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.