Enterprise: The Test Shuttle

The first space shuttle, Enterprise, never made it to space. In fact, Enterprise was not capable of spaceflight; it was built without engines or a heat shield. Nevertheless, it made major contributions to the space shuttle program as a test vehicle and it also helped popularize the program.

Enterprise also served as a source for parts after the Columbia space shuttle disaster in 2003. (Enterprise's parts were used to test out a theory that falling foam had damaged Columbia's wing during launch.) Enterprise also survived Hurricane Sandy in 2012 shortly after the shuttle was moved to New York City's Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum. While the shuttle and its pavilion were damaged in the storm, the display re-opened in 2013 after a new pavilion was constructed.

Enterprise was the culmination of decades of research in "lifting bodies." Between 1963 and 1975, the Air Force and NASA researched methods of flying winged vehicles back from space and landing them like an aircraft. Six different prototypes were manufactured and flown in 223 glide tests, providing a set of information that was used for the shuttle and similar concepts developed by NASA.

Enterprise at a glance

- First taxi test: Feb. 15, 1977

- First captive-inert flight: Feb. 18, 1977

- First captive-active flight: June 18, 1977

- First free flight: Aug. 12, 1977

- Last free flight: Oct. 26, 1977

- Time in space: None (test orbiter)

- Notable: Enterprise was a test space shuttle not intended for flights in space. It was used for test flights, public relations goodwill tours, and as a source for parts during the investigation into the Columbia space shuttle disaster that took place in 2003.

Star power

The spacecraft was originally designated Constitution. NASA planned to roll out the shuttle on Sept. 17, 1976, which was Constitution Day. But fans of the television show "Star Trek" saw things a little differently. As the shuttle was being developed, fans of the science fiction series organized a campaign and sent letters to the White House asking for the name Enterprise.

It is said that then-president Gerald Ford got tens of thousands of these letters. Recognizing the chance to cash in on popular sentiment, the name was changed to Enterprise.

When Enterprise was brought out of its manufacturing facility in Palmdale, Calif., NASA naturally held an event to celebrate it. Most of the original cast from Star Trek attended the unveiling, posed for pictures in front of the shuttle, and lent a little star power to the space program.

Flying deadstick

Enterprise was used in five "drop tests" in California, allowing NASA astronauts to get a feel for how the shuttle would fly during the descent back to Earth.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The space shuttle was designed to land on Earth as a deadstick; it would not be powered; the pilots would guide it to the surface using turns and computer guidance. Getting the landing exactly right, on the first time, would be crucial; there was no easy way to turn around and make a second attempt.

Enterprise would fly several glide tests, leaving the back of an aircraft and flying unpowered to the ground.

Preparing to take flight

NASA tested the shuttle several times on the ground before setting it aloft. First, in February 1977, the agency did some taxi tests with Enterprise perched above a modified 747 passenger aircraft. The aircraft type (known as the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, or SCA) would later be used to carry the shuttles between California and Florida if the shuttle landed at Edwards Air Force Base.

Next, NASA flew the SCA five times with the shuttle on top of it. There was no crew inside the shuttle, as these were tests to determine how the aerodynamics on the aircraft would change with a 100-ton spacecraft perched on its back.

Following that were three flights with crew inside. Still, the shuttle did not leave the safety of the aircraft as everyone was focused on making sure the systems operations and the crews knew the procedures for the landing.

On the wing

Enterprise was finally released into the air on Aug. 12, 1977. Fred Haise, best known as a crewmember on Apollo 13, commanded the flight with Gordon Fullerton as second-in-command. Fullerton would go on to fly in shuttle missions twice.

The SCA released Enterprise at about 24,000 feet and quickly banked away as the shuttle took to the air for the first time. After just five minutes and 21 seconds in the air, Enterprise delicately touched down on the dry lake bed around Edwards Air Force Base.

For subsequent flights, Haise and Fullerton took turns with the other approach and landing crew, who were Joe Engle and Richard Truly. The crews flew the shuttle five times in 1977. For the first three flights, Enterprise wore a tail cone to minimize drag. That cone was removed for the last two flights to better simulate how the shuttle would behave during an actual landing.

NASA thought so highly of the skills of Engle and Truly that both flew the two-person second shuttle flight in space — even though both of them were rookie astronauts.

Tests and tours

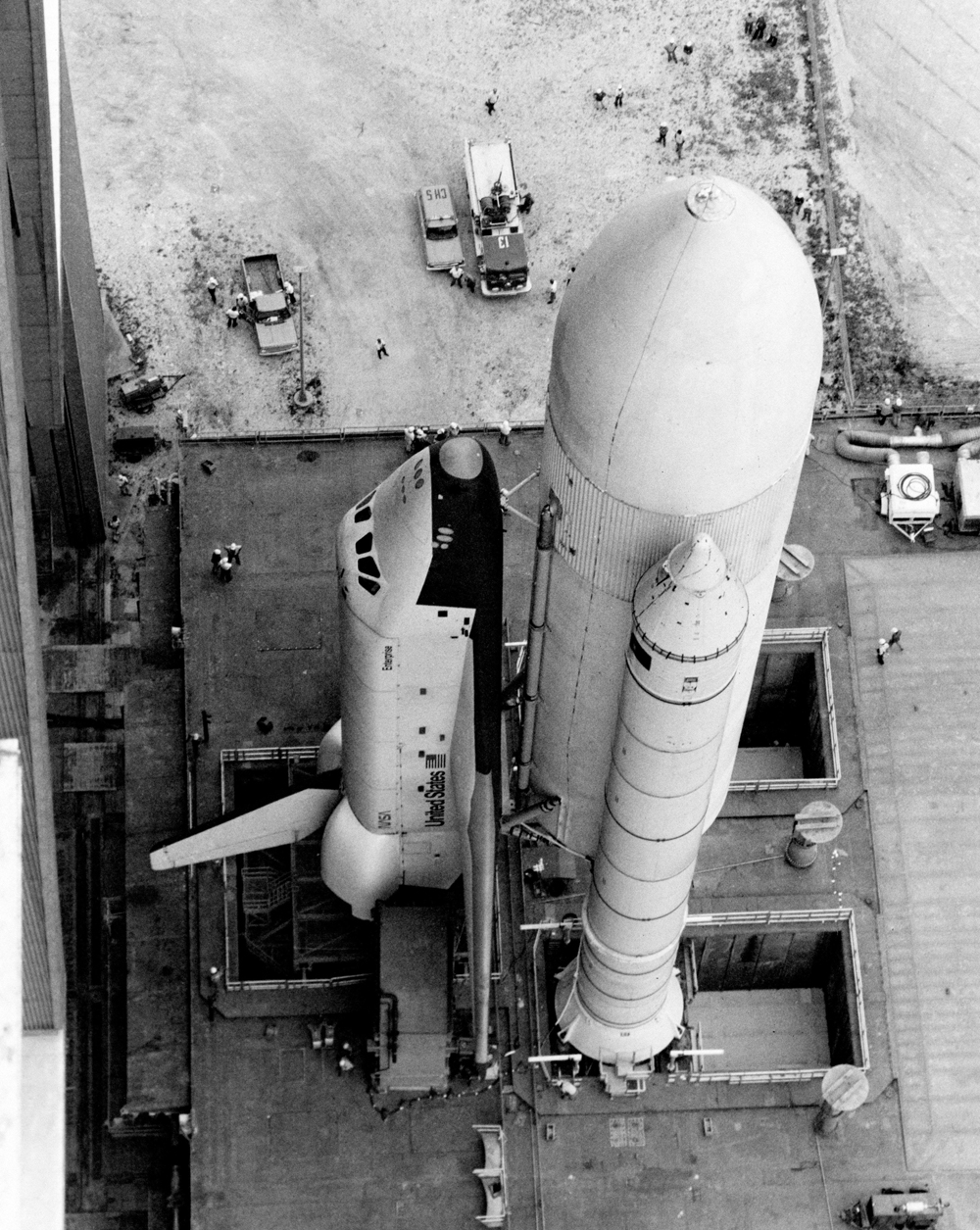

The approach and landing tests were just one facet of the space shuttle program that needed to be examined, so after Enterprise's flights concluded, the shuttle went through more tests. The shuttle was fitted for future ferry flights, and measures were taken to reduce aerodynamic drag. Ground vibration tests were performed as Enterprise sat atop the SCA. Enterprise also was attached to an external tank and solid rocket boosters to test the launch configuration.

The shuttle era began when Columbia, the first shuttle to go into space, launched on April 12, 1981. Nearly two years later, on April 4, 1983, another shuttle, Challenger, was added to the fleet. With the space shuttle program well under way, Enterprise took on a new role as an ambassador for the program.

In 1983, Enterprise went on a world tour that included Canada and several European countries (England, France, Germany and Italy), most notably visiting an air show in Paris. The next year, the SCA brought Enterprise from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California to Alabama, to be ferried by barge to the 1984 World's Fair in New Orleans.

Retirement

After nearly a decade serving NASA's purposes for testing and public relations, Enterprise left its latest stop at the Dryden Flight Research Facility for transport to the Kennedy Space Center in September 1985. On Nov. 18, 1985, it flew to Dulles Airport in Washington, D.C., to become the property of the Smithsonian Institution.

However, the Smithsonian had no public place to display Enterprise, so it remained in storage in a hanger for nearly two decades.

In the early 2000s, the Smithsonian completed the major fundraising for a $130 million goal to build the Udvar-Hazy Center, an airport annex to the Smithsonian. It was named after the center's major donor, Steven F. Udvar-Hazy.

Enterprise was the centerpiece of the space wing of the facility when it opened to the public in December 2003. At the time, Enterprise's leading edge panel was removed for testing in the wake of the shuttle Columbia's destruction earlier that year.

Researchers at the Southwest Research Institute fired external fuel tank foam insulation at nearly 530 mph at the panel. It was intended to simulate the foam strike that fatally wounded Columbia during launch.

Enterprise remained at the museum until April 2012, when it was flown to New York City for display at the Intrepid Sea, Air and Space Museum on the Hudson River. Udvar-Hazy would receive the space shuttle Discovery after the program's retirement.

Enterprise's right wing was slightly damaged during transport on the water to the museum, as a wave pushed the shuttle (which was riding on a barge) into a railroad bridge abutment. The damage was repaired before Enterprise's display opened to the public July 19, 2012. Later that year, Hurricane Sandy hit New York City and caused damage across the city, including to Enterprise and its pavilion (which collapsed during the storm). Enterprise's display temporarily closed until 2013, after a new pavilion was opened to the public.

Today, Enterprise remains on display at the Intrepid. It serves as a reminder of how important test flights are to developing a success space program, as well as a testament to how hard NASA worked in the early days to understand how a space shuttle behaved during landing.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.