Twin Moon Probes Crash into Lunar Mountain

A pair of twin gravity-mapping moon probes ended their science mission today (Dec. 17) by becoming intimately familiar with the pull of the natural satellite.

The washer-and-dryer-size Grail spacecraft slammed into a crater rim near the moon's north pole at 5:28 p.m. EST (2228 GMT) Monday. The pair was crashed intentionally because their low orbit and remaining fuel levels precluded further scientific operations.

The impacts, which were directed by earlier rocket burns, were designed to keep the two probes from colliding with historic sites on the surface of the moon.

"NASA wanted to rule out any possibility of our twins hitting the surface anywhere near any of the historic lunar exploration sites like the Apollo landing sites or where the Russian Luna probes touched down," said David Lehman, Grail project manager at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. [Video: Grail Probes Crash Into Moon]

Before each of the spacecraft's rocket firings, which were performed on Friday (Dec. 14), navigators calculated the odds of either probe impacting at an historic site at about seven in one million.

Instead, the Grail spacecraft, which were named "Ebb" and "Flow" by contest-winning elementary school students in Bozeman, Mont., came down hard in the vicinity of the Goldschmidt crater located on the near side of the moon. Each spacecraft hit the lunar surface at roughly 3,760 mph (6,050 kph), researchers said.

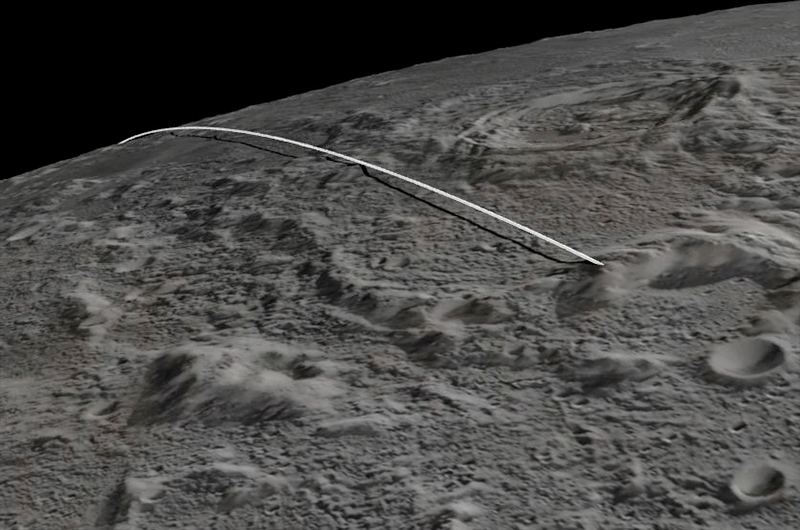

The collisions were separated by about 32 seconds, with Ebb leading Flow into the side of a mountain at a site that has now been named after the late Sally Ride, America's first woman in space. There was no imagery of their end because the area was in shadow at the time

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Mapping their own demise

The $496 million Grail mission (short for Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory) launched on board a Delta 2 rocket from Cape Canaveral, Fla. in September 2011. Ebb and Flow arrived at the moon on New Year's Day.

In orbit, the duo's successful prime and extended science missions produced the highest-resolution gravity field map of any celestial body, providing a better understanding of how the Earth and other rocky planets in the solar system formed and evolved.

The map was created by the spacecraft transmitting radio signals to define precisely the distance between them as they flew around the moon in formation. As they orbited over areas of greater and lesser gravity caused by visible features — such as mountains and craters — and masses hidden beneath the surface, the distance between the two spacecraft changed slightly.

"What this [lunar] map tells us is that, more than any other celestial body we know of, the moon wears its gravity field on its sleeve," said Grail principal investigator Maria Zuber with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. "When we see a notable change in the gravity field, we can sync up this change with surface topography features such as craters, rilles or mountains."

In addition to mapping the moon's gravity, Ebb and Flow were also equipped with small student-controlled cameras. The MoonKAM program — which until her death in July was led by Sally Ride — allowed middle-school students to suggest and target areas on the moon to be imaged for their study.

Doing science until the end

Ebb and Flow conducted one final experiment before their mission ended. The two probes fired their main engines until their fuel tanks were empty to determine precisely the amount of propellant that remained.

The data from these last burns will help engineers validate fuel consumption computer models to improve predictions of the propellant needs for future missions.

"One thing is for sure — they are going down swinging," said Lehman. "Even during the last half of their last orbit, we're [doing] an engineering experiment that could help future missions operate more efficiently."

Because the exact amount of fuel that was remaining on each spacecraft was unknown, the Grail navigators and engineers designed the depletion burn to allow the probes to descend gradually for several hours and then skim the surface until the elevated terrain of the targeted mountain got in their way.

"We have had our share of challenges during this mission and always came through in flying colors, but nobody I know around here has ever flown into a moon mountain before," said Lehman. "It [is] a first for us, that's for sure."

Follow collectSPACE on Facebook and Twitter @collectSPACE and editor Robert Pearlman @robertpearlman. Copyright 2012 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.

In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.