The Universe Isn't a Fractal, Study Finds

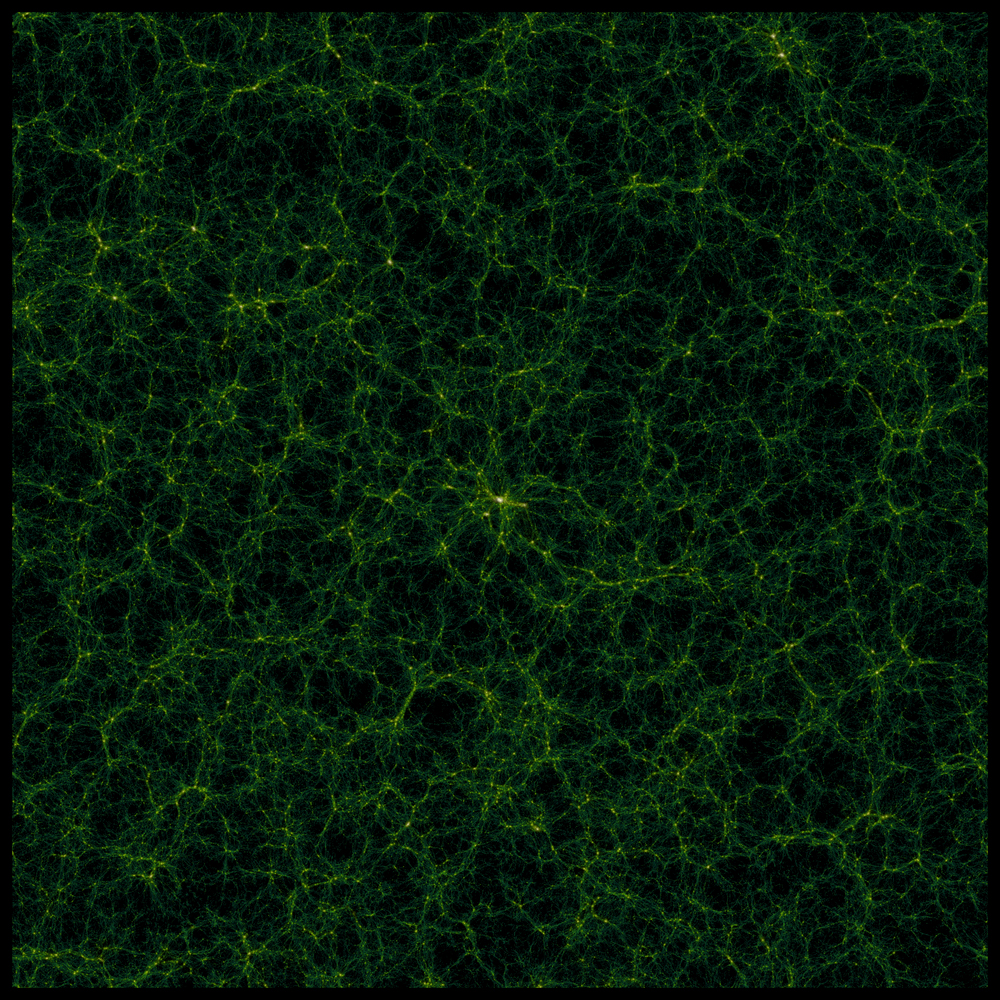

Stars crowd together into galaxies, galaxies assemble into clusters, and clusters amass to form superclusters. Astronomers, probing ever-larger volumes of the cosmos, have been surprised again and again to find matter clustering on ever-larger scales.

This Russian-nesting-doll-like distribution of matter has led them to wonder whether the universe is a fractal: a mathematical object that looks the same at any scale, whether you zoom in or out. If the fractal pattern continues no matter how far you zoom out, this would have profound implications for scientists' understanding of the universe. But now, a new astronomy survey refutes the notion.

The universe is fractal-like out to many distance scales, but at a certain point, the mathematical form breaks down. There are no more Russian nesting dolls — i.e., clumps of matter containing smaller clumps of matter — larger than 350 million light-years across.

The finding comes from Morag Scrimgeour at the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR) at the University of Western Australia in Perth and her colleagues. Using the Anglo-Australian Telescope, the researchers pinpointed the locations of 200,000 galaxies filling a cubic volume 3 billion light-years on a side. The survey, called the WiggleZ Dark Energy Survey, probed the structure of the universe at larger scales than any survey before it.

The researchers found that matter is distributed extremely evenly throughout the universe on extremely large distance scales, with little sign of fractal-like patterns. [5 Mind-Boggling Math Facts]

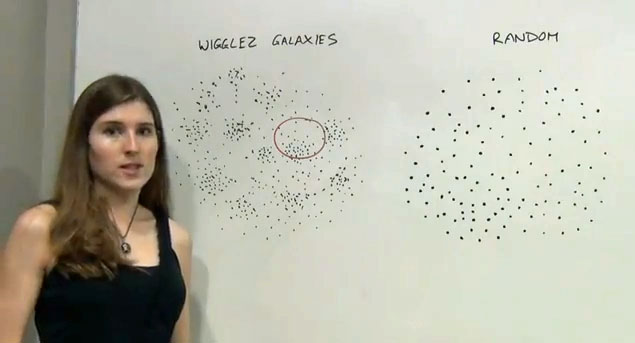

Scrimgeour explained the process that led to that conclusion. "We placed imaginary spheres around galaxies in the [WiggleZ survey] and counted the number of galaxies in the spheres," she explained in a video. "We wanted to compare this to a random homogeneous distribution" — one in which galaxies are spread evenly throughout space —"so we generated a random distribution of points and counted the number of random galaxies inside spheres of the same size."

The researchers then compared the number of WiggleZ galaxies inside the spheres with the number of random galaxies inside the similar spheres. When the spheres contained small volumes of space, WiggleZ galaxies were much more clumped together inside them than were the random galaxies. "But as we go to large spheres, this ratio tends to 1, which means we count the same number of Wigglez galaxies as random galaxies," Scrimgeour said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

And that means matter is evenly distributed throughout the universe at large distance scales, and thus that the universe isn't a fractal.

If it had been fractal-like, "it would mean our whole picture of the universe could be wrong," Scrimgeour said. According to the accepted history of the universe, there hasn't been enough time since the Big Bang 13.7 billion years ago for gravity to generate such large structures.

Furthermore, the assumption that matter is distributed evenly throughout the cosmos has allowed cosmologists to model the universe using Einstein's theory of general relativity, which relates the geometry of space-time to the matter spread uniformly within it.

Turns out, both assumptions are safe.

A paper detailing the findings will appear in a future issue of the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Journal.

This story was provided by Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site of SPACE.com. Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover or Life's Little Mysteries @llmysteries. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science and a contributor to Space.com from 2010 to 2012. She is now a senior writer and editor at Quanta Magazine, where she specializes in the physical sciences. Her writing has appeared in publications including Popular Science and Nature and has been included in The Best American Science and Nature Writing. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley.