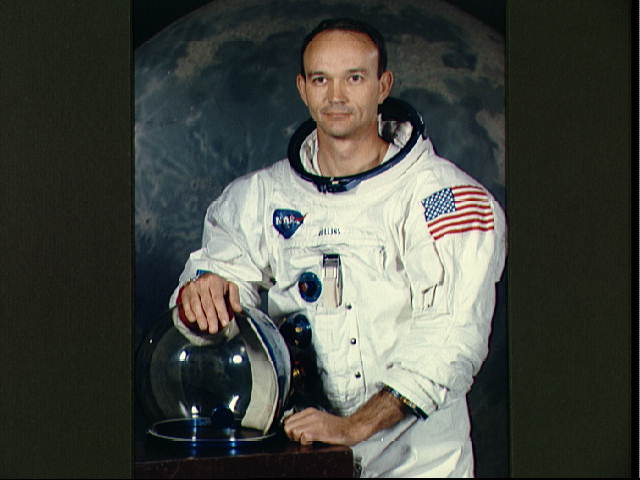

Michael Collins, Apollo 11 Command Module Pilot

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Editor's note: On April 28, 2021, Michael Collins' family announced that the Apollo 11 astronaut had died. After a battle with cancer, the family reported, Collins (90) passed away "peacefully, with his family by his side. Mike always faced the challenges of life with grace and humility, and faced this, his final challenge in the same way."

As Neil Armstrong and Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin took man's first steps on the moon, a third crew member orbited high above. Astronaut Michael Collins waited in the command module while his fellow astronauts spent more than 21 hours on the lunar surface. He was the first astronaut to orbit the far side of the moon alone; on each pass on the far side, he was cut off from human contact on Earth because there were no satellites available to relay his communications back to Earth. Here is a brief look at the life of the least-known member of the Apollo 11 crew.

Preparing for space

The son of a U.S. Army major general, Michael Collins was born October 31, 1930, in Rome, Italy, where his father was stationed. The family later moved to the United States, and after high school, Collins enrolled at West Point Military Academy. After receiving a bachelor of science degree in 1952, Collins joined the Air Force and finished flight training in Columbus, Mississippi.

"His performance earned him a position on the advanced day fighter training team at Nellis Air Force Base, flying F-86 Sabres. This was followed by an assignment to the 21st Fighter-Bomber Wing at the George Air Force Base, where he learned how to deliver nuclear weapons. He also served as an experimental flight test officer at Edwards Air Force Base in California, testing jet fighters," History.com wrote of Collins' Air Force experience.

In 1962, after watching John Glenn's historic flight, Collins applied to become an astronaut. At that time, NASA only had seven astronauts (selected for its Mercury program) and needed more for the two-person Gemini spacecraft. Collins did not pass the astronaut selection that time, so he picked up more advanced flight training experience at the Air Force Aerospace Research Pilot School. He did make it into the third group of astronauts in 1963, who were hired for the Gemini Earth-orbiting missions (which flew crews between 1965 and 1966) and the Apollo program (which is most famous for its moon missions, but flew human missions to both Earth and the moon between 1968 and 1972).

'Absolutely isolated'

Collins served as a pilot on Gemini 10, which launched July 18, 1966. The 16th crewed spacecraft to circle Earth, the mission's purpose was to conduct rendezvous and docking tests with two target vehicles, a booster launched earlier that day and a defunct booster left over from Gemini 8. During the mission, Collins performed two spacewalks, spending over an hour outside of the ship and becoming the first person to meet another craft in orbit.

Spacewalks were among NASA's major goals in doing the Gemini program, which was intended to prepare the agency and its astronauts for moon missions. Gemini also examined how to do rendezvous (meeting up) and docking between spacecraft, which was a complicated affair given the simple computers of the 1960s. dAs is usual among astronauts, Collins also served as a constant support for other missions. For example, he played a key role in Mission Control during Apollo 8, the first human spacecraft to orbit the moon in 1968. He served as the astronaut responsible for communicating with the crew from Mission Control.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

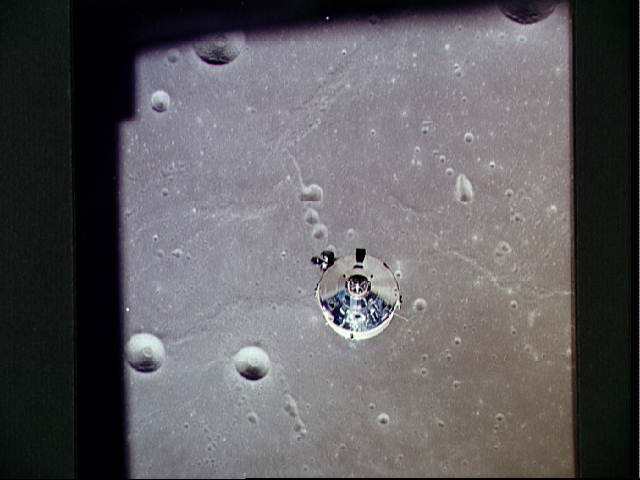

For his second and final mission in space, Collins served as command module pilot for Apollo 11. Each Apollo mission had two spacecraft — a command module ("Columbia") and a lunar module ("Eagle"). One astronaut was supposed to remain behind in the command module while the other two astronauts flew to the moon and back in the lunar module. So while fellow astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin traveled to the surface of the moon in the lunar module, Collins worked alone in the command module for 21.5 hours, running systems checks, performing moon observations, and communicating with Mission Control when he could. As the command module drifted behind the moon, however, cutting off his communication with Earth, he wrote:

"I am alone now, truly alone, and absolutely isolated from any known life. I am it. If a count were taken, the score would be three billion plus two over on the other side of the moon, and one plus God knows what on this side."

Collins also was concerned that the lunar module had never been fired on the moon. The astronauts knew there was a chance that Armstrong and Aldrin could remain stranded on the lunar surface or, if the engine didn't burn long enough, be lost in space, leaving Collins the sole survivor of the historic mission. President Nixon had even prepared a speech in case of such a tragedy.

But the engine on the lunar module worked flawlessly. At 1:54 p.m. EDT, the Eagle blasted back up to the command module. Collins performed the necessary docking maneuvers with the lunar module. Armstrong and Aldrin rejoined him, and the three astronauts returned home safely.

After NASA

Collins spent a total of 266 hours — over 11 days — in space. He left NASA in 1970 and served as director of the National Air & Space Museum in Washington, D.C., for eight years before entering the private sector. He and his wife, Patricia, have three grown children.

In a press release in 2009, for the 40th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission, Collins said he was happy with his seat on the Apollo 11 mission, calling it "an honor" to serve. In his notes while circling the moon alone, he wrote, "I feel very much a part of what is taking place on the lunar surface."

In a 2016 interview with Air&Space Magazine, Collins — then 85 years old — said he fished, painted watercolors, and performed one mini-triathlon a year. He said he had no plans to write any more books, as after four completed books, "I've said about everything I want to say."

Collins talked about his experiences with moon hoaxers (those who think the moon landing was faked), and said he does continue to follow the space program, but only in the casual sense. That said, he said he still is hopeful that humans will go to Mars one day. "My friend Neil Armstrong thought it was a good idea to have a stop-off point at the moon, and he's a lot better engineer than I. So I respect the people who want a lunar base, maybe on the south pole or over on the back side where electronically it's a quiet zone. But not me. Mars – let's go," Collins said.

Additional reporting by Elizabeth Howell, Space.com Contributor.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky