Weather Window Wonder: Five-Day Forecasts More Accurate

A new instrument for measuring water vapor in the atmosphere will improve the accuracy of the timing of medium-range weather forecasts by as much as six hours, scientists said Wednesday.

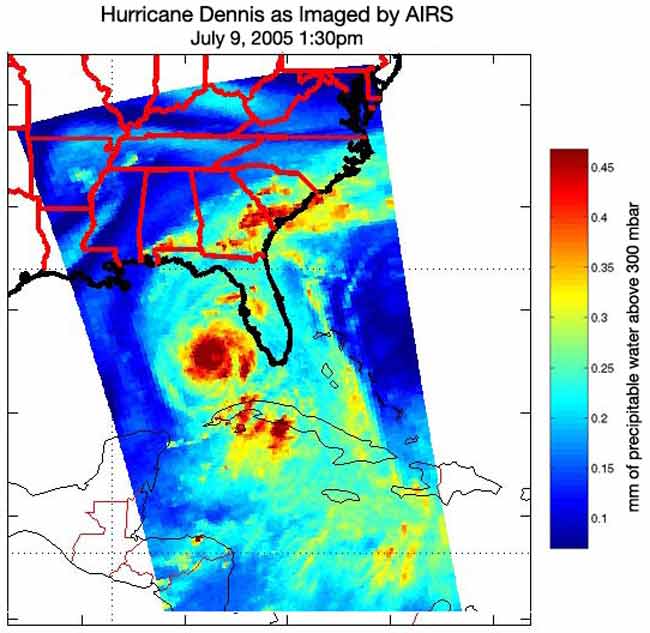

Researchers used experimental data from the Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument on NASA's Aqua satellite to make the predictions. The instrument takes 3-dimensional pictures of atmospheric temperatures, water vapor, and trace gases.

With these data, scientists improved the accuracy of medium-range weather predictions, generally called "your five" or "six day forecast" on local news programs, by up to six hours. This represents a four-percent increase over previous timing accuracy.

"What you'll see is a small improvement in the quality of your forecast," Stephen Lord, director of the Environmental Modeling Center at the National Center for Environmental Prediction, told SPACE.com. "Before, rain would be forecasted for two days out. Now we can change that to one and three quarter or two and a quarter days."

Based on the success of the experiments, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) National Weather Service has officially incorporated AIRS data in its operational weather forecasts worldwide.

The huge amount of data that AIRS takes in makes these improved forecasts possible. AIRS scans the atmosphere using over 2,300 infrared and four visible light channels. This information--mostly about water vapor and temperature--is lumped together and compared to computer forecast models.

"What AIRS brings to the table is just a lot more information in the spectra," said JPL meteorologist Eric Fetzer. "This translates into a lot more information about the structure of the atmosphere."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Aqua satellite--orbiting at 705 kilometers (438 miles)--is sun synchronous, so it makes two sets of observations per day for any given location.

"This particular model and system covers the entire globe," Lord said. "It will provide a better forecast pretty much everywhere, statistically at least. If you look at the average statistics over the globe over a period of a month, you'll see that on average forecasts are more accurate than before we implemented these changes."

This work is the most recent collaboration between scientists at NASA and the NOAA. As the NOAA tracks hurricanes and delivers forecasts and warnings, NASA's supercomputer Columbia crunches data to provide up-to-date five day forecasts.

"Satellite data, like AIRS provides, is a vital link for NOAA to continuously take the pulse of the planet," said retired U.S. Navy Vice Admiral and NOAA administrator Conrad C. Lautenbacher, Jr.

AIRS tracked July's Hurricane Dennis, measuring the amount of water in the storm. Hurricane intensity, and whether it is getting stronger or weaker, can be estimated by measuring the amount of rainfall in the storm.

While this improvement to weather forecasts may not seem like much, as each stage of research moves forward, forecasts will get more and more accurate.

"Each stage puts in better science. NASA improves better resolution. And we test over months to make sure the results are actually improvements," Lord said. "In order to provide the best services to the nation, we have to do an enormous amount of testing."

And AIRS has not even been used to its full capacity yet.

"They're only using one percent of the information - there's a lot more information in the observations than what's currently used," Fetzer said. "But that's what research is all about - figuring out how to use that remaining 99 percent."