European Probe Finishes Mapping Big Bang's Echo

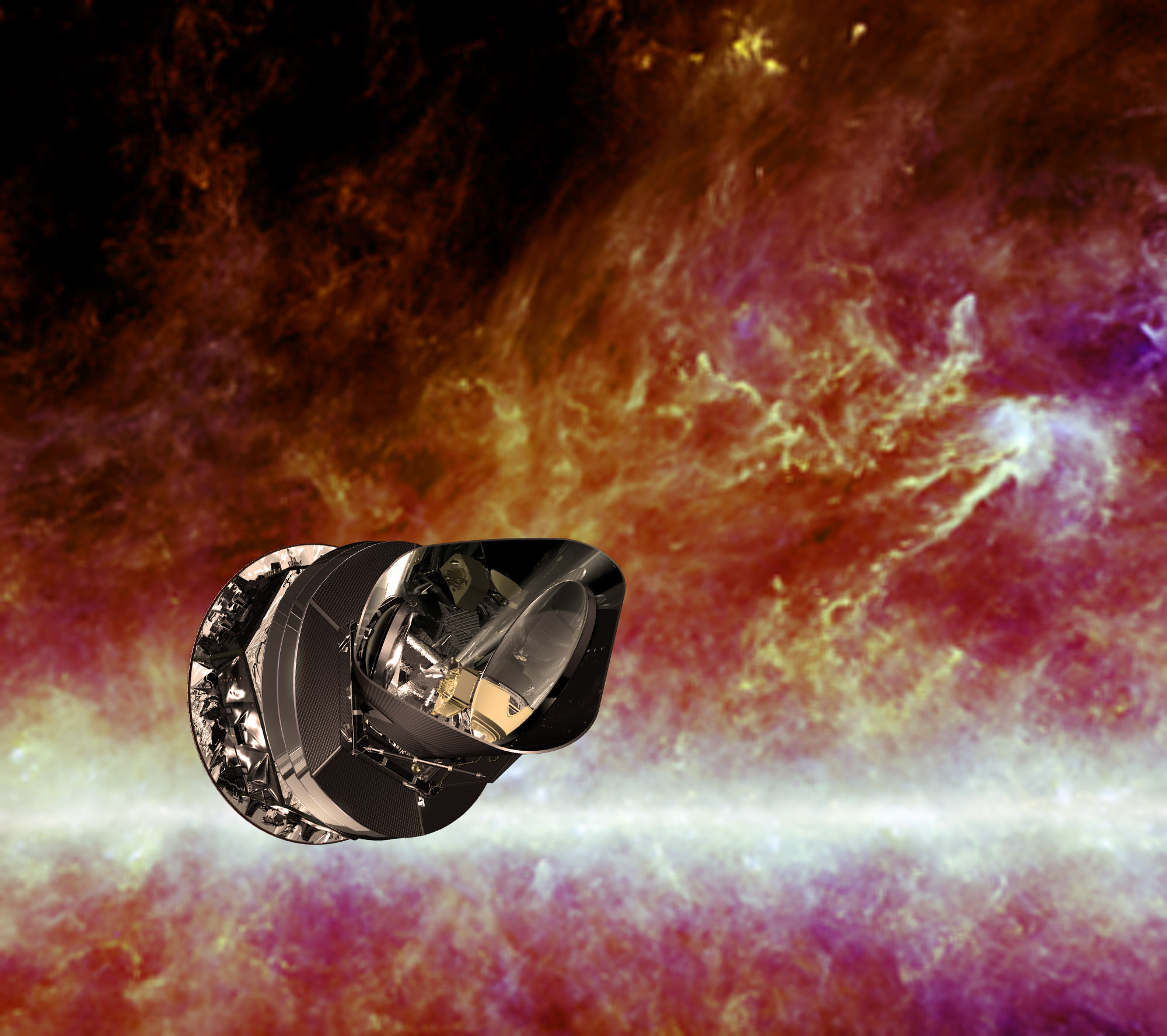

A European space observatory that's surveying the light left over from the birth of the universe has wrapped up a big part of its mission.

The High Frequency Instrument (HFI), one of two sensors aboard the European Space Agency's Planck spacecraft, ran out of its vital coolant as planned Saturday (Jan. 14), ESA officials announced. Without the coolant, the instrument can't detect the faint cosmic microwave background (CMB) — the remnant radiation left over from the Big Bang 13.7 billion years ago.

The instrument did its job, researchers said, completing five full-sky surveys of the CMB since the spacecraft's May 2009 launch. Planck's mission called for a minimum of two such surveys, researchers said.

"Planck has been a wonderful mission; spacecraft and instruments have been performing outstandingly well, creating a treasure trove of scientific data for us to work with," said Jan Tauber, ESA's Planck project scientist, in a statement. [Photos: Planck Sees Big Bang Relics]

Surveying the universe's early light

The CMB is an "echo" of the Big Bang, the dramatic event that gave birth to our universe.

This radiation is a remnant of the first light emitted after the universe had cooled enough to allow light to travel freely. By studying patterns imprinted in the CMB today, scientists hope to better understand the Big Bang and the very early universe.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Planck has been measuring these patterns by surveying the whole sky with its two instruments, the HFI and the Low Frequency Instrument (LFI). These sensors require incredibly cold temperatures to detect the faint CMB, so Planck cooled them down to minus 459.49 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 273.05 Celsius) — just 0.1 degree Celsius above absolute zero, the coldest temperature theoretically possible in our universe.

While HFI's work is done, LFI will continue surveying the sky for much of 2012, gathering calibration data that will help improve Planck's final results. Researchers said they're happy with how long HFI lasted.

"This gives us even better data than we were expecting from the mission," said HFI principal investigator Jean-Loup Puget of the Université Paris Sud in Orsay, France.

Results coming next year

In addition to primordial microwaves from the Big Bang, Planck also sees emissions from cold dust scattered throughout the universe.

Researchers have already announced some initial results from the Planck mission. These include a catalog of galaxy clusters in the distant universe, many of which had not been seen before, and the best measurement yet of an infrared background covering the sky, researchers said.

This infrared background was likely produced by stars forming in the early universe, showing that some of the first galaxies created stars at a rate 1,000 times greater than our own Milky Way galaxy does today.

However, the first Planck findings about the Big Bang and CMB are not expected for another year, researchers said. More time is needed to tease the faint and subtle CMB signals out from a sea of other emissions.

Planck's results could shed a great deal of light on the Big Bang and its aftermath, an ancient epoch that is well-understood only in its basic outlines.

"Planck's data will kill off whole families of models; we just don't know which ones yet," Puget said.

The Big Bang data will be released in two stages. The first 15 1/2-months' worth of observations will be published in early 2013, and the full data release from the entire mission will come a year after that, researchers said.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Space.com is the premier source of space exploration, innovation and astronomy news, chronicling (and celebrating) humanity's ongoing expansion across the final frontier. Originally founded in 1999, Space.com is, and always has been, the passion of writers and editors who are space fans and also trained journalists. Our current news team consists of Editor-in-Chief Tariq Malik; Editor Hanneke Weitering, Senior Space Writer Mike Wall; Senior Writer Meghan Bartels; Senior Writer Chelsea Gohd, Senior Writer Tereza Pultarova and Staff Writer Alexander Cox, focusing on e-commerce. Senior Producer Steve Spaleta oversees our space videos, with Diana Whitcroft as our Social Media Editor.