Strange Crystals Reveal Rock to be Ancient Meteorite

A rock made of a type of crystal never before seen outside a laboratory is most likely a meteorite from the early days of the solar system, geologists say.

Two years after identifying the Russian rock's unusual composition, a team of scientists thinks it has nailed down its origin. The researchers say it is a quasicrystal formed under conditions far more likely in space than inside the Earth, and that its chemical composition of metallic copper and aluminum resembles what is found in so-called carbonaceous chondrites – the primitive meteorites that scientists think were remnants shed from the original building blocks of planets.

Crystals are symmetrical, neatly ordered patterns of atoms that repeat themselves regularly. They are found commonly in nature in different types of rock.

Thirty years ago, through experiments changing the structure of crystals, laboratories began producing quasicrystals, a strange arrangement of atoms that repeats with two different frequencies rather than one. Rather than a simple ratio of, say, 2:1, the ratio of atoms in a quasicrystal is based on an irrational number, such as the square root of 2:1. (This year's Nobel Prize in Chemistry honored Dan Shechtman for his 1982 discovery of quasicrystals.)

'A disharmony in space'

Researcher Paul Steinhardt of Princeton University describes such a bizarre arrangement as "a disharmony in space."

"Any symmetry thought to be forbidden is possible for quasicrystals," he told SPACE.com in an email.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The most familiar of such arrays is found on the face of a soccer ball, composed of 20 hexagonal faces with 12 pentagons interspaced.

Synthetic quasicrystals are used to strengthen steel and aluminum, or to create a Teflon-like material that is harder and nearly as slippery as the metals.

"At present, we have a limited menu of quasicrystals," Steinhardt said. "One of the reasons for conducting a search of natural quasicrystals is to see if nature found ones that have not yet been discovered synthetically by trial and error."

Quasicrystals in nature

In 1998, Steinhardt and his team began a systematic search for a naturally occurring quasicrystal, scanning databases of known crystals for patterns that resembled those of quasicrystals.

Each candidate sample was sliced and diced with X-ray and electron diffraction imaging techniques, Steinhardt said.

For eight years the team sought in vain. Then, in 2007, Luca Bindi of Italy's University of Florence offered his collection of minerals to the group for examination.

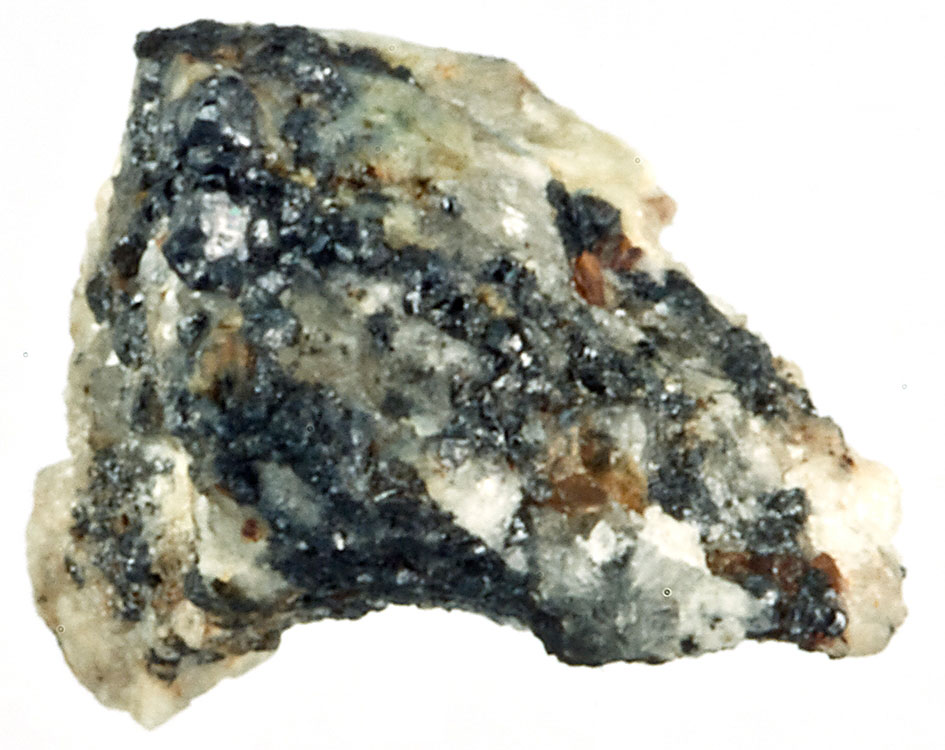

One of the rocks, which had been found in the Koryak Mountains in eastern Russia, was a perfect match. [5 Reasons to Care About Asteroids]

With the first naturally occurring quasicrystal finally found, the next step was to determine its origins.

Extraterrestrial origins

Bindi led a team of researchers in analyzing the quasicrystal rock's structure, which revealed that the rock must have had an extraterrestrial birth. The scientists reported their findings in the Jan. 2 issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.

Inside meteorites, which have been exposed to the environment of space, the ratios of oxygen atoms and their variations, called isotopes, are fixed by intense space radiation and cosmic rays.

But the interior of Earth shields elements from these rays, allowing materials inside Earth-bound rocks to mix and changing these ratios.

An examination of the oxygen isotopes in the Russian rock indicated that it must have originated in the early solar system.

"Now that we know that quasicrystals formed in the early solar system, we need to understand exactly how," Steinhardt said. "More material and more tests are needed to understand how nature has managed to accomplish the feat."

Wider samples

At the moment, however, the Koryak sample is the only known naturally occurring quasicrystal.

"My hope is that many more mineralogists, petrologists and meteorite experts will begin searching for natural quasicrystals as well," Steinhardt said.

Though the Koryak sample came from space, Steinhardt said that he doesn't believe that all quasicrystals necessarily do.

"There is no reason to believe that ours is the only natural quasicrystal, or that all quasicrystals are extraterrestrial," he said.

A wider sample could provide greater clues to how these strange crystals were created.

Old instead of odd

That such a crystal formed so long ago changes how scientists view quasicrystals.

"Until now, quasicrystals were thought to be oddballs, and one of the newest materials formed," Steinhardt said. "Now we know that is completely wrong. Quasicrystals are one of the first minerals to have formed in the solar system — in the top 250 — long before most of the common minerals found on Earth."

Their formation is probably not unique to the environment around the sun. Instead, quasicrystals may exist throughout the Milky Way and other galaxies.

"They are perhaps the most common mineral to have formed in the universe," Steinhardt speculated.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcomand on Facebook.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky