Five-Beamed Mega-Laser to Help Capture Better Space Photos

To help take extra sharp images of space, a telescope in South America is firing a mega-laser – one made up of five beams – into the night sky.

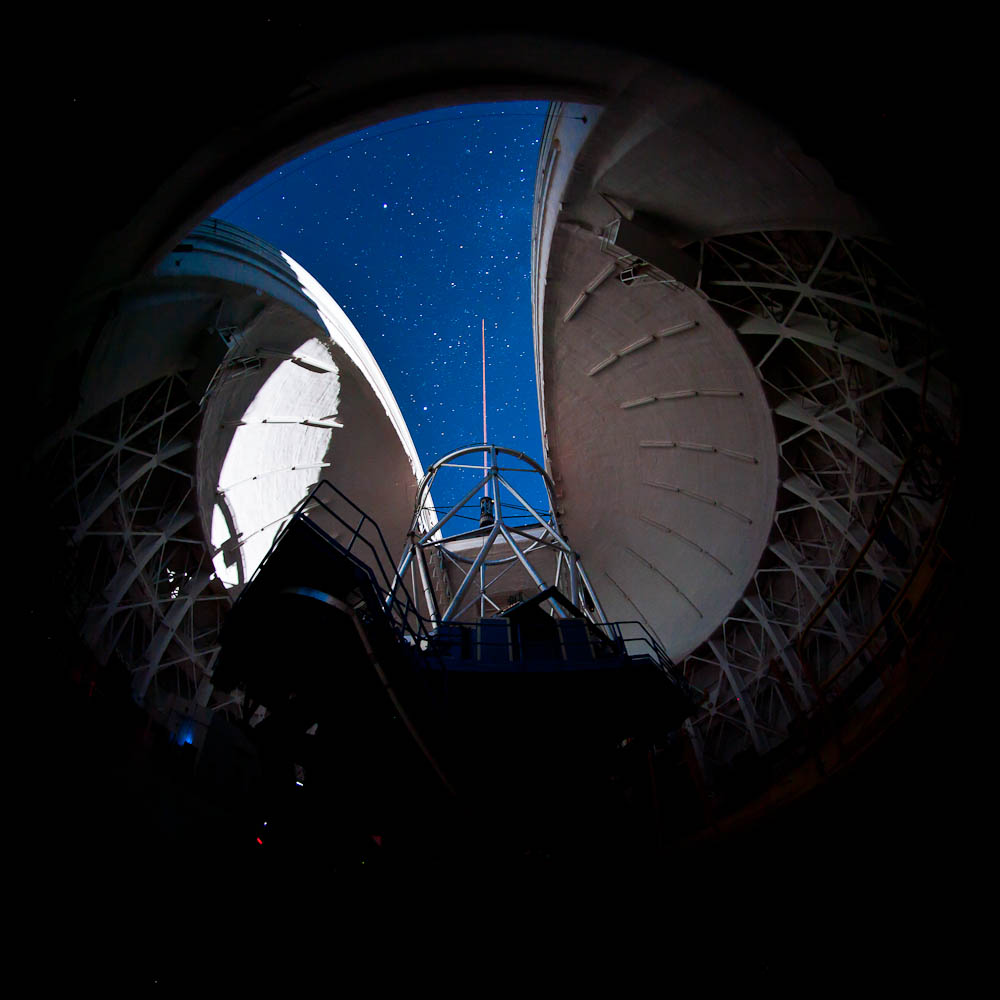

The sodium laser "constellation" – as scientists call it – is part of a telescope at the Gemini South Observatory in Chile and is the cornerstone for a next-generation adaptive optics system. Photos of the laser in action reveal it as a thick, bright yellow beam of light cutting through the night sky.

Adaptive optics is a technique used by telescopes to filter out the hazy interference of Earth's atmosphere during astronomical observations.

Computers analyze the light from a natural or artificial guide star, and then use that light as a baseline to determine the blurring effects of the atmosphere. Hundreds of actuators can then be used to warp the surface of the telescope's mirrors thousands of times per second to cancel out any blurry effects.

The constellation of five lasers used at the Gemini South telescope serves as the artificial guide star for its next-generation adaptive optics system, called the Gemini Multi-Conjugate Adaptive Optics (MCAO) System – or GeMS. It consists of a single 50-watt laser that is then split into five individual beams that create a five-point "star" grouping when they're fired 56 miles (90 kilometers) into the sky.

Computers use the lasers to build a real-time, three-dimensional view of the atmosphere and use that data to change the shape of the telescope's mirror to cancel out blurring effects about 1,000 times per second.

Astronomers switched the laser system on for the first time on Jan. 22 while a photographer documented the event with a digital camera equipped with a 500 millimeter lens.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

“The Gemini team has been working very hard for a very long time to get to this point and when I saw those 5 stars shining on the sky through my viewer it gave me goose bumps,” said Maxime Boccas, head of the Gemini Observatory’s Optical Systems Group, who took some of the photos.

The GeMS system's laser guide stars are not actually visible to the unaided eye. To see them, observers would need a telescope or powerful binoculars, Gemini Observatory officials said. At ground level, the laser is visible to the unaided eye due to scattering effects, they added.

Those scattering effects allowed photographers to snap dazzling photos of the laser constellation at work.

“This amazing picture illustrates the culmination of a laser development program that started about 10 years ago,” said Gemini Observatory’s senior laser engineer Céline d’Orgeville.

The new laser system is expected to undergo a series of commissioning tests before it begins science observations in 2012. The system is expected to generate ultra-clear views of distant galaxies, newborn stars and other cosmic objects.

Tariq is the award-winning Editor-in-Chief of Space.com and joined the team in 2001. He covers human spaceflight, as well as skywatching and entertainment. He became Space.com's Editor-in-Chief in 2019. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. He's a recipient of the 2022 Harry Kolcum Award for excellence in space reporting and the 2025 Space Pioneer Award from the National Space Society. He is an Eagle Scout and Space Camp alum with journalism degrees from the USC and NYU. You can find Tariq at Space.com and as the co-host to the This Week In Space podcast on the TWiT network. To see his latest project, you can follow Tariq on Twitter @tariqjmalik.