How many stars are in the universe?

Can we estimate the total number of stars?

Looking up into the night sky, you might wonder just how many stars are in the universe. It's challenging enough for an amateur astronomer to count the number of naked-eye stars that are visible and, with bigger telescopes, more stars become visible, making counting a lengthy process. So how do astronomers figure out how many stars are in the universe?

The first sticky part is trying to define what "universe" means, said David Kornreich, an assistant professor at Ithaca College in New York State. He was the founder of the "Ask An Astronomer" service at Cornell University.

"I don't know [the answer] because I don't know if the universe is infinitely large or not," he said. The observable universe appears to go back in time by about 13.8 billion years, but beyond what we could see there could be much, much more. Some astronomers also think that we may live in a "multiverse" where there would be other universes like ours contained in some sort of larger entity.

The simplest answer may be to estimate the number of stars in a typical galaxy, and then multiply that by the estimated number of galaxies in the universe, according to the European Space Agency (ESA). But even that is tricky, as some galaxies shine better in visible or some in infrared, for example. There also are estimation hurdles that must be overcome.

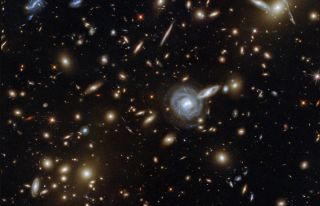

In October 2016, deep-field images from the Hubble Space Telescope suggested that there are about 2 trillion galaxies in the observable universe, or about 10 times more galaxies than previously suggested, according to the journal Nature. In an email with Live Science, lead author Christopher Conselice, a professor of astrophysics at the University of Nottingham in the United Kingdom, said there were about 100 million stars in the average galaxy.

Telescopes may not be able to view all the stars in a galaxy, however. A 2008 estimate by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (which catalogs all the observable objects in a third of the sky) found about 48 million stars, roughly half of what astronomers expected to see. A star like our own sun may not even show up in such a catalog. So, many astronomers estimate the number of stars in a galaxy based on its mass — which has its own difficulties, since dark matter and galactic rotation must be filtered out before making an estimate.

Missions such as the Gaia mission, a European Space Agency space probe that launched in 2013, may provide further answers. Gaia aims to precisely map about 1 billion stars in the Milky Way. It builds on the previous Hipparchus mission, which precisely located 100,000 stars and also mapped 1 million stars to a lesser precision. Data from the mission is due to be released in June 2022, according to ESA.

"Gaia will monitor each of its 1 billion target stars 70 times during a five-year period, precisely charting their positions, distances, movements and changes in brightness," ESA said on its website. "Combined, these measurements will build an unprecedented picture of the structure and evolution of our galaxy. Thanks to missions like these, we are one step closer to providing a more reliable estimate to that question asked so often: 'How many stars are there in the universe?'"

Observable universe

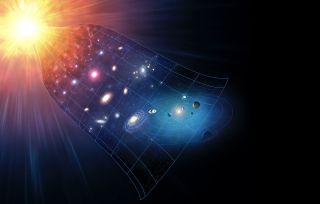

Even if we narrow down the definition to the "observable" universe — what we can see — estimating the number of stars within it requires knowing just how big the universe is. The first complication is that the universe itself is expanding, and the second complication is that space-time can curve.

To take a simple example, light from the objects farthest away from us would take approximately 13.8 billion light-years to travel to Earth, taking into account that the very youngest objects would be shrouded because light couldn't carry in the early universe. So the radius of the observable universe should be 13.8 billion light-years since light only has that long to reach us.

Or should it? "It's a logical way to define distance, but not how a relativist defines distance," Kornreich said. A relativist would use a device such as a meter stick, measuring the distance along that device and then extending it as long as needed.

This produces a different answer, which some sources define as 48 billion light-years in radius. Sources vary on this number, however. That's because space-time can curve. As the observer does the measurement with the meter sticks, light travels at the same time and influences the measurements.

Galaxy observations

It's easier to count stars when they are inside galaxies, since that's where they tend to cluster, according to the Harvard and Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. To even begin to estimate the number of stars, then you would need to estimate the number of galaxies and come up with some sort of an average.

Some estimates peg the Milky Way's star mass as having 100 billion "solar masses," or 100 billion times the mass of the sun. Averaging out the types of stars within our galaxy, this would produce an answer of about 100 billion stars in the galaxy. This is subject to change, however, depending on how many stars are bigger and smaller than our own sun. Also, other estimates say the Milky Way could have 200 billion stars or more.

The number of galaxies is an astonishing number, however, as shown by some imaging experiments performed by the Hubble Space Telescope. Several times over the years, the telescope has pointed a detector at a tiny spot in the sky to count galaxies, performing the work again after the telescope was upgraded by astronauts during the shuttle era.

A 1995 exposure of a small spot in Ursa Major revealed about 3,000 faint galaxies. In 2003-4, using upgraded instruments, scientists looked at a smaller spot in the constellation Fornax and found 10,000 galaxies. An even more detailed investigation in Fornax in 2012, with even better instruments, showed about 5,500 galaxies.

Kornreich used a very rough estimate of 10 trillion galaxies in the universe. Multiplying that by the Milky Way's estimated 100 billion stars results in a large number indeed: 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 stars, or a "1" with 24 zeros after it (1 septillion in the American numbering system; 1 quadrillion in the European system). Kornreich emphasized that number is likely a gross underestimation, as more detailed looks at the universe will show even more galaxies.

Additional resources

Read more about estimating the number of stars in the Milky Way in this article by NASA. Additionally, you can see some of the best images of stars taken by Hubble in ESA's image archive.

Bibliography

"Universe has ten times more galaxies than researchers thought". Nature (2016). https://www.nature.com/articles/nature.2016.20809.pdf?origin=ppub

"The Sloan Digital Sky Survey reveals a new Milky Way neighbor". SDSS (2006). https://classic.sdss.org/news/releases/20060109.virgooverdensity.html

"Star Clusters". Harvard and Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. https://pweb.cfa.harvard.edu/research/topic/star-clusters

"Oases in the Dark: Galaxies as probes of the Cosmos". Utah State University (2007). https://digitalcommons.usu.edu

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., is a staff writer in the spaceflight channel since 2022 covering diversity, education and gaming as well. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years before joining full-time. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House and Office of the Vice-President of the United States, an exclusive conversation with aspiring space tourist (and NSYNC bassist) Lance Bass, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?", is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams. Elizabeth holds a Ph.D. and M.Sc. in Space Studies from the University of North Dakota, a Bachelor of Journalism from Canada's Carleton University and a Bachelor of History from Canada's Athabasca University. Elizabeth is also a post-secondary instructor in communications and science at several institutions since 2015; her experience includes developing and teaching an astronomy course at Canada's Algonquin College (with Indigenous content as well) to more than 1,000 students since 2020. Elizabeth first got interested in space after watching the movie Apollo 13 in 1996, and still wants to be an astronaut someday. Mastodon: https://qoto.org/@howellspace