NASA Maps Out Goals for Potential Landing On Jupiter's Moon Europa

The top priority of a robotic lander mission to Jupiter's potentially life-supporting moon Europa should be investigating the composition and chemistry of its subsurface ocean, scientists say.

Such a mission should also aim to determine the thickness and dynamics of the moon's ice shell and characterize the surface geology of Europa in detail, a NASA-appointed "science definition team" reports in a new study in the journal Astrobiology.

"If one day humans send a robotic lander to the surface of Europa, we need to know what to look for and what tools it should carry," study lead author Robert Pappalardo, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., said in a statement. [Photos: Europa, Mysterious Icy Moon of Jupiter]

"There is still a lot of preparation that is needed before we could land on Europa, but studies like these will help us focus on the technologies required to get us there, and on the data needed to help us scout out possible landing locations," Pappalardo added.

Pappalardo and his colleagues further recommend that any Europa lander be capable of drilling up to 4 inches (10 centimeters) into the moon's surface ice. Collecting underground samples from different depths would help scientists figure out the ocean's composition and determine how it is affected by the high levels of radiation that bombard the icy moon, they write.

The team also suggests a model payload for a potential Europa lander consisting of seven scientific instruments: a mass spectrometer, Raman spectrometer, magnetometer, multiband seismometer package, site imaging system, microscopic imager and reconnaissance imager.

"This model payload is meant as a proof of concept representing the range of possible instruments that could be used to investigate Europa in situ," the scientists write in the study, stressing that thorough reconnaissance of the moon would be required to pick out a safe and suitable landing site.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

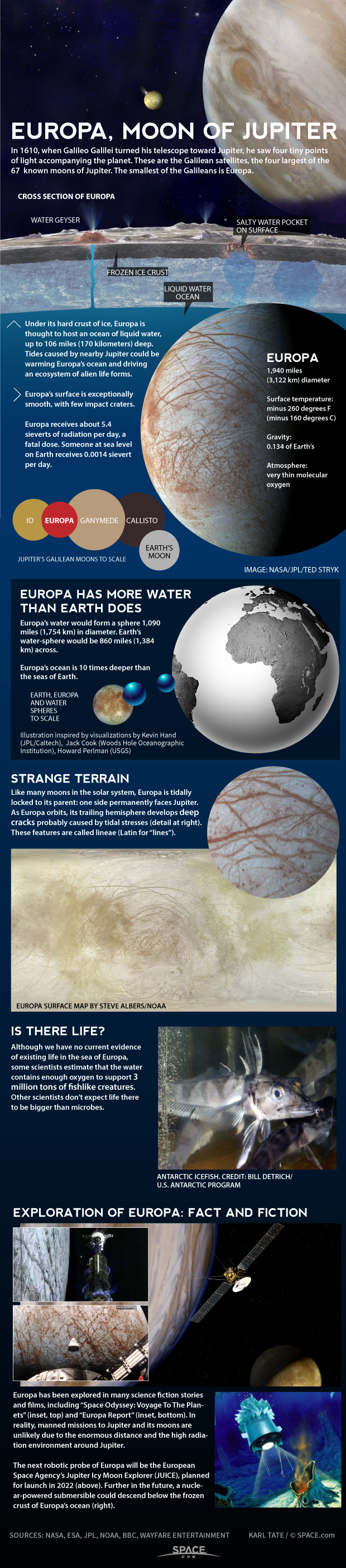

Astrobiologists would love to drop a lander onto Europa, a 1,900-mile-wide (3,100 kilometers) moon that is regarded as perhaps the most likely candidate in our solar system to host life beyond Earth. But no such mission is yet on the books at NASA, or anywhere else.

The European Space Agency is leading a mission called JUICE (short for JUpiter ICy moons Explorer), which aims to launch a probe toward the solar system's largest planet in 2022.

The JUICE spacecraft would reach the Jovian system in 2030 and spend at least three years studying Jupiter, Europa and its fellow satellites Callisto and Ganymede. But the probe would not land on any of these worlds.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.