Jupiter's massive gravity kicked strange Ceres into the asteroid belt

Ceres always seemed rather out of place.

A new computer simulation suggests that dwarf planet Ceres may have been flung by the gravity of gas giant Jupiter toward the sun during the volatile era of planet formation 4.5 billion years ago.

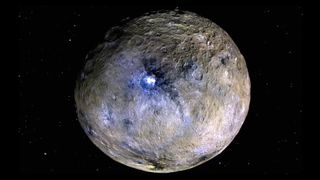

There has always been something out of place about Ceres. At 600 miles (1,000 kilometers) wide, Ceres is by far the largest body in the asteroid belt, the region between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter where space rocks (most of them only tens or hundreds of meters in size and oddly shaped) gather.

Round like a planet, Ceres also contains some odd chemical compounds, such as ammonia, that are not present in its neighbors. Ceres' strange nature has long led scientists to believe that the dwarf planet is an intruder in the asteroid belt. A new simulation led by researchers from Sao Paulo State University in Brazil has now revealed a mechanism that may have displaced Ceres from its original birthplace in the distant past.

Related: Biggest mysteries of the dwarf planet Ceres

"In our article, we propose a scenario to explain why Ceres is so different from neighboring asteroids," Rafael Ribeiro de Sousa, a physics professor at Sao Paulo State University in Brazil and lead author of the new study told Universe Today. "In this scenario, Ceres began forming in an orbit well beyond Saturn, where ammonia was abundant. During the giant planet growth stage, it was pulled into the asteroid belt as a migrant from the outer solar system and survived for 4.5 billion years until now."

While unseen in ordinary space rocks, ammonia is common in comets, the dirty snowballs that originate in the much colder outer reaches of the solar system and come to visit us from time to time, providing spectacular views to astronomers with their stunning tails of evaporating gas.

Cometary tails appear as comets arrive closer to the sun where temperatures are high enough to melt their ice. Something similar is going on with Ceres, which is the only object in the asteroid belt to have a thin atmosphere of evaporating water and ammonia ice, according to Universe Today.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But if Ceres formed where comets form, how exactly did it end up in the asteroid belt?

The key, the study suggests, is the powerful gravity of the gas giant Jupiter, which emerged as a major force during the formation of the solar system 4.5 billions of years ago.

"Our simulations showed that the giant planet formation stage was highly turbulent, with huge collisions between the precursors of Uranus and Neptune, ejection of planets out of the solar system, and even invasion of the inner region by planets with masses greater than three times Earth's mass," Ribeiro de Sousa said. "In addition, the strong gravitational disturbance scattered objects similar to Ceres everywhere. Some may well have reached the region of the asteroid belt and acquired stable orbits capable of surviving other events."

During this cosmic billiard period, there may have been up to 3,600 mini-planets the size of Ceres bouncing around the protoplanetary disk of dust and gas from which planets emerged.

"With this number of objects, our model showed that one of them could have been transported and captured in the asteroid belt, in an orbit very similar to Ceres's current orbit," Ribeiro de Sousa said.

The study is not the first to have come up with such conclusions, according to Universe Today, but it contributes to the growing understanding of the early violent years of the solar system's formation.

"Our scenario enabled us to confirm the number and explain Ceres' orbital and chemical properties," Ribeiro de Sousa said.

Astronomers know quite a lot about Ceres thanks to NASA's Dawn mission, which orbited first the dwarf planet, then asteroid Vesta, the second largest object in the asteroid belt, in the 2010s. The Dawn spacecraft ran out of fuel in 2018 while in orbit around Ceres.

The study was published in the journal Icarus on May 17.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.